Interview Coming Up at Conversations LIVE!

On Monday, July 6, I'll be interviewed by host Cyrus A. Webb on Conversations LIVE!, Blog Talk Radio, at 1 p.m. Eastern Time. The show is sponsored by The Write Stuff Literacy Campaign.

Back on May 28, I was interviewed by Mark Eller, host of Chronicles, also on BTR. That show is now available as a podcast here and elsewhere.

As someone on dial-up, I know how it feels to wait through a download. With that in mind -- and to provide links to websites Mark and I mentioned, along with some accompanying photos -- I've transcribed the show, cleaning up some word repetitions and the like. Click below for the transcript.

Chronicles, May 28, 2009

Mark Eller: Hello, everybody. This is Chronicles, and I am your host, Mark Eller. And we are here today to speak with Elissa -- how do you pronounce your last name, Elissa?

Elissa Malcohn: It's [El-EE-sa Mal-KOHN].

Eller: Elissa Malcohn. Thank you. I wasn't really sure how to pronounce that.

Malcohn: Oh, that goes back a long ways. People have been mispronouncing my name for decades. That's okay.

Eller: How are you doing today, Elissa?

Malcohn: I'm doing fine. I'd like to thank you very much for having me on the show.

Eller: I would like to thank you very much for coming on to the show. It's an honor to have you here, because, to tell you the truth, I was looking over your bio, and you make me feel a little bit tired. I have a habit with that with my guests so far. They all make me feel a little bit tired and somewhat unmotivated.

Malcohn: Well, keep in mind that I didn't do all that stuff simultaneously.

Eller: That makes me feel a little better.

Malcohn: And I'm turning 51 this year, so I think I might have a few years on you as well.

Eller: Guess what? You don't.

Malcohn: I don't?

Eller: No, you don't.

Malcohn: Wow.

Eller: I just turned 51.

Malcohn: Congratulations.

Eller: Fifty-one about 20-some days ago. Twenty-two days ago.

Malcohn: Wow. A belated happy birthday.

Eller: Well, thank you very much. So let's get a little bit into you. You started writing at an early age, and then you started submitting shortly after that, and when you were very young you made contacts with some serious publishers and editors, before you were even out of high school.

Malcohn: Right.

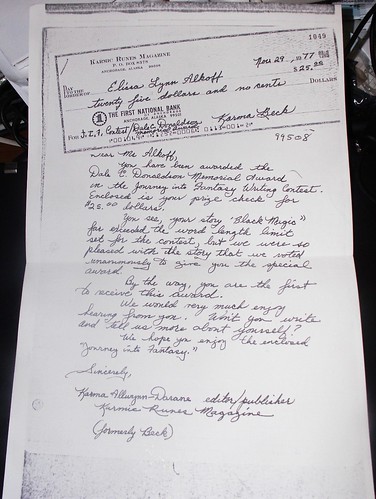

Eller: And then at 15 you finished your first book. You've won several awards and nominations, at least one of which was created especially for you.

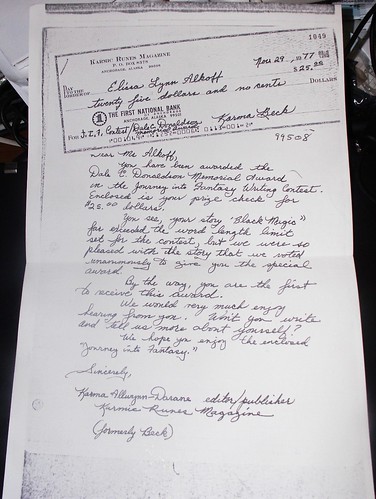

Malcohn: That came out of a small press magazine called Karmic Runes up in Alaska. I don't even know if they're around any more. They had a contest called "Journey into Fantasy." I submitted a story and the next thing I knew they had created an award for my submission, which was pretty cool.

Eller: That is pretty cool. You've won the New England Science Fiction Association Short Story Award. You're a John W. Campbell Award finalist.

Malcohn: Right, and that was all the way back in '85, because there are a bunch of finalists up now on the ballot. The voting is about to begin if it hasn't already started. But I was a finalist back in '85.

Eller: Well, you know what? Being a finalist is being a finalist, no matter what happened.

Malcohn: Right.

[Contains my novelette "Lazuli," my first professional sale after I had published for several years in the small press. "Lazuli" alone made me a finalist for the 1985 John W. Campbell Award.]

Eller: You're a four-time nominee for the Rhysling Award.

Malcohn: And that's given out by the Science Fiction Poetry Association for best speculative poetry of the year.

Eller: And I didn't even know there was a Science Fiction Poetry Association.

Malcohn: They've been around for quite a while. They were founded by Suzette Haden Elgin in 1978; I discovered them in 1980. And for listeners out there -- because I've spoken with people saying, "You mean, they publish SF poetry?" -- the website is www.sfpoetry.com.

[My cover art appears on the September/October 2007 issue of Star*Line, journal of the SFPA. I edited Star*Line from 1986-88.]

Eller: And like I said, I didn't even know there was anything like that out there. This is all news to me. So, on top of everything else, at the moment you have a six-book series that you're proud of.

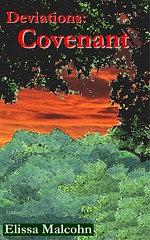

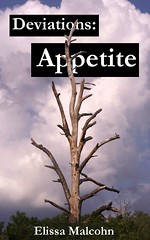

Malcohn: I finished drafting it last year, and the first volume was published by Aisling Press in 2007. Unfortunately, between the economy and various other factors, Aisling has had its share of troubles. As a result, the second volume, Appetite, which was slated to come out next [sic; should be "last"] year, had not been published by Aisling. So I decided that with the economy and with everything else that's going on -- people are asking me, "When is the sequel to Covenant coming out?" Covenant being the first volume. I said, let me release these as free downloads and try to build up a readership. I really have to thank the folks at the MobileReads Forum, because a lot of those folks have come onto my website and taken a look around. Matthew McClintock over at Manybooks.net has picked up the two books as well. I go onto his website and I see people downloading the books. So that makes me feel really good.

Eller: It does make you feel good when somebody's reading your stuff.

Malcohn: Yeah.

Eller: It really does. Well, to continue on, it said that in 2008 "Hermit Crabs" appeared in the Hugo Award nominee Electric Velocipede.

Malcohn: Electric Velocipede, in issue #14.

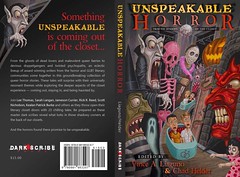

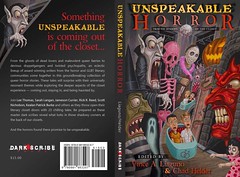

Eller: And you have "Memento Mori" that appeared in Bram Stoker Award finalist Unspeakable Horror.

Malcohn: That's out from Dark Scribe Press. The full title is Unspeakable Horror: From the Shadows of the Closet. That was published in December. That's a Bram Stoker finalist and we'll see how it does next month when they give out the awards. [Unspeakable Horror won the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in an Anthology.]

Eller: And then we continue on. Besides being a novelist and a poet, you're an artist who's exhibited and sold paintings in several galleries in two separate states, as well as at the Mass. College of Art.

Malcohn: Yes. And that was something I picked up. I went through a period, I had a splash in the 1980s getting published, and then my schedule went a little nuts. So I wasn't writing for submission. I can't really say that, because I was being published outside the genre. I was having book reviews published and publishing articles and that sort of thing. But within the science fiction/fantasy genre, I had pretty much dropped off the face of the Earth. And I ended up living in Dorchester, neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. The people in Dorchester throw out the most wonderful items. I'm not going to call them trash, because I was able to pick them up off the street, produce mixed-media art, which is what most of my artwork has been, and that got exhibited and sold. It took a different part of my brain working on the art than it did working on the writing, but I was still able to save my creative sanity that way.

