The Andromeda Library, interview transcript

Back in 2008 I was interviewed for The Andromeda Library, produced by Final Destiny, and joined producers and hosts Glenda and Tony Finkelstein. You can access the audio at www.glendas-books.com.

The interview was split into two successive shows. I've recombined the components here in their original order -- a general interview followed by a topical interview -- and added hyperlinks. (Continued...)

GLENDA: Welcome to another episode of The Andromeda Library. Over the next few weeks, we want to further explore the connection between science fiction and how it inspires and influences real-life science.

TONY: And how horror allows us the opportunity to peek into the minds of humans that would be monsters, and to face our own primal fears.

GLENDA: How fantasy encompasses the epic battles of good and evil, extending our legends forward into future generations.

TONY: Come with us now for an intimate look into imagination, and discover its power to instill within us both hope and fear through the art of writing.

GLENDA: Hello, everyone, and welcome to The Andromeda Library. We are here recording at Necronomicon in St. Petersburg, Florida, and we have Elissa Malcohn with us today, author of Deviations: Covenant, as well as many other titles and short stories. Elissa, why don't you tell us a little bit about yourself?

ELISSA: Well, first of all, thank you very much for having me on the show.

GLENDA: It's our pleasure.

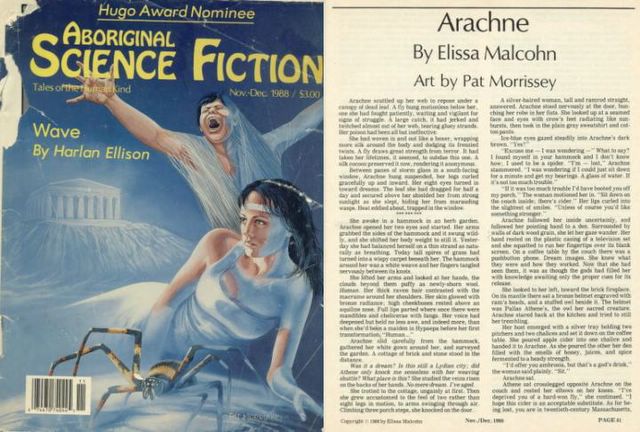

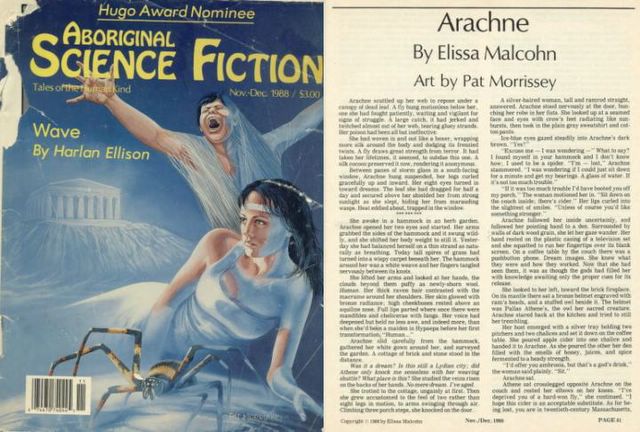

ELISSA: I started writing and submitting at a very young age, started being published in the 1970s in the small press. And then by the time the 80s rolled around, I started being published in magazines like Asimov's, Amazing, Aboriginal Science Fiction, and had a story in the first Full Spectrum anthology out of Bantam Books, Tales of the Unanticipated, so it's been a tremendous ride. My writing fell off during the 1990s and picked up in recent years, and so I'm enjoying a return to this terrific arena.

GLENDA: Very nice. As a writer, what have you found to be some of your most valuable tools that you have acquired along the way?

ELISSA: In very general terms, personal experience, going through life. What I tell my students, because I teach creative writing, is that nothing is wasted. I apply that to myself because for years I was working multiple shifts and was not writing fiction for submission. I had articles published and little pieces here and there. But all the frustrations that I felt of not being able to really get back to my first love -- they became tools in and of themselves, because I was able to get to a certain emotional depth and use that fuel in the writing. And experience that I picked up doing other things. Some of the details in Deviations: Covenant, the transportation system, I used details that I learned while training for and doing the first Boston-New York AIDS Ride in terms of bicycle mechanics. I don't really get into the details in the book, but just little bitty details that I can put in. So, life experience -- in fact, here at Necronomicon, the panel I was on this morning, talking about creating alternative worlds, one of the points I brought up was a transplantation of details. So that you could take detail from everyday, mundane life, and transplant that into fantastic settings.

