My Life as a Pigeon

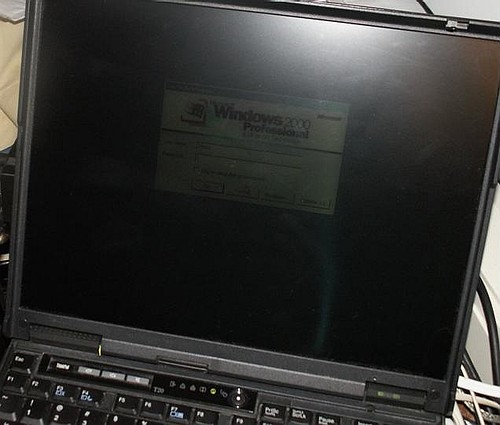

Today the backlight for my computer screen took almost 4 hours to come on. Yesterday I placed an order for a new (well, reconditioned-new) computer -- especially since an out-of-warranty repair on this one would cost almost as much. My screen itself still works fine, as is evidenced by the log-in box that barely shows through a dark haze. I am working happily with it now, and all is right with the world -- until the screen goes dark.

I believe I now know what B.F. Skinner's "superstitious pigeons" felt like....

In Skinner's classic "operant conditioning" experiments, an animal (generally a rat or pigeon) had to learn to perform an action in order to get food. Until that action was performed, no food was forthcoming. As an undergraduate psychology student I'd had the opportunity to condition a rat to press a bar for his dinner.

In his 1947 article, "'Superstition' in the Pigeon", Skinner described how his subjects engaged repeatedly in bizarre behaviors because the birds happened to be performing them when food arrived.

"If a clock is now arranged to present the food hopper at regular intervals with no reference whatsoever to the bird's behavior," he wrote, "operant conditioning usually takes place....One bird was conditioned to turn counter-clockwise about the cage, making two or three turns between reinforcements. Another repeatedly thrust its head into one of the upper corners of the cage. A third developed a 'tossing' response, as if placing its head beneath an invisible bar and lifting it repeatedly. Two birds developed a pendulum motion of the head and body, in which the head was extended forward and swung from right to left with a sharp movement followed by a somewhat slower return. The body generally followed the movement and a few steps might be taken when it was extensive. Another bird was conditioned to make incomplete pecking or brushing movements directed toward but not touching the floor...."

These days, I am the pigeon. My computer is my cage, and the backlight for my screen is a Noyes pellet. To get my backlight to come on, I have tried (a) cooling the computer with fans, (b) tweaking the screen back and forth, (c) toggling the light controls available to me, (d) holding down the Function key for at least 10 seconds (as recommended by tech support), (e) toggling the external monitor control (ditto), (f) running PC-Doctor (ditto), (g) changing my screen saver defaults, (h) shaking the computer (and hearing pretty chiming sounds), and, most recently, (i) slapping the keys.

The backlight has come on -- at least once -- while I've done (a), (b), (g), (h), and/or (i). But, like the stock market, previous behavior is not an indicator of future performance. Sure enough, no sooner had I experienced the thrill of a technique that "worked" than it stopped working.

Did that stop me from trying the behavior again? Nope.

Because sometimes, after a long time of not working, the behavior "worked" again. Slapping the keys is the newest technique in my aberrant operant behavior. If there were such a thing as Computer Protective Services, I'd be in jail by now.

As soon as I can get the correct cable, I'll try hooking my computer up to an external monitor and see if I can solve the problem that way. Meanwhile, I look forward to the arrival of my new workhorse and am keeping my fingers crossed that it proves to be a friendly steed.

Postscript: A Note on Experimental Objectivity

I took Experimental Psychology my junior year of college: probably the most labor-intensive college or grad school course I’d ever survived. We did all our experiments the old-fashioned way, with actual subjects and classic equipment. If our subjects took forever to memorize a list of numbers, then so be it, so long as we had our lab reports -- done in the APA style and meticulously referenced -- in to our professor on time. And Dr. K was definitely of the Old School. Trained initially in mathematics, he demanded precision.