["Before Babel" exhibited at A Strong Cup of Coffee cafe, Dorchester, MA, in January 2002.]

["Totem" was one of two works exhibited at the Massachusetts College of Art and was also exhibited at A Strong Cup of Coffee cafe.]

["Spring" exhibited at the Art Center of Citrus County in Hernando, FL, in December 2004.]

Eller: Well, as if that isn't enough, you also decided that you wanted to become a photographer of some of the most fascinating subjects that a photographer could possibly have: bugs.

Malcohn: Yes. In 2003 I moved from Massachusetts down to Florida, and Florida has the most awesome bugs around because it's tropical, actually subtropical. We'll get katydids that are four inches long, and we'll get moths with a six-inch wingspan. And spiders that are just about as big with the legs. I just got fascinated with these bugs. I picked up, really, my first good camera, which was a digital that had something called a super-macro lens. That means you can get really close up to a bug. I'd photograph spiders and I'd be able to see all their eyes in the photograph, which I couldn't see with my own eyes. The lens would just blow that up. Some of those pictures have been published as well, as well as pictures that I've taken not of bugs.

[My article about bug photography, "A New Lens on Life," includes a photo montage used on the cover of Harp-Strings Poetry Journal, Summer 2007.]

[My photo of beach sunflowers appeared in the online magazine of This Old House in April 2007.]

Eller: What got you interested in photographing bugs?

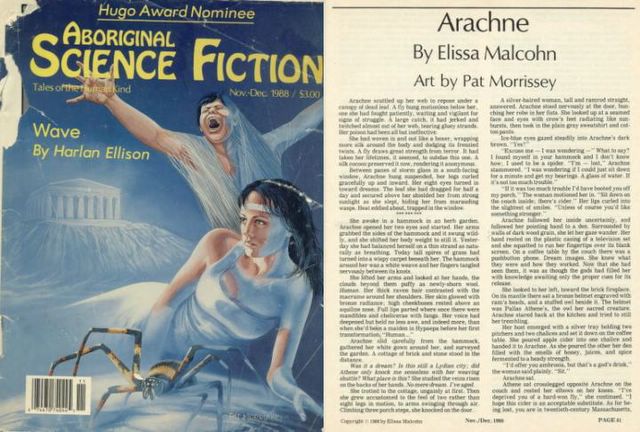

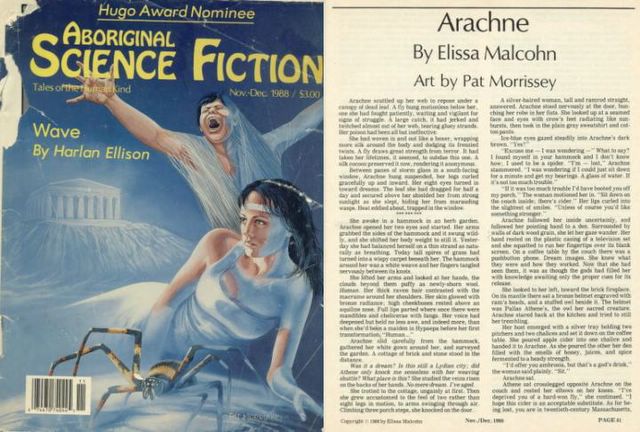

Malcohn: Pretty much the fact that I had a camera that could handle them well, and that they were all around me. And partly, I'd been fascinated with bugs. One story, for example, "Arachne," which originally appeared in Aboriginal Science Fiction in 1988 and was reprinted last year in an anthology called Riffing on Strings: Creative Writing Inspired by String Theory, combines what I've picked up in knowledge about spiders and about cosmic string theory, because you figure strings, spider webs. I could do a neat metaphor with that. And it turned out that -- I actually wrote the story starting in 1986, and in November 1986, Discover magazine, or what is now called Discover -- back then it was called Science 86, and Omni -- I forget which did which offhand, but one came out with an article called "Spider Madness," and the other came out with an article called "Everything is Now Tied to Strings." [Dava Sobel, “Spider Madness,” Omni, and Gary Taubes, “Everything’s Now Tied to Strings,” Science 86.] And with those two articles coming out in the same month, and I was subscribing to both magazines, that juxtaposition just clicked. I started reading up on spiders, and I'd already known about the myth of Arachne, so I kind of wanted to write a sequel to that. And it ended up getting published. So that was pretty cool.

["Arachne" received the cover illustration in the Nov./Dec. 1988 issue of Aboriginal SF. Artist: Pat Morrissey.]

[Riffing on Strings at the Florida Writers Association conference bookstore, November 2008.]

Eller: That is pretty cool. And you just brought up Omni, which is a magazine I have not thought of in years. I used to have a subscription to it. I thought it was absolutely wonderful.

Malcohn: It was a great magazine.

Eller: Well, okay, so let's start at the beginning of you, okay? Now, you seem to be very science fiction-oriented in your writing, or at least in the fiction side of your writing. Can you tell us why science fiction draws you? What is it about the genre that really reaches out and grabs you? When did this all happen to you, and what influences did you have?

Malcohn: I think for me, as far as the writing goes -- I'm trying to remember back to my first exposure to science fiction. It probably was when I was a toddler watching The Outer Limits, the original Outer Limits series. And I was fascinated by it. You know, here was stuff that I wasn't seeing every day. It wasn't part of my toddler-hood growing up, except for what I was watching on television. So that was probably the first science fiction that actually caught my interest. But things didn't really start going for me until Star Trek. And situations in my life kind of aided that, because when I was seven years old I almost died in a car accident. Without going into the gory details, I'll just say I was in critical condition for two weeks and in the hospital for ten weeks, and then on crutches for four months afterwards at the tender age of seven. I had gotten out of Coney Island Hospital in August of 1966, one month before the original Trek series aired. But instead of seeing the very, very first episode that aired, I saw what was actually the second pilot, called, "Where No Man Has Gone Before." And in that, one character, the heavy in fact, dies and comes back to life. That really struck me, because I had kind of just done that in the hospital. And so, Trek became just linked with my life on that deeper level as well as the entertainment level. And then, growing up in New York, with my mother teaching English in an inner city high school and coming home with both horror stories and stories of her students really triumphing against the odds, I grew up with an attachment to social relevance in entertainment. I got attached to the whole New Wave subgenre of science fiction, which deals with social relevance. It deals with taboos and inner space versus outer space. So the science fiction that I grew attached to was not so much rocket science in that sense of the word, but how do the characters deal emotionally and psychologically with the situations they're faced with? Star Trek was very good with social relevance on that end, also, which is another reason why I loved the show so much. My first writing was actually Trek episodes. You know, fanfic before fanfic was quote-unquote "invented," but of course people were writing it back then. It just wasn't called fanfic at the time. And this was not particularly good writing. I mean, I was maybe ten, eleven years old at this point. What it did, though, was it allowed me to create an alter-ego character that I placed on the Enterprise. So in a way I was placing myself on the Enterprise and having a fictional family. And then I jumped off from that and started writing regular science fiction-y type stories and submitting them. Growing up in Brooklyn, I was sending, at that point most of the magazines were in Manhattan. After I had drafted my first novel, if I got a "yes" response to a query letter, I didn't just mail in sample chapters or a manuscript. I hopped on the subway and rode into Manhattan, because I could.

Eller: I am so jealous.

Malcohn: [Laughs] And I feel very lucky to be in a spot now where I can make submissions and communicate with people in the business just through the Internet, using the social networking systems. Coming back after spending more than a decade away from that whole submissions arena, I felt like Rip Van Winkle. Because back in the 80s, for all intents and purposes, you didn't have the Internet. I had to completely relearn the industry, which is in the midst of changing at breakneck speed anyway. So I'm still kind of trying to keep up with it all.