GLENDA: Very nice. Another interview that I heard you on, you had mentioned about when you started submitting. And you were excited about getting a rejection letter. This is not a typical reaction that a writer has to rejection.

ELISSA: (Laughs) Right.

GLENDA: And if you could just kind of expound upon that, so that writers -- because it is a part of the process when we go to publish. And just the kind of add your little encouraging tidbits as to why you felt so excited about getting a rejection letter.

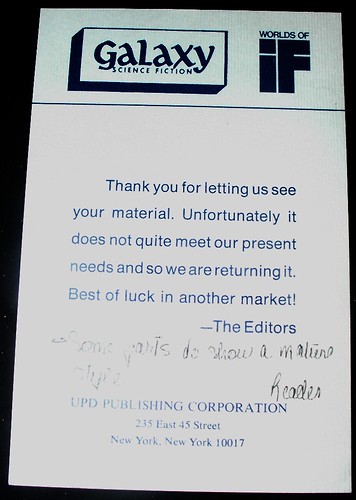

ELISSA: First of all, I was very young. I was barely out of grade school. In 1972 I had taken out my first science fiction magazine subscription, which was to Galaxy magazine, and that's where I got my first rejection slip from.

And these were just little short stories that I had written as a kid. Back in those days, before the Internet, you just sent your stuff out, and I sent mine out slow boat because that was all I could afford on my allowance. And having gotten a rejection slip back at that early an age, as I said in the other interview, I didn't know any better. Which is great, because there's a sense of wonder in there. There's a sense of awe. Here I was making first contact with an editor, with this marvelous world of imaginative grownups that I had been aching to touch. And so for me it was a wonderful experience and nothing but encouraging.

GLENDA: Very nice. Why don't you explain a little bit about what you currently have out on the market for our listeners to acquire and read.

ELISSA: I'll talk about material that came out in 2008. I've got short stories in two, it's soon going to be three issues of a lovely little publication called The Drabbler that Sam's Dot Publishing puts out. The Drabbler is collections of short-short stories called a drabble, meaning stories of exactly 100 words. Each issue is devoted to a particular theme. I just discovered that publication this year and I said this sounds like fun, why don't I try my hand at it? And I found that I enjoyed it, and apparently Terrie Leigh Relf, the editor, liked my stuff enough to accept it and put it in there.

I also have a story called "Hermit Crabs" in issue 14 of Electric Velocipede, a small-press magazine. The magazine itself last year reached the final ballot for a World Fantasy Award.

Update: Electric Velocipede won a Hugo Award in 2009. "Hermit Crabs" is on the recommended reading list in The Year's Best Science Fiction, 26th Annual Edition.

And a reprint of a story of mine, published 20 years ago in Aboriginal Science Fiction, a short story called "Arachne," appears in an anthology called Riffing on Strings: Creative Writing Inspired by String Theory, out from Scriblerus Press.

Update: Riffing on Strings won an IPPY Silver Medal in 2009.

I have a short story called "Memento Mori" forthcoming, slated for release I believe in December, in Unspeakable Horror: From the Shadows of the Closet, an anthology that Dark Scribe Press is putting out.

Update: Unspeakable Horror won a Bram Stoker Award in 2009.

Online people can read me in Helix issue number 10. [URL given is no longer up.] My story in there is called "Prometheus Rebound."

Update: Helix: A Speculative Fiction Quarterly stopped publishing at the end of 2008. You can read a .pdf of "Prometheus Rebound" here.

And of course I have Covenant. That's been out since 2007. And the sequel, Deviations: Appetite, is forthcoming. [Update: You can now download Appetite at the Deviations page and elsewhere.]

