Weaving Without A Loom

On the magic of spiders and the wonders of obsession....

Mary called me out to the hedge a few days ago, where she discovered a black-and-yellow argiope. A big one. Simply gorgeous. Body resplendent in geometric black, white, and yellow markings, a Faberge egg in vivo. There's a good description of one here, with more photographic detail than what I was able to shoot.

As a child I was afraid of spiders; as an adult I grew to love them, and more. We haven't yet come across a brown recluse but a black widow lives in the laundry room. Both types are dangerous but they're also shy, so we leave each other alone. Spiders make great natural insecticides -- and, among the widows, only the adult females are poisonous.

The first spider creation myth I read was that of Arachne, thanks to The Greek Gods by Bernard Evslin, Dorothy Evslin, and Ned Hoopes (Scholastic Inc., 1966). Long before I heard of Bulfinch's Mythology, the books by Evslin, Evslin, & Hoopes had fired up my young brain with all sorts of fabulous supernatural fodder. As much as the text, William Hunter's illustrations lent an unforgettable psychedelic grandeur to the deities.

Arachne, young and talented, boasts that she is a better weaver than the goddess Athene (aka Minerva). Athene puts Arachne to the test in a contest. Arachne's work is judged flawless, but she has woven scenes of the gods' follies, which does not help her popularity among the powers that be. By the end of the tale Arachne hangs herself. Seeing the mortal woman dangling from a noose, the goddess Athene transforms Arachne into a spider dangling from its web.

Much as I liked Athene (who along with Artemis gave me strong female role models), I was convinced Arachne had gotten a raw deal. Here was a girl of low birth, who had raised her status through her natural talents and who dared to be impious, a free-thinker. Because of that, and despite the perfection of her craft, she dies. As an eight-year-old girl reading the tale I thought: Not fair!

Dr. Bruce R. Magee summarizes the injustice quite well in his essay, "Minerva's Arachnophobia in Ovid's Metamorphoses":

Arachne commits the unforgiveable sin of telling the truth. Rulers, be they gods or people, like to think that they rule for benevolent reasons and that they are doing the ruled a favor by bringing them civilization, pax, or, in this case, textiles. Confronted with dissidence, they can become quite dangerous. This danger is evident in Minerva's response to Arachne; Minerva is outraged at the success of Arachne, whose tapestry has come out flawless. Minerva lives down to Arachne's portrayal rather than up to her own self-portrayal, proving the truth of Arachne's accusations. She asserts her power at the price of her legitimacy. The reader comes away feeling sympathy for Arachne, not Minerva. Arachne becomes a spider, retaining her isotheistic weaving skills but losing her voice, her ability to narrate through her loom. However, while Minerva could silence the singer, she could not silence the song.

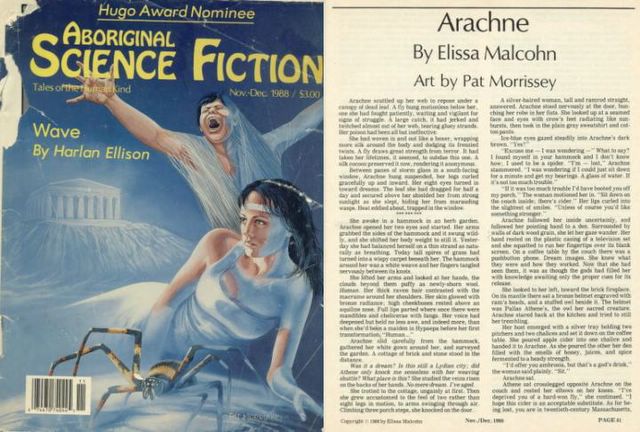

Twenty years after I first read the story of Arachne I got the chance to defend her, in the form of a sequel to the tale. Also titled "Arachne" (published in Aboriginal Science Fiction, December 1988), the story continues the rivalry between mortal and goddess. Pallas Athene brings Arachne -- an argiope in my story, an orb-weaver -- back into human existence but with a spider's sensibilities. This time Arachne must re-weave together an unraveling universe -- a task beyond the powers even of the gods themselves, yet ultimately within Arachne's hybrid grasp. I drafted the story in two days, after some rather unusual "preparation".