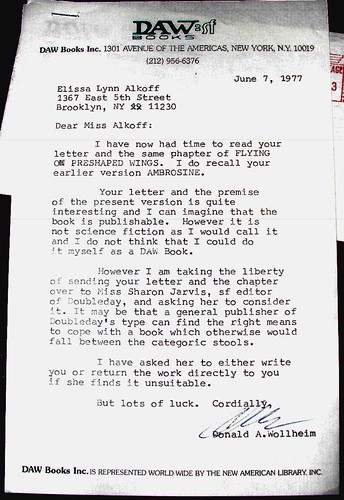

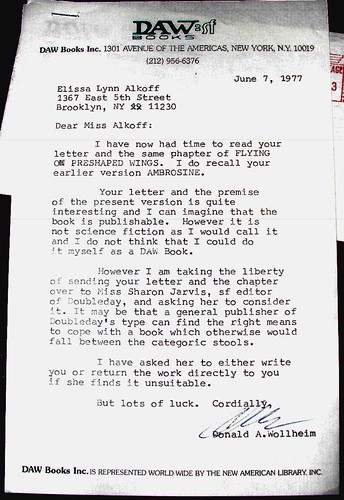

Eller: Yes, it is. When you were 15, you wrote your first novel. And that was the one that you were submitting, and you were hopping the subway, and you were running around, taking your novel in person to the different publishers that said, "Come out and show it to us." And you met Donald Wollheim, the founder of DAW Books.

Malcohn: Yes.

Eller: What was that like?

Malcohn: Well, I was young and I really wasn't fully cognizant of all the attention that I was getting. He was just a wonderful gentleman, and he actually gave me a copy of Tanith Lee's The Birthgrave, which is a wonderful book. He said he saw some similarities there, which was really cool. But in his ultimate rejection, he said, "Give yourself a couple years and try again," and he said, "This is really interesting."

He encouraged me to keep at it, which I did because I wasn't going to not keep at it, no matter what anyone said. And then two years later I wrote my second draft. Again, I'm still developing my writing at this point.

Eller: Yes.

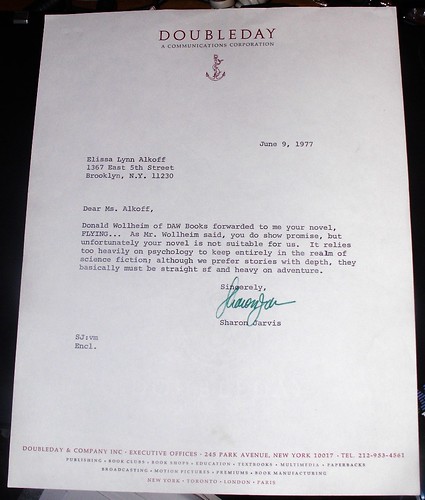

Malcohn: The first book was called Ambrosine. The second book was called Flying on Preshaped Wings. And I submitted it to DAW Books again. And Donald Wollheim sent me a letter back, saying, "I have forwarded this over to Sharon Jarvis at Doubleday."

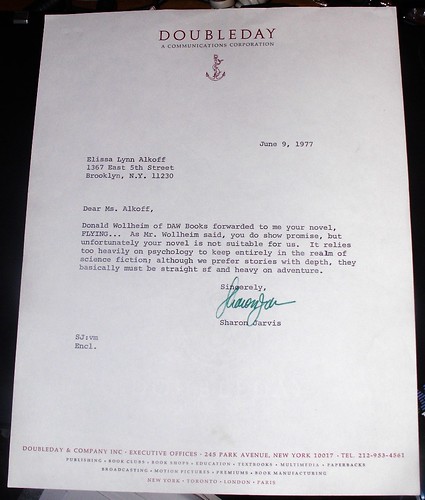

She was an editor at Doubleday at that time. I believe she's now an agent. And that also came back to me. Basically, I was so much into the psychological aspect of the story, that it was not the kind of science fiction adventure that they wanted.

But it was still, you know, I was quite happy that Wollheim took it upon himself -- he said, "This might be publishable," and he forwarded my manuscript on. And here I was, basically, 17 years old. And again, I really didn't know any better. [Laughs] I was doing this for the sake of doing it and getting this wonderful attention, and not really knowing -- I certainly appreciated it, but probably on some level I didn't really know what it all meant.

Eller: Yeah, you had some valuable contacts there, but didn't really know how to utilize them at that point.

Malcohn: Yeah. And also, I was stuck at that point with studying for -- I was in college at that point; I entered college at 16. So I was concentrating on that and the grades. And while in college I worked on the college literary magazine. So I was still keeping my hand in there as well. But in terms of getting involved with the industry as an industry, sometimes I think part of me still doesn't quite get it. [Laughs] I'm still doing it out of love of doing it, balancing it with everything else, and then, you know, when somebody says "yes" to a submission, I'm thrilled. And rejections don't bother me because, you know, I've also taught writing, both science fiction writing and writing in general -- and as I've told my students, "Just keep trying, even if you're getting rejections." Because you may not exactly fit the niche of the magazine. I've had stories turned down vehemently by one magazine that another magazine actually embraced and said, "Yes, this is exactly what we want." So you never know. And you just keep struggling to find that niche and see who says yes. Actually, I just recently learned -- a while back I had had both poetry and fiction accepted to Asimov's, and both my poetry and fiction -- it's a novelette called "Flotsam" and a poem called "Derivative Work" -- and they are both going to appear in the October/November 2009 issue.

Eller: You know, personally I consider seeking publication as a game. And the rejection slips are, you know, just another part of the game.

Malcohn: Exactly.

Eller: It's all fun. It's all challenging. You know, you send the stuff out, you try to find the right place for it to go. And if it doesn't go, you get a rejection slip. Sometimes you get a nice little note with suggestions in it.

Malcohn: Yes, and I especially appreciate that.

Eller: It works out really well. And I like the idea that your science fiction is psychological. A lot of psychological-social. Because I really like delving into the emotions of my characters. I do a lot of internalizing with them. I like to delve into their motivation and their little psychoses and everything else, because I think it makes it a much richer story.

Malcohn: Yes. In the second volume of my series, I bring back a villain who -- you just kind of saw a part of in the first book. After he had done something that was particularly nasty, I stepped back from the manuscript and said, "Okay, I do not want this to become a two-dimensional character. Why is he this way?" Part of my process -- I don't do outlines so much as take scads of notes, and my notes are arguments with myself. They're idea bubbles. I do matrices, a whole bunch of things. But I was trying to figure this guy out. I scribbled notes that figured out, okay, this is his life story. This is what made him what he is. This is what drove him to do what he's done. And that informed me as I then went on and continued with the draft, because then I could really channel him, knowing what he was about. So I look into those motivations and psychology.

Eller: Well, in bringing up psychology again, where do your thoughts and ideas for the characters come from? Now, do you study the people around you to get the ideas? Are you looking for inspiration in movies and television? Or are you reaching within yourself, looking for those little, hidden places of insecurity and doubt that we all have? You know, the places that we like to keep out of the public eye.