GLENDA: Very nice. You said that you also teach creative writing. For our aspiring writers that are listening right now, what are some of the exercises you give your students to develop their skills in writing?

ELISSA: I give a number of exercises, and in fact I'm teaching a couple of workshops next month at the Florida Writers Association conference. One of the workshops I'm giving there is in metaphor. And I encourage my students. I say, "Do not be afraid to sound silly or to stretch believability when you are exercising." Because it's like anything else. It's exercising muscles. Natalie Goldberg has a wonderful quote in her book Writing Down the Bones, which I'll paraphrase here. She goes, "People never think of football teams practicing long hours for a single game that the public may see two hours or so of." [Actual quote: "It is odd that we never question the feasibility of a football team practicing long hours for one game; yet in writing we rarely give ourselves the space for practice."] In writing it's the same way. You put in these long, long hours of practice to really hone your craft. Metaphor is often something that people have difficulty grasping. So I will tell them to come up with vocabulary words of something that they have an interest in, a profession or a hobby, an area they're familiar with. Once they come up with those words, I give them a scene, a particular scene, to write from the point of view of a character who really thinks only in those terms. And so, you end up taking -- one of my students was a lawyer, and so there was all this legal terminology being applied to something that had absolutely nothing to do with the profession, but we were learning to transpose those words and give them new meanings, and using them in a different context. And that's why I tell my students, don't be afraid to go overboard or sound silly when you're practicing. This is exercising muscles that sometimes people don't realize they have.

TONY: So you say that one of your students was a lawyer. Now, do you teach primarily adults, or do you teach in high school and junior high as well?

ELISSA: I teach primarily adults. It's an adult ed course. The first time I taught was actually a course in science fiction writing at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I've taught a course, "Writing From Observation," at the Dorchester Center, also in Massachusetts; and a general "From Muse to Manuscript" course at the Art Center of Citrus County. I've had one student who was, I would say, high school age. But basically my students have been adults. And since it's adult ed, I find myself very lucky in that these are people who want to take the class. They're paying to take the class. So they're motivated.

GLENDA: They really want to be there.

ELISSA: Right.

GLENDA: They really want to get something out of it.

TONY: Not like the ones who say, "Oh my God, here comes another English class," or, "Here comes another English lit," or, "I have to read this." But you have people who are actually motivated to get something from the course.

ELISSA: Exactly. And part of that comes from the fact that my mother had been a high school English teacher in the public school system. It was a love-hate relationship. What she was able to inspire her students to do, and the reward, was tremendous. And so, some days she would come home and say, "Elissa, this is the best job in the world." And other days she would come home and say, "Elissa, this is the -- whatever you do, don't teach! It's the worst job in the world." Because you have those frustrating days, especially when you're working in a public school system. And so, I have that as part of my background, and for me adult ed gives me the best of both worlds.

GLENDA: I really -- I don't want to get too far away from this. You had mentioned about exercising your skills. And a lot of times when authors, especially new writers, are coming in and asking for tips and stuff like that, occasionally I will mention the fact that I have several manuscripts that I have written that will never see the light of day as a published book.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: Mainly because it was my exercise. Because you do pour a lot of time and effort, and a lot of people think that just because you pour time and effort into something, that must be something that must be published. Not necessarily.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: It is during those manuscripts that I was honing my skills of how to interweave character development and plot line and what works best, what doesn't, for me. Because our creative processes are slightly different no matter who you ask. They're going to be -- the creative process as well as the end result, there are still certain facets you go through. The first draft, second draft. The grammatical stuff. All these little pieces are kind of -- but the creative process is very individual.

ELISSA: Yes. I tell people there's no one size fits all, not only between writers, but between and among individual pieces out of a single writer. One of my favorite books on craft is Naomi Epel's The Observation Deck. And it's a fun book. It comes with a deck of cards. You can do all sorts of playing around with it. But she went out and interviewed all sorts of successful authors from all sorts of different genres. They tell her what has worked for them. I tell my students, one of the things I recommend is to carry a notebook everywhere with you. Something that doesn't need batteries. Something that you can just open up, take out a pen -- make sure you have a pen with you -- and write at the spur of the moment. And the type of notebook, well that's whatever you're comfortable with. Some people like a legal pad. Some people like a bound notebook. I tell people to keep experimenting, because it's not going to come out perfect from the get-go, even when you're trying to pick up a tool to practice with.