In a beautiful instance of serendipity, two articles, both published in November 1986, gave me my inspirational spark. The first was "Spider Madness," by Dava Sobel, in Omni. The second was “Everything’s Now Tied to Strings,” by Gary Taubes, in Discover.

Sometimes writing engages me in my own version of "spider madness." Synchronicities abound when I am obsessed with the work at hand. The universe weaves itself into place. Case in point: the Omni article profiles Peter N. Witt, who at that time had been studying spiders for almost 40 years. The researcher in the Discovery article, who postulated that the universe is made up of infinitesimal strings, is named Edward Witten. The coincidence in their names plastered a big grin on my face.

In addition, a New York Times article had just been published on the theory that the universe is made up of bubbles on a grand scale -- or, as some astronomers alternately put it, knots. I started relating the glue in spider silk to gluons.

As Mary Daly explains in her book Websters' First New Intergalactic Wickedary of the English Language (with Jane Caputi, Harper San Francisco, 1987):

The word webster, according to Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, is derived from the Old English webbestre, meaning female weaver. The Oxford English Dictionary defines webster as "a weaver, as the designation of a woman." According to the Wickedary, Webster means "a woman whose occupation is to Weave, esp. a Weaver of Words and Word-Webs."

(Daly also weighs in on both Arachne and Athene (Athena). In Gyn/Ecology (Beacon Press, 1978), she points to the creative/aggressive component in spiders as beneficial to Spinsters (i.e., those who weave, create). Conversely, Athena is co-opted, swallowed by and then "born" from the head of Zeus, her own true mother forgotten. I was fascinated to read Daly's writings when I finally sat down with her books several years ago.)

Spiders have become totemic for me, and nowhere was that more apparent than during my writing of "Arachne". As a writer I weave stories, finding and working with different patterns. "Arachne" took that obsession to a joyous, quirky, exploratory extreme.

From my notes in 1986:

From Omni: a spider weaves daily,beginning at dawn. The weaving is an obsession; spiders fed will weave daily anyway, ignoring the vibrations of trapped insects in their nets.Vibration in a weave: I thought of the pictorial representation of gravity: a well of cross-strands (space) displaced by weight: stars and planets snared.

An orb-weaver knows beforehand how much silk to use, building her web from the outside-in. Predestination: one "knows" what the finished product will be before one begins. Each web is unique, each spider's pattern similar to and genetically tied to its parents, even though spiderlings have no chance to "learn" their parents' web structures. The knowing is instinctual.

A spider is self-sufficient. She builds her webs alone, living in solitude. If her silk glands are emptied (liquid silk becomes solid through a process yet unknown, before it emerges from spinnerets) while she is young, she will soon build adult-sized webs. Emptying of the glands stimulates them, facilitating web production.

I progressed to Discovery and the Theory of Everything. The researchers postulate that infinitesimal strings take up 9 dimensions of space and one of time. The theory is a marriage between theoretical physics and mainline mathematics, and utilizes the Planck scale (10 trillion times smaller than the atomic scale.) The 6 "unknown" dimensions "remained 10(-33) cm. across" when the universe expanded after the Big Bang, so say the theorists.

Here I have a problem. Theorists are looking at 4 dimensions and wish to reduce the 9 to 4. They cut off their perceptions. What they see as a compressed space may in fact be doorways rather than points. Changing modes of string vibration determine the particles (quarks, electrons, photons, etc.); those particles join or split apart to form the universe. One "nonsense particle," the tachyon, is massless and moves faster than light. Again: nonsense? Or in a different dimension, where the qualities of light/travel/speed are different as well?