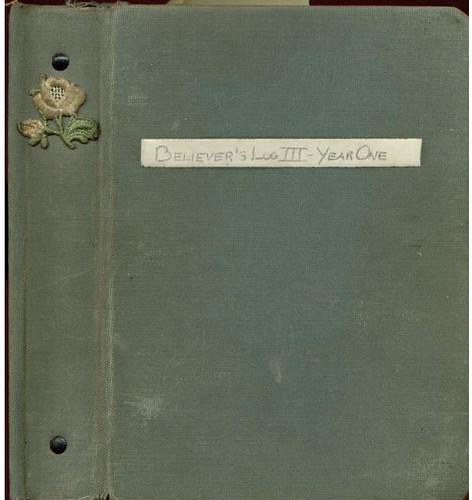

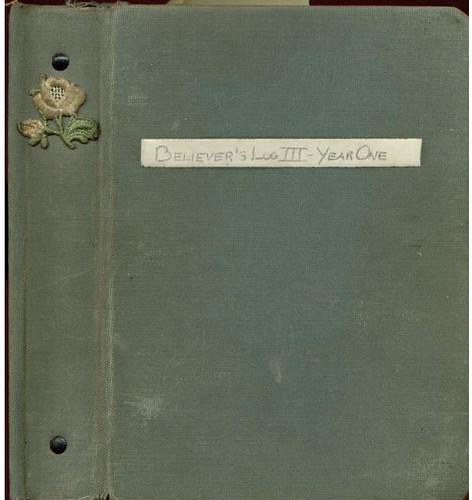

Malcohn: I think mostly I'm looking into myself. There are some inspirations that I draw from outside, but for the most part I'm looking inside. "Hermit Crabs" in Electric Velocipede, to research that, I went through my old diaries as a teenager, because my protagonist is a 15-year-old girl.

[The first of two binders containing my high school diary.]

And so, even though I'm a different generation, a lot of that same angst is there, and it passes from generation to generation. But what I also did was, I was looking at public online diaries of kids that age, because I didn't want to present something that was inaccurate in terms of generational values and language and that sort of thing. So, there, my research was both internal and external. But that's one example.

Eller: You mention going to online journals. And one of the things that bothers me when I read a book is, frequently, the author is writing about somebody who's younger. A little while ago I read one where the main character was six years old for a good quarter of the book. And yet, he was presented in such a way that he was making adult decisions and doing things that were way above their age level. And that really bugged me when he did that.

Malcohn: Yeah, and there's one of two ways to handle that. I'm not saying it's impossible to have someone who is that young, who can make that mature a decision. But, as again I tell my students, you can write about anything as long as you make it believable. And so, if there is a character who is that mature at that young an age, why is that so? Why should the reader believe that of a character? There are certain ways to present information that could make a reader take that leap of faith. But the important thing is to put that detail in, and detail is crucial to believability in writing.

Eller: Yes, it is. But you know what? We need to talk about your series because, if nothing else, you have a book out there for sale, and we would like people to buy it. Or at least, I think you do.

Malcohn: Okay. Well, actually, people don't have to buy it. They can download it for free. So that's what's been getting me some terrific response. As I said, Deviations: Covenant, the first volume of my series, had been published in 2007 by Aisling Press. And I still do have paperbacks that I take to conventions.

[At my sales table during Oasis in May 2009.]

I just came back this past weekend from Oasis, the Orlando annual science fiction, fantasy, and horror convention. Had a wonderful time there. And was selling paperbacks of Covenant, as well as the other material that I'm in. Unfortunately, the situation has been that -- oh, I and some other folks, shall we say, have not received compensation. (Laughs) It's one of those situations. What I will say, though, is that my book is still listed with Amazon, the Aisling Press edition. I think they may have one or two copies left. If readers do want that paperback and do want to order it online, I would ask that they go through my website. People can Google my name or "Malcohn's World". And if you then go to my Deviations website and click on the link -- there's a place to click for how to support other writers. By way of this long introduction, when Covenant was published, I became involved in something called the Circulating Book Plan that the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America has. It's a wonderful way to share books among the authors. By donating books to that plan, what also happened was SFWA has a special Amazon link, so that people using that link, instead of the general Amazon link, a few pennies from that sale go to SFWA's Emergency Medical Fund. So even if I'm not getting any royalty payments because of a small press that fell on hard times, if people buy that book, at least something should go to that medical fund.

Eller: So what's Deviations about? The series, and Covenant specifically?

Malcohn: The series revolves around one big problem that is shared by two subspecies -- some people call them tribes, some people call them races, but they're two subspecies. Both of them are sentient. They have civilizations. The problem is that because of ecological effects and changes, members of one subspecies must eat members of the other to survive. And the dependence runs both ways, because the Yata and the Masari, these two subspecies, are linked to each other socially, economically, and spiritually, as well as nutritionally. That leads to ethical dilemmas and to people on both sides who break the rules. In the first volume, Covenant, I'm dealing with a religious system that is in jeopardy, and then the succeeding volumes present other portions of that problem across the region, because we're dealing with a region of peoples who have largely been separated from each other due to geological and terrain effects. And little by little, you're getting groups of people coming into contact with each other who otherwise would not. You've got a cultural exchange. You've got more ethical dilemmas. And the thrust of the series is, okay, we have this big problem that is really tearing the region and these two peoples apart. How can we solve that problem? And different settlements have different ideas of how to solve that problem, and some are considerably worse than others.

Eller: It sounds rather convoluted and somewhat uncomfortable for the two species.

Malcohn: Yes.

Eller: It should be actually very interesting how you work that out.

Malcohn: I don't want to give away any spoilers, but as I was figuring it out, of course, everything is a double-edged sword. So that every time someone comes across what might be a solution, there's a price to pay.

Eller: Well, we're closing in on the end of the Blog Talk thing. So you'd better put out your e-mail address, your website, whatever you wish to give people.

Malcohn: Okay. My website is through Earthlink, so that's a mile long. It's got a tilde in it. So what I tell people to do is, you can Google my name. That will get a whole slew of stuff, but my website should be at the top. Or they can just Google "Malcohn's World" in quotes. And that should just take them to my website address.

Eller: Okay. Well, that should get people there, because it really sounds like you have a very interesting site with all the connections to the other science fiction authors and books and everything else. That could be a good site for a writer to contact to get the information on that.

Malcohn: For writers, I don't always keep this up as much as I would like to, but I have a Writing, Editing, Research, and Marketing Resources page that has all sorts of neat links on it.

Eller: All right-y. Well, on top of everything else, you're also a freelance writer.

Malcohn: Yes. I do corporate writing and editing, tape transcription. I'm kind of a one-person communications business. And I enjoy doing that immensely, because I work with companies that I learn things from. Those companies deal with the environment, they deal with architecture. Basically all over the map. And in fact, some of my work experience has made its way into the story that's forthcoming in Asimov's. One of the mantras that I live by is that nothing is wasted. Even when I didn't have the time, space, or the presence of mind to write fiction for submission, I was still picking up information and a certain level of being that I was then able to use in the writing when I finally got back to being able to write again.

Eller: Well, what particular skills -- I'm kind of curious about this -- what skills do you think are needed for freelancing that are not needed for science fiction? Or even the other way around, what skills do you think are needed for writing fiction that you don't need for freelancing?

Malcohn: I'm probably going to give you a complicated answer to that, because on the one hand there's a certain type of condensation that I have used. One of my gigs was taking five- and six-thousand-word articles and condensing them into roughly 500-word press releases. You're taking the kernel of information and the main thrust of the article and you're condensing it into the equivalent of a small commercial spot. That also works in fiction writing, especially in writing synopses for novels. In writing blurbs.

Eller: I was just thinking that. [Laughs]

Malcohn: On the other hand, you don't want to do that type of condensation when you need to present enough detail to really flesh out a story or flesh out a character.

Eller: Yeah. I was thinking about the synopsis. The first one I did for my first book, that was trying to condense a 140,000-word book down to one page.

Malcohn: Yeah.

Eller: Not that easy a thing to do. Especially not easy to do it in a way that looks something less than mechanical and chopped up.

Malcohn: Exactly. One of the things that helped me -- as I said, I don't keep outlines -- but when I write something as large as a novel I keep a spreadsheet. And the spreadsheet has what page I'm on, what chapter it is, how long the chapter is, the keywords, and that sort of thing. That has helped me in writing synopses. I go back to those keywords, and if I want to find a particular spot to make a point, I know exactly where to go.

Eller: Okay. So, to finish up, do you have any particular advice for people who want to break into either the freelancing business or writing fiction?