GLENDA: It's organic. It's like creating a vase with clay, you know. Sometimes you've got to squish it up and start over again.

ELISSA: And sometimes the broken shards can be made into something else.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: When I wasn't writing, and again, this is part of my "nothing is wasted" mentality, when I was not writing I was engaging, to save my creative sanity, in mixed-media art. My landlady had this lovely little piece of pottery that, I forget how it got broken, but it got broken. And she gave me the shards and I made an art piece out of it, and was able to sell the art piece. So you never know when something will come in handy.

GLENDA: Exactly. Elissa, why don't you tell us a little bit about who you are as a person? What things do you enjoy outside of writing?

ELISSA: I was born and grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and afterwards lived for 20 years in the Boston area. So until I moved to Florida, I was an out-and-out city girl. Once I moved down here, I was so pleasantly surprised that I adjusted so quickly to a quasi-rural atmosphere in central Florida. The one thing I had to get used to, even more than the heat and humidity, was driving, because I grew up living on the subway. I didn't get my license until I was 31. I didn't own a car until I was 44. And that was my biggest adjustment moving to Florida. But at the same time, I get such a blast out of, every spring, stepping out, seeing ibises in the back yard. I picked up what I call my first good camera, that has -- it's called a macro lens. It allows you to take extreme close-ups. And I became fascinated with Florida's bug life.

GLENDA: And this from a city girl.

ELISSA: This from a city girl!

TONY: You and my daughter would get along famously. She loves bugs.

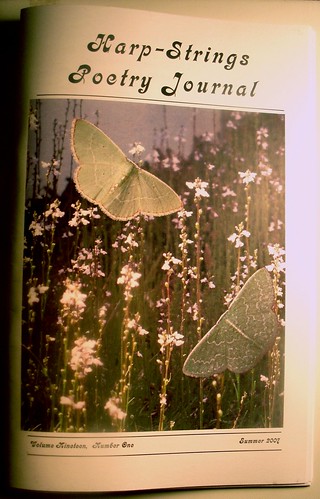

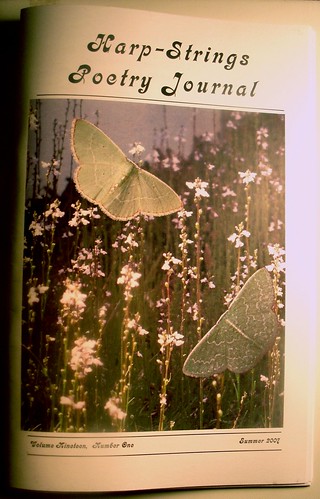

ELISSA: I've heard stories. And to give you another example of how nothing is wasted, one Saturday afternoon in January -- I have a P.O. Box so I walked to my post office, it's a nice one-mile walk from home, and had my camera with me -- and saw a gorgeous Southern Emerald Moth.

It's as beautiful as its name implies. It looks like it was made out of very fine green emerald-colored lace because of the wing markings. And so, it was on the window of the post office, and there I was jockeying for position with my camera. Well, the post office was closed, but the P.O. boxes are open 24/7, and somebody spotted me with my camera taking pictures of government property. And the next thing I knew, I was being approached by a cop who called me over and asked me what I was doing. That incident became part of an article that I wrote for my college's alumni magazine; it was a paying market. It was published last year on bug photography.

And a further use, I took that photo of the Southern Emerald Moth. Not long afterwards I photographed a Red-Fringed Emerald Moth that was on the window of my local Winn-Dixie supermarket.

I put those pictures together --

GLENDA: And no FBI agents showed up with the Winn-Dixie.

ELISSA: No FBI agents showed up --

TONY: We know how important Winn-Dixie is, don't we?

ELISSA: That's right. I had some very pretty pictures of snapdragons in my yard.