The experimenter was objective. He (they were all “he” in those days, even those of us who were women) was an observer, revealed nothing to the subject, paid attention, and translated all that transpired into recorded tic marks and numerals. We replicated the same experiments that generations of psych students had replicated, far removed from the days when they were new and revolutionary research.

Our first experiment recreated B.F. Skinner’s demonstration of operant conditioning. A rat in a “Skinner Box” learned to push a metal bar to receive a nourishing Noyes pellet. I detested Skinner when I was a student -- never, I thought, had I encountered someone so unfeeling, so unaware of the inner workings of human emotion. Decades later I would read his 3-volume autobiography and learn about the man who carved the initials of his beloved into his arm when his love went unrequited. Who wrote his memoirs with a depth of emotion and a sense of humor and wonder that no textbook dared touch. Noyes pellets had been his invention, designed not to just feed rats but to keep them healthy. I might still have areas of disagreement with him, but I was also left with a new respect for him after reading about his life.

Classmate AC and I teamed up, one to call out when a bar was pushed, one to record tic marks. Our subject was a small, warm, white-furred body whom we handled gently with thick gloves. AC immediately named him Baby.

We placed Baby -- er, the Subject -- in his Skinner box. As required for the experiment, the poor thing had been starved for a day; we already felt sorry for him. The experimental lab was in the attic of a large, old building. The lab cubicles were made of plywood painted sky blue.

Baby wandered around his small cage. Raised himself up on his hind legs. Sniffed here, there. Tried to find an opening in the bars. This was torture.

“Press the bar,” AC whispered urgently.

More aimless meandering in a closed space, a hungry tummy sniffing for food. We waited. Waited some more. Tried to be professional about it. Failed miserably.

At some point, seemingly by accident, Baby pressed the bar. A pellet fell out through a shoot. Baby inhaled it. AC and I did everything but whoop. “He did it! Yes!”

We cajoled. We begged. We were hungry, too. The cafeteria wouldn’t serve dinner for too much longer, and we were about to miss ours. “Come on, Baby, you can do it. Press the bar again. Over there -- no, over there. Press the bar....”

And later: “No, you idiot! Not there, there! It’s the bar, stupid -- oh, come on, come on....” A pellet here, a pellet there. We’d spent at least two hours in the lab; I forget how much longer we were there. Eventually something clicked, just as all the replicated experiments and replicated textbooks said it would. Baby put two and two together. He was at the metal bar going pushpushpushpushpush and snatching up the pellets going clinkclinkclinkclinkclink, and AC and I were jumping up and down and screaming GO BABY GO!!!

Dutifully, Experimenter A called out the frequency of metal bar depressions. Experimenter B inscribed the appropriate markings on the lab sheet. The Subject pigged out (er, exhibited the correct operant behavior).

Years later I told the story to my friend L, now retired, whom I then called Dr. B. L had been my advisor, boss, and professor for most of my psych courses. When I visited him in the early 90s, almost 15 years after I'd graduated, the college had done away with the lab and set up its experiments as computer simulations. The attic had been destroyed completely. Pigeons roosted in what was once the observation room, the old furniture of my undergraduate days covered in guano. I related, a little embarrassed, how quite un-objective AC and I had been.

L bristled. “Well of course! They’re not going to get that lesson with the simulations!”

Lesson?

Nobody told me that part of the lesson was that complete objectivity is a myth. That perfection is a Holy Grail. That humans are just that, and that humanity itself can be a confounding factor in scientific research. Dr. K had never breathed such a thing. Nobody told me that someone whose theories sounded to me so cold and authoritarian could show such warmth and vulnerability in his autobiography. It had taken more than a decade since my Experimental Psych days for me to recognize its hidden, "unscientific" agenda.

3 Comments:

When our computers start getting arthritic, oh it's so sad... we've spent many a year in intense dialogue, and now this! I've come to find the hum of my iMac soothing, but I know it won't go on forever! That we could bury our computers out of recognition of their years of service... hope the newly reconditioned one is as good to you!

A black out! I hate when that happens and it did to me not too long ago.

My sister Sherry's last name is Pigeon!

Hey guy's...... So many offers & coupons on baby clothes & apparel are available here at Couponalbum.com from all the major stores..........!!!

Post a Comment

<< Home