Malcohn: Patience and perseverance are the two magic words. That job that I got condensing the articles into press releases? That had been a cold call, and I think that day I had already made 20 calls and gotten "No"s. And something like the twenty-third or twenty-fourth call got a "Yes." It's the same thing with submitting. It's a case of doing your research, also. You want to find a client or a magazine that your story will fit. Sometimes it's easy to tell, and sometimes it's more difficult. It's just a question of, you've got to keep trying. Keep the faith. Keep polishing your stuff. Format is very important. There are some people who say, "You know, the story should stand on its own without the formatting." Well, not necessarily the case. I've listened to editors on panels who say they have turned down stories just because the format was not what they wanted, and it told them that the person submitting didn't know how to follow directions. Sometimes it gets to be as simple as that. I also tell people that if you're using something like Writer's Market, if the listing in Writer's Market provides a website, go check the website. Because the print book is coming out roughly, what, a year after the information has been submitted. You can have situations where what's in the hardback book and what's on the website disagree with each other. You want to make sure that you keep on top of things. But just keep trying. Keep polishing stuff. I'm very aware, now that I'm releasing my own books, I want to make them as good as I can make them, because it's my responsibility to readers. I want to give them a good product no matter where that product comes from. No matter if I publish it myself or it goes through a regular publisher. So have faith in the work and respect the work. Do it not only for yourself but for the readers and the characters and for that whole process, because it's really a wonderful adventure.

Eller: I want to go back a little bit to having everything in the right format when you're submitting. That goes back to the fact that book publishers and magazines and the publishers and everybody else get hundreds and hundreds of submissions for every one that they need. So they're in a position where they're actually looking for a reason to reject the story at that point, because they have so many of them that they want something that fits exactly their needs. And one of the ways to show that is the fact that you have set your story up in the format that's exactly the way they want, which shows that you have done your homework. That you care about what you're submitting.

Malcohn: Exactly. If an editor is used to looking at a particular format, if something is submitted that detracts from that, it decreases the readability. And if you're stuck reading hundreds, thousands of manuscripts, you want them to be as readable as they can possibly be. There are some formats that go well outside what is called the standard. I don't have the website right in front of me, but if listeners out there want to get a good guide for standard format, Google William Shunn's name. He's put together a wonderful formatting guide. There are others out there, but I've tended to use his when I'm submitting to publications that want standard format. Now, that said, when you come across a publication, it may ask for a completely different format. I had a story in a magazine that no longer is publishing. It was an e-zine called Helix: A Speculative Fiction Quarterly. They were on the ballot for a Hugo last year. When I got the go-ahead to submit, I was asked to submit my manuscript in single-spaced 14-point Arial, which sounds like it breaks all the rules. But that's what I submitted it in, because that's what the editor wanted. And it's very important to follow those directions, for the sake of telling an editor that, yes, you can follow directions, and to make your manuscript readable the way the editor wants to read it.

[Read a .pdf file of "Prometheus Rebound" here.]

Eller: And once again, going back to the submission thing, I just wanted to throw out Ralan.com. That is, for those of you listening, an excellent site for people who looking for magazines to submit to. They have a large compendium of magazines running, from "for the love of it" to semipro to pro magazines. And the three different categories for science fiction and horror writing, fantasy. It's an excellent, excellent place to go to find places to submit your work.

Malcohn: Yes. I've gone through Ralan many a time to look for places to submit. Another good online guide for people who write in genres other than or in addition to science fiction, fantasy, and horror, is Duotrope.com. They do some very impressive breakdowns of here's the pay scale, here's the length we want, as well as the genre and a whole bunch of other information about the particular market.

Eller: Okay, well, our time was up actually about nine minutes ago, and we just continued carrying on. So thank you very much for being my guest today.

Malcohn: Great, thanks a lot, Mark. I appreciate it.

Eller: And really, have a very good rest of the evening.

Malcohn: Thanks. You, too.

Eller: Okay.

Malcohn: Okay, good talking with you.

Eller: It was nice talking to you. And for the listeners, thank you for visiting Chronicles. And goodbye.

Vol. 1, Deviations: Covenant (2nd Ed.)

Vol. 2, Deviations: Appetite

Free downloads of both volumes here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License.

Back on May 28, I was interviewed by Mark Eller, host of Chronicles, also on BTR. That show is now available as a podcast here and elsewhere.

As someone on dial-up, I know how it feels to wait through a download. With that in mind -- and to provide links to websites Mark and I mentioned, along with some accompanying photos -- I've transcribed the show, cleaning up some word repetitions and the like. Click below for the transcript.

Chronicles, May 28, 2009

Mark Eller: Hello, everybody. This is Chronicles, and I am your host, Mark Eller. And we are here today to speak with Elissa -- how do you pronounce your last name, Elissa?

Elissa Malcohn: It's [El-EE-sa Mal-KOHN].

Eller: Elissa Malcohn. Thank you. I wasn't really sure how to pronounce that.

Malcohn: Oh, that goes back a long ways. People have been mispronouncing my name for decades. That's okay.

Eller: How are you doing today, Elissa?

Malcohn: I'm doing fine. I'd like to thank you very much for having me on the show.

Eller: I would like to thank you very much for coming on to the show. It's an honor to have you here, because, to tell you the truth, I was looking over your bio, and you make me feel a little bit tired. I have a habit with that with my guests so far. They all make me feel a little bit tired and somewhat unmotivated.

Malcohn: Well, keep in mind that I didn't do all that stuff simultaneously.

Eller: That makes me feel a little better.

Malcohn: And I'm turning 51 this year, so I think I might have a few years on you as well.

Eller: Guess what? You don't.

Malcohn: I don't?

Eller: No, you don't.

Malcohn: Wow.

Eller: I just turned 51.

Malcohn: Congratulations.

Eller: Fifty-one about 20-some days ago. Twenty-two days ago.

Malcohn: Wow. A belated happy birthday.

Eller: Well, thank you very much. So let's get a little bit into you. You started writing at an early age, and then you started submitting shortly after that, and when you were very young you made contacts with some serious publishers and editors, before you were even out of high school.

Malcohn: Right.

Eller: And then at 15 you finished your first book. You've won several awards and nominations, at least one of which was created especially for you.

Malcohn: That came out of a small press magazine called Karmic Runes up in Alaska. I don't even know if they're around any more. They had a contest called "Journey into Fantasy." I submitted a story and the next thing I knew they had created an award for my submission, which was pretty cool.

Eller: That is pretty cool. You've won the New England Science Fiction Association Short Story Award. You're a John W. Campbell Award finalist.

Malcohn: Right, and that was all the way back in '85, because there are a bunch of finalists up now on the ballot. The voting is about to begin if it hasn't already started. But I was a finalist back in '85.

Eller: Well, you know what? Being a finalist is being a finalist, no matter what happened.

Malcohn: Right.

[Contains my novelette "Lazuli," my first professional sale after I had published for several years in the small press. "Lazuli" alone made me a finalist for the 1985 John W. Campbell Award.]

Eller: You're a four-time nominee for the Rhysling Award.

Malcohn: And that's given out by the Science Fiction Poetry Association for best speculative poetry of the year.

Eller: And I didn't even know there was a Science Fiction Poetry Association.

Malcohn: They've been around for quite a while. They were founded by Suzette Haden Elgin in 1978; I discovered them in 1980. And for listeners out there -- because I've spoken with people saying, "You mean, they publish SF poetry?" -- the website is www.sfpoetry.com.

[My cover art appears on the September/October 2007 issue of Star*Line, journal of the SFPA. I edited Star*Line from 1986-88.]

Eller: And like I said, I didn't even know there was anything like that out there. This is all news to me. So, on top of everything else, at the moment you have a six-book series that you're proud of.