Put together a little montage, and that photograph became the cover of I think it was Summer 2007 issue of Harp-Strings Poetry Journal.

So you never know when something will come in handy.

GLENDA: Very nice. I think that's also another lesson that we can learn, too, is the fact that just because you're a writer doesn't mean that you're only gifting is with words.

ELISSA: No, and it shouldn't be.

GLENDA: Yeah. There are so many other things that you can do, that just will add to and actually interconnect and intertwine. Like you said, nothing is wasted that you can use in the craft of writing.

ELISSA: And the more different experiences, the better. I think this is where -- there are a lot of writers out there who have done just about everything Every different kind of job. And that gives you personal experience, and you can then take those details and transplant them.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: It gives you a much richer and fuller experience than sitting alone in a room with your computer, it used to be a typewriter --

GLENDA: Yeah, typewriter, computer, even your tablet. Because I know some writers that even go to the extreme, if they're going to write a sword scene, they go and learn how to fight with a sword. They go take lessons.

TONY: Life knowledge.

ELISSA and GLENDA: Yeah.

GLENDA: Just to add to their own richness of life, as well as being able to expound upon it appropriately within the pages of their book.

ELISSA: Yes. I went out and bought a book on weaving without a loom for a story I wrote that involved weaving. And I was trying to weave in a circular pattern. It was a story that was published in Riffing on Strings, dealing with spiders and spider webs, and I was reading up on orb weavers. And I just started weaving, myself, to kind of get the flavor of it and the feel of what it would mean if this were an obsession. And in a way it's like method acting, but it's method acting in the form of writing.

GLENDA: Very good. If there was a nugget of wisdom that you could leave our listeners with, whether it's during the creative process or during the business end, because there is a business end to writing as well as being creative, what would that be?

ELISSA: I'm going to paraphrase something that I heard, I think it was at Worldcon -- if not, then it was at Readercon -- and I'm not sure if I'm remembering this exactly correctly, and I forget whose law it was ascribed to. Maybe someone out there can call in or let us know. It goes something like this: Ninety percent of people who want to write, don't. Of the ten percent who do, ninety percent never send anything out. Of the ten percent who send something out, ninety percent quit after that first rejection. Of the ten percent who continue to send the material out with patience and perseverance, ninety percent eventually get published. And so, there is that patience and perseverance. Keep at it. Don't get discouraged. That is one nugget of wisdom for the business end of it. And again, what I keep telling everyone I come into contact with, nothing is wasted. No regrets. Use whatever experience you've been able to pick up, good, bad, and indifferent.

GLENDA: Yes. Because many times, it's not the destination. It's the journey.

ELISSA: Exactly.

GLENDA: Well, I want to thank you very much for joining us today, Elissa, here on The Andromeda Library. And I'd like for you to stay on for a topical discussion.

ELISSA: Would love to. Thank you again very much for having me on the show.

TONY: Elissa, thanks a lot.

ELISSA: Thanks. It's been fun.

[Announcements and commercials]

GLENDA: Welcome back to The Andromeda Library. We're going to have a topical discussion here, about human rights, dealing with specifically gender, race, and economics. Joining us is our guest today, Elissa Malcohn. Welcome to our topical discussion today, Elissa.

ELISSA: Thank you very much.

GLENDA: Your book, Deviations: Covenant, actually would be a human rights kind of thing, where race and economics -- I'm not really sure exactly how to describe it, because it's like a ritualistic cannibalism. But both sides kind of struggle within themselves about this Covenant, where one is food for the other, and the other provides the sustenance. It's a very symbiotic relationship, but yet both kind of want to break away from it but feel guilty at the same time for even thinking along those lines, because they've been so intertwined for so many years.

TONY: It must have been written by a Jewish mother.

ELISSA: (Laughs)

TONY: No offense.

ELISSA: My background is Jewish. I know exactly what you're talking about.

GLENDA: Perhaps if you could expound upon those sorts of things.

ELISSA: In the main setting of the first book in the series, you have two societies in the same part of a region. So one other important factor is the environment. This happens to be a very fertile environment, and what that means is that the Masari, who must eat members of the Yata to sustain themselves, in