Might the Big Bang have been the entrance of matter/web into this universe, from another? (A spinneret is also a portal.) Particles, the article continued, come in gauge fields as well, i.e., packets of energy (photons) that transmit forces (electromagnetism) between particles. Einstein said that gravity warps the universe. Gravity is the force exerted by mass. An insect's mass warps a spider's web.

When a spider spins a web from the outside-in, she knows the size it will take, the outcome. The knowledge, end to beginning, is a fait accompli.

I thought: What would it be like if you had to create the universe anew, knowing its finished form ahead of time? Knowing, instinctually, just how much matter and energy you had with which to weave?

I drew a spider, carved a stamp, played with it as my brain wove strands of story.

I was overcome with the urge to weave and looked in the Yellow Pages. Found Batik & Weaving, located in Arlington, Massachusetts. I called them, got their hours.

I didn't know if I would get a loom, or a hoop, or what. I had no idea what was involved, but I knew to find out what I could. I caught a bus in Harvard Square, got off by Batik & Weaving. Its proprietor was infinitely patient with my incessant questions. Looms run between $100-200. Classes are given at the store/studio on Monday nights. I thumbed through one of the books on sale and found one entitled Weaving Without a Loom.

When I chose a small wooden comb with which to compact the weave, I was handed a needle to make the weaving process go faster.I surveyed the wood posts and boards, wondering how I would construct a loom for myself. I decided that it would wait until I found more information.

"Every so often I have an instinct to do something I've never done before and to wing it," I said with a shy grin. "This is one of those times."

My canvas tote filled with supplies. As I waited for the #77 bus back to Harvard I decided I wanted a hoop: I would weave a web, working from the outside in. I would choose my colors and weave on instinct. I flashed on Lynn Andrews' books, and realized that a circular web-tapestry could also be a shield. How would I get hoops, and work with them? Looms were rectangular. I wanted something where the hoop would remain part of the work. I thought of bicycle tires without the spokes, of hula hoops.

We were coming upon The Caning Shop, and then I knew. I debarked and went inside, where I found wood hoops arranged according to size on pegs.I chose four 12" hoops.

I strung a warp around the first hoop: a spiraling series of knotted lines drawn taut across the diameter. When ready, I gathered the intended wools and began to weave, continuing steadily until 2AM. I looked through the book on weaving and jotted more notes, including a reminder to pick up a copy of Ovid's Metamorphoses and any books I could find on spiders or, better, their webs.

During that sleepless night, November 17 into 18, I wrote the first 3,500 words of "Arachne." I headphoned myself into (and set to play repeatedly) John Adams' composition Shaker Loops, which gave me visions of furious weaving in its own madness of bowed strings.

On November 20 I found, in Time magazine, complementing the New York Times article, a story on superstrings and "bubbles". In early '86 Harvard researchers discovered bubble voids with galaxies on the surface. The universe was seen to be "lumpy" with "clusters of galaxies." At the time of the article, Witten and Ostricker found cosmic strings that are superconductors of electromagnetic radiation. The strings form loops; the loops push dense matter from exploding galactic clusters away, pushing matter into thin shells.

I was past ecstasy. My head was ready to explode.

That night I was at my Harvard job until 6:30 PM to complete a work-related draft. Then I all but ran home and wrote until 2 AM, finishing "Arachne". Hail collided with the window, sheets of freezing rain falling. The wind howled.

Between midnight and 12:30 AM, I stopped writing to gaze admiringly at a translucent yellow spider. It worked its way gracefully across my mirror, to disappear behind the curtains.

"Arachne!" I whispered, thrilled. "Hello."

I grinned at the ceiling.

3 Comments:

What an amazing, delightful and awe-inspiring story. (If you don't turn down the light a little, your brilliance may intimidate me too much to leave comments.) ;)

I dig your research methods.

Do you know Whitman's spider poem?

Till the bridge you will need be formed, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

Wonderful post -- thank you!

Post a Comment

<< Home