Malcohn: I finished drafting it last year, and the first volume was published by Aisling Press in 2007. Unfortunately, between the economy and various other factors, Aisling has had its share of troubles. As a result, the second volume, Appetite, which was slated to come out next [sic; should be "last"] year, had not been published by Aisling. So I decided that with the economy and with everything else that's going on -- people are asking me, "When is the sequel to Covenant coming out?" Covenant being the first volume. I said, let me release these as free downloads and try to build up a readership. I really have to thank the folks at the MobileReads Forum, because a lot of those folks have come onto my website and taken a look around. Matthew McClintock over at Manybooks.net has picked up the two books as well. I go onto his website and I see people downloading the books. So that makes me feel really good.

Eller: It does make you feel good when somebody's reading your stuff.

Malcohn: Yeah.

Eller: It really does. Well, to continue on, it said that in 2008 "Hermit Crabs" appeared in the Hugo Award nominee Electric Velocipede.

Malcohn: Electric Velocipede, in issue #14.

Eller: And you have "Memento Mori" that appeared in Bram Stoker Award finalist Unspeakable Horror.

Malcohn: That's out from Dark Scribe Press. The full title is Unspeakable Horror: From the Shadows of the Closet. That was published in December. That's a Bram Stoker finalist and we'll see how it does next month when they give out the awards. [Unspeakable Horror won the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in an Anthology.]

Eller: And then we continue on. Besides being a novelist and a poet, you're an artist who's exhibited and sold paintings in several galleries in two separate states, as well as at the Mass. College of Art.

Malcohn: Yes. And that was something I picked up. I went through a period, I had a splash in the 1980s getting published, and then my schedule went a little nuts. So I wasn't writing for submission. I can't really say that, because I was being published outside the genre. I was having book reviews published and publishing articles and that sort of thing. But within the science fiction/fantasy genre, I had pretty much dropped off the face of the Earth. And I ended up living in Dorchester, neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. The people in Dorchester throw out the most wonderful items. I'm not going to call them trash, because I was able to pick them up off the street, produce mixed-media art, which is what most of my artwork has been, and that got exhibited and sold. It took a different part of my brain working on the art than it did working on the writing, but I was still able to save my creative sanity that way.

["Before Babel" exhibited at A Strong Cup of Coffee cafe, Dorchester, MA, in January 2002.]

["Totem" was one of two works exhibited at the Massachusetts College of Art and was also exhibited at A Strong Cup of Coffee cafe.]

["Spring" exhibited at the Art Center of Citrus County in Hernando, FL, in December 2004.]

Eller: Well, as if that isn't enough, you also decided that you wanted to become a photographer of some of the most fascinating subjects that a photographer could possibly have: bugs.

Malcohn: Yes. In 2003 I moved from Massachusetts down to Florida, and Florida has the most awesome bugs around because it's tropical, actually subtropical. We'll get katydids that are four inches long, and we'll get moths with a six-inch wingspan. And spiders that are just about as big with the legs. I just got fascinated with these bugs. I picked up, really, my first good camera, which was a digital that had something called a super-macro lens. That means you can get really close up to a bug. I'd photograph spiders and I'd be able to see all their eyes in the photograph, which I couldn't see with my own eyes. The lens would just blow that up. Some of those pictures have been published as well, as well as pictures that I've taken not of bugs.

[My article about bug photography, "A New Lens on Life," includes a photo montage used on the cover of Harp-Strings Poetry Journal, Summer 2007.]

[My photo of beach sunflowers appeared in the online magazine of This Old House in April 2007.]

Eller: What got you interested in photographing bugs?

Malcohn: Pretty much the fact that I had a camera that could handle them well, and that they were all around me. And partly, I'd been fascinated with bugs. One story, for example, "Arachne," which originally appeared in Aboriginal Science Fiction in 1988 and was reprinted last year in an anthology called Riffing on Strings: Creative Writing Inspired by String Theory, combines what I've picked up in knowledge about spiders and about cosmic string theory, because you figure strings, spider webs. I could do a neat metaphor with that. And it turned out that -- I actually wrote the story starting in 1986, and in November 1986, Discover magazine, or what is now called Discover -- back then it was called Science 86, and Omni -- I forget which did which offhand, but one came out with an article called "Spider Madness," and the other came out with an article called "Everything is Now Tied to Strings." [Dava Sobel, “Spider Madness,” Omni, and Gary Taubes, “Everything’s Now Tied to Strings,” Science 86.] And with those two articles coming out in the same month, and I was subscribing to both magazines, that juxtaposition just clicked. I started reading up on spiders, and I'd already known about the myth of Arachne, so I kind of wanted to write a sequel to that. And it ended up getting published. So that was pretty cool.

["Arachne" received the cover illustration in the Nov./Dec. 1988 issue of Aboriginal SF. Artist: Pat Morrissey.]

[Riffing on Strings at the Florida Writers Association conference bookstore, November 2008.]

Eller: That is pretty cool. And you just brought up Omni, which is a magazine I have not thought of in years. I used to have a subscription to it. I thought it was absolutely wonderful.

Malcohn: It was a great magazine.

Eller: Well, okay, so let's start at the beginning of you, okay? Now, you seem to be very science fiction-oriented in your writing, or at least in the fiction side of your writing. Can you tell us why science fiction draws you? What is it about the genre that really reaches out and grabs you? When did this all happen to you, and what influences did you have?

Malcohn: I think for me, as far as the writing goes -- I'm trying to remember back to my first exposure to science fiction. It probably was when I was a toddler watching The Outer Limits, the original Outer Limits series. And I was fascinated by it. You know, here was stuff that I wasn't seeing every day. It wasn't part of my toddler-hood growing up, except for what I was watching on television. So that was probably the first science fiction that actually caught my interest. But things didn't really start going for me until Star Trek. And situations in my life kind of aided that, because when I was seven years old I almost died in a car accident. Without going into the gory details, I'll just say I was in critical condition for two weeks and in the hospital for ten weeks, and then on crutches for four months afterwards at the tender age of seven. I had gotten out of Coney Island Hospital in August of 1966, one month before the original Trek series aired. But instead of seeing the very, very first episode that aired, I saw what was actually the second pilot, called, "Where No Man Has Gone Before." And in that, one character, the heavy in fact, dies and comes back to life. That really struck me, because I had kind of just done that in the hospital. And so, Trek became just linked with my life on that deeper level as well as the entertainment level. And then, growing up in New York, with my mother teaching English in an inner city high school and coming home with both horror stories and stories of her students really triumphing against the odds, I grew up with an attachment to social relevance in entertainment. I got attached to the whole New Wave subgenre of science fiction, which deals with social relevance. It deals with taboos and inner space versus outer space. So the science fiction that I grew attached to was not so much rocket science in that sense of the word, but how do the characters deal emotionally and psychologically with the situations they're faced with? Star Trek was very good with social relevance on that end, also, which is another reason why I loved the show so much. My first writing was actually Trek episodes. You know, fanfic before fanfic was quote-unquote "invented," but of course people were writing it back then. It just wasn't called fanfic at the time. And this was not particularly good writing. I mean, I was maybe ten, eleven years old at this point. What it did, though, was it allowed me to create an alter-ego character that I placed on the Enterprise. So in a way I was placing myself on the Enterprise and having a fictional family. And then I jumped off from that and started writing regular science fiction-y type stories and submitting them. Growing up in Brooklyn, I was sending, at that point most of the magazines were in Manhattan. After I had drafted my first novel, if I got a "yes" response to a query letter, I didn't just mail in sample chapters or a manuscript. I hopped on the subway and rode into Manhattan, because I could.

Eller: I am so jealous.

Malcohn: [Laughs] And I feel very lucky to be in a spot now where I can make submissions and communicate with people in the business just through the Internet, using the social networking systems. Coming back after spending more than a decade away from that whole submissions arena, I felt like Rip Van Winkle. Because back in the 80s, for all intents and purposes, you didn't have the Internet. I had to completely relearn the industry, which is in the midst of changing at breakneck speed anyway. So I'm still kind of trying to keep up with it all.

Eller: Yes, it is. When you were 15, you wrote your first novel. And that was the one that you were submitting, and you were hopping the subway, and you were running around, taking your novel in person to the different publishers that said, "Come out and show it to us." And you met Donald Wollheim, the founder of DAW Books.

Malcohn: Yes.

Eller: What was that like?

Malcohn: Well, I was young and I really wasn't fully cognizant of all the attention that I was getting. He was just a wonderful gentleman, and he actually gave me a copy of Tanith Lee's The Birthgrave, which is a wonderful book. He said he saw some similarities there, which was really cool. But in his ultimate rejection, he said, "Give yourself a couple years and try again," and he said, "This is really interesting."

He encouraged me to keep at it, which I did because I wasn't going to not keep at it, no matter what anyone said. And then two years later I wrote my second draft. Again, I'm still developing my writing at this point.

Eller: Yes.

Malcohn: The first book was called Ambrosine. The second book was called Flying on Preshaped Wings. And I submitted it to DAW Books again. And Donald Wollheim sent me a letter back, saying, "I have forwarded this over to Sharon Jarvis at Doubleday."

She was an editor at Doubleday at that time. I believe she's now an agent. And that also came back to me. Basically, I was so much into the psychological aspect of the story, that it was not the kind of science fiction adventure that they wanted.

But it was still, you know, I was quite happy that Wollheim took it upon himself -- he said, "This might be publishable," and he forwarded my manuscript on. And here I was, basically, 17 years old. And again, I really didn't know any better. [Laughs] I was doing this for the sake of doing it and getting this wonderful attention, and not really knowing -- I certainly appreciated it, but probably on some level I didn't really know what it all meant.

Eller: Yeah, you had some valuable contacts there, but didn't really know how to utilize them at that point.

Malcohn: Yeah. And also, I was stuck at that point with studying for -- I was in college at that point; I entered college at 16. So I was concentrating on that and the grades. And while in college I worked on the college literary magazine. So I was still keeping my hand in there as well. But in terms of getting involved with the industry as an industry, sometimes I think part of me still doesn't quite get it. [Laughs] I'm still doing it out of love of doing it, balancing it with everything else, and then, you know, when somebody says "yes" to a submission, I'm thrilled. And rejections don't bother me because, you know, I've also taught writing, both science fiction writing and writing in general -- and as I've told my students, "Just keep trying, even if you're getting rejections." Because you may not exactly fit the niche of the magazine. I've had stories turned down vehemently by one magazine that another magazine actually embraced and said, "Yes, this is exactly what we want." So you never know. And you just keep struggling to find that niche and see who says yes. Actually, I just recently learned -- a while back I had had both poetry and fiction accepted to Asimov's, and both my poetry and fiction -- it's a novelette called "Flotsam" and a poem called "Derivative Work" -- and they are both going to appear in the October/November 2009 issue.

Eller: You know, personally I consider seeking publication as a game. And the rejection slips are, you know, just another part of the game.

Malcohn: Exactly.

Eller: It's all fun. It's all challenging. You know, you send the stuff out, you try to find the right place for it to go. And if it doesn't go, you get a rejection slip. Sometimes you get a nice little note with suggestions in it.

Malcohn: Yes, and I especially appreciate that.

Eller: It works out really well. And I like the idea that your science fiction is psychological. A lot of psychological-social. Because I really like delving into the emotions of my characters. I do a lot of internalizing with them. I like to delve into their motivation and their little psychoses and everything else, because I think it makes it a much richer story.

Malcohn: Yes. In the second volume of my series, I bring back a villain who -- you just kind of saw a part of in the first book. After he had done something that was particularly nasty, I stepped back from the manuscript and said, "Okay, I do not want this to become a two-dimensional character. Why is he this way?" Part of my process -- I don't do outlines so much as take scads of notes, and my notes are arguments with myself. They're idea bubbles. I do matrices, a whole bunch of things. But I was trying to figure this guy out. I scribbled notes that figured out, okay, this is his life story. This is what made him what he is. This is what drove him to do what he's done. And that informed me as I then went on and continued with the draft, because then I could really channel him, knowing what he was about. So I look into those motivations and psychology.

Eller: Well, in bringing up psychology again, where do your thoughts and ideas for the characters come from? Now, do you study the people around you to get the ideas? Are you looking for inspiration in movies and television? Or are you reaching within yourself, looking for those little, hidden places of insecurity and doubt that we all have? You know, the places that we like to keep out of the public eye.

Malcohn: I think mostly I'm looking into myself. There are some inspirations that I draw from outside, but for the most part I'm looking inside. "Hermit Crabs" in Electric Velocipede, to research that, I went through my old diaries as a teenager, because my protagonist is a 15-year-old girl.

[The first of two binders containing my high school diary.]

And so, even though I'm a different generation, a lot of that same angst is there, and it passes from generation to generation. But what I also did was, I was looking at public online diaries of kids that age, because I didn't want to present something that was inaccurate in terms of generational values and language and that sort of thing. So, there, my research was both internal and external. But that's one example.

Eller: You mention going to online journals. And one of the things that bothers me when I read a book is, frequently, the author is writing about somebody who's younger. A little while ago I read one where the main character was six years old for a good quarter of the book. And yet, he was presented in such a way that he was making adult decisions and doing things that were way above their age level. And that really bugged me when he did that.

Malcohn: Yeah, and there's one of two ways to handle that. I'm not saying it's impossible to have someone who is that young, who can make that mature a decision. But, as again I tell my students, you can write about anything as long as you make it believable. And so, if there is a character who is that mature at that young an age, why is that so? Why should the reader believe that of a character? There are certain ways to present information that could make a reader take that leap of faith. But the important thing is to put that detail in, and detail is crucial to believability in writing.

Eller: Yes, it is. But you know what? We need to talk about your series because, if nothing else, you have a book out there for sale, and we would like people to buy it. Or at least, I think you do.

Malcohn: Okay. Well, actually, people don't have to buy it. They can download it for free. So that's what's been getting me some terrific response. As I said, Deviations: Covenant, the first volume of my series, had been published in 2007 by Aisling Press. And I still do have paperbacks that I take to conventions.

[At my sales table during Oasis in May 2009.]

I just came back this past weekend from Oasis, the Orlando annual science fiction, fantasy, and horror convention. Had a wonderful time there. And was selling paperbacks of Covenant, as well as the other material that I'm in. Unfortunately, the situation has been that -- oh, I and some other folks, shall we say, have not received compensation. (Laughs) It's one of those situations. What I will say, though, is that my book is still listed with Amazon, the Aisling Press edition. I think they may have one or two copies left. If readers do want that paperback and do want to order it online, I would ask that they go through my website. People can Google my name or "Malcohn's World". And if you then go to my Deviations website and click on the link -- there's a place to click for how to support other writers. By way of this long introduction, when Covenant was published, I became involved in something called the Circulating Book Plan that the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America has. It's a wonderful way to share books among the authors. By donating books to that plan, what also happened was SFWA has a special Amazon link, so that people using that link, instead of the general Amazon link, a few pennies from that sale go to SFWA's Emergency Medical Fund. So even if I'm not getting any royalty payments because of a small press that fell on hard times, if people buy that book, at least something should go to that medical fund.

Eller: So what's Deviations about? The series, and Covenant specifically?

Malcohn: The series revolves around one big problem that is shared by two subspecies -- some people call them tribes, some people call them races, but they're two subspecies. Both of them are sentient. They have civilizations. The problem is that because of ecological effects and changes, members of one subspecies must eat members of the other to survive. And the dependence runs both ways, because the Yata and the Masari, these two subspecies, are linked to each other socially, economically, and spiritually, as well as nutritionally. That leads to ethical dilemmas and to people on both sides who break the rules. In the first volume, Covenant, I'm dealing with a religious system that is in jeopardy, and then the succeeding volumes present other portions of that problem across the region, because we're dealing with a region of peoples who have largely been separated from each other due to geological and terrain effects. And little by little, you're getting groups of people coming into contact with each other who otherwise would not. You've got a cultural exchange. You've got more ethical dilemmas. And the thrust of the series is, okay, we have this big problem that is really tearing the region and these two peoples apart. How can we solve that problem? And different settlements have different ideas of how to solve that problem, and some are considerably worse than others.

Eller: It sounds rather convoluted and somewhat uncomfortable for the two species.

Malcohn: Yes.

Eller: It should be actually very interesting how you work that out.

Malcohn: I don't want to give away any spoilers, but as I was figuring it out, of course, everything is a double-edged sword. So that every time someone comes across what might be a solution, there's a price to pay.

Eller: Well, we're closing in on the end of the Blog Talk thing. So you'd better put out your e-mail address, your website, whatever you wish to give people.

Malcohn: Okay. My website is through Earthlink, so that's a mile long. It's got a tilde in it. So what I tell people to do is, you can Google my name. That will get a whole slew of stuff, but my website should be at the top. Or they can just Google "Malcohn's World" in quotes. And that should just take them to my website address.

Eller: Okay. Well, that should get people there, because it really sounds like you have a very interesting site with all the connections to the other science fiction authors and books and everything else. That could be a good site for a writer to contact to get the information on that.

Malcohn: For writers, I don't always keep this up as much as I would like to, but I have a Writing, Editing, Research, and Marketing Resources page that has all sorts of neat links on it.

Eller: All right-y. Well, on top of everything else, you're also a freelance writer.

Malcohn: Yes. I do corporate writing and editing, tape transcription. I'm kind of a one-person communications business. And I enjoy doing that immensely, because I work with companies that I learn things from. Those companies deal with the environment, they deal with architecture. Basically all over the map. And in fact, some of my work experience has made its way into the story that's forthcoming in Asimov's. One of the mantras that I live by is that nothing is wasted. Even when I didn't have the time, space, or the presence of mind to write fiction for submission, I was still picking up information and a certain level of being that I was then able to use in the writing when I finally got back to being able to write again.

Eller: Well, what particular skills -- I'm kind of curious about this -- what skills do you think are needed for freelancing that are not needed for science fiction? Or even the other way around, what skills do you think are needed for writing fiction that you don't need for freelancing?

Malcohn: I'm probably going to give you a complicated answer to that, because on the one hand there's a certain type of condensation that I have used. One of my gigs was taking five- and six-thousand-word articles and condensing them into roughly 500-word press releases. You're taking the kernel of information and the main thrust of the article and you're condensing it into the equivalent of a small commercial spot. That also works in fiction writing, especially in writing synopses for novels. In writing blurbs.

Eller: I was just thinking that. [Laughs]

Malcohn: On the other hand, you don't want to do that type of condensation when you need to present enough detail to really flesh out a story or flesh out a character.

Eller: Yeah. I was thinking about the synopsis. The first one I did for my first book, that was trying to condense a 140,000-word book down to one page.

Malcohn: Yeah.

Eller: Not that easy a thing to do. Especially not easy to do it in a way that looks something less than mechanical and chopped up.

Malcohn: Exactly. One of the things that helped me -- as I said, I don't keep outlines -- but when I write something as large as a novel I keep a spreadsheet. And the spreadsheet has what page I'm on, what chapter it is, how long the chapter is, the keywords, and that sort of thing. That has helped me in writing synopses. I go back to those keywords, and if I want to find a particular spot to make a point, I know exactly where to go.

Eller: Okay. So, to finish up, do you have any particular advice for people who want to break into either the freelancing business or writing fiction?

Malcohn: Patience and perseverance are the two magic words. That job that I got condensing the articles into press releases? That had been a cold call, and I think that day I had already made 20 calls and gotten "No"s. And something like the twenty-third or twenty-fourth call got a "Yes." It's the same thing with submitting. It's a case of doing your research, also. You want to find a client or a magazine that your story will fit. Sometimes it's easy to tell, and sometimes it's more difficult. It's just a question of, you've got to keep trying. Keep the faith. Keep polishing your stuff. Format is very important. There are some people who say, "You know, the story should stand on its own without the formatting." Well, not necessarily the case. I've listened to editors on panels who say they have turned down stories just because the format was not what they wanted, and it told them that the person submitting didn't know how to follow directions. Sometimes it gets to be as simple as that. I also tell people that if you're using something like Writer's Market, if the listing in Writer's Market provides a website, go check the website. Because the print book is coming out roughly, what, a year after the information has been submitted. You can have situations where what's in the hardback book and what's on the website disagree with each other. You want to make sure that you keep on top of things. But just keep trying. Keep polishing stuff. I'm very aware, now that I'm releasing my own books, I want to make them as good as I can make them, because it's my responsibility to readers. I want to give them a good product no matter where that product comes from. No matter if I publish it myself or it goes through a regular publisher. So have faith in the work and respect the work. Do it not only for yourself but for the readers and the characters and for that whole process, because it's really a wonderful adventure.

Eller: I want to go back a little bit to having everything in the right format when you're submitting. That goes back to the fact that book publishers and magazines and the publishers and everybody else get hundreds and hundreds of submissions for every one that they need. So they're in a position where they're actually looking for a reason to reject the story at that point, because they have so many of them that they want something that fits exactly their needs. And one of the ways to show that is the fact that you have set your story up in the format that's exactly the way they want, which shows that you have done your homework. That you care about what you're submitting.

Malcohn: Exactly. If an editor is used to looking at a particular format, if something is submitted that detracts from that, it decreases the readability. And if you're stuck reading hundreds, thousands of manuscripts, you want them to be as readable as they can possibly be. There are some formats that go well outside what is called the standard. I don't have the website right in front of me, but if listeners out there want to get a good guide for standard format, Google William Shunn's name. He's put together a wonderful formatting guide. There are others out there, but I've tended to use his when I'm submitting to publications that want standard format. Now, that said, when you come across a publication, it may ask for a completely different format. I had a story in a magazine that no longer is publishing. It was an e-zine called Helix: A Speculative Fiction Quarterly. They were on the ballot for a Hugo last year. When I got the go-ahead to submit, I was asked to submit my manuscript in single-spaced 14-point Arial, which sounds like it breaks all the rules. But that's what I submitted it in, because that's what the editor wanted. And it's very important to follow those directions, for the sake of telling an editor that, yes, you can follow directions, and to make your manuscript readable the way the editor wants to read it.

[Read a .pdf file of "Prometheus Rebound" here.]

Eller: And once again, going back to the submission thing, I just wanted to throw out Ralan.com. That is, for those of you listening, an excellent site for people who looking for magazines to submit to. They have a large compendium of magazines running, from "for the love of it" to semipro to pro magazines. And the three different categories for science fiction and horror writing, fantasy. It's an excellent, excellent place to go to find places to submit your work.

Malcohn: Yes. I've gone through Ralan many a time to look for places to submit. Another good online guide for people who write in genres other than or in addition to science fiction, fantasy, and horror, is Duotrope.com. They do some very impressive breakdowns of here's the pay scale, here's the length we want, as well as the genre and a whole bunch of other information about the particular market.

Eller: Okay, well, our time was up actually about nine minutes ago, and we just continued carrying on. So thank you very much for being my guest today.

Malcohn: Great, thanks a lot, Mark. I appreciate it.

Eller: And really, have a very good rest of the evening.

Malcohn: Thanks. You, too.

Eller: Okay.

Malcohn: Okay, good talking with you.

Eller: It was nice talking to you. And for the listeners, thank you for visiting Chronicles. And goodbye.

|  |

Vol. 2, Deviations: Appetite

Free downloads of both volumes here.

| Go to Manybooks.net to access Covenant and Appetite in even more formats! |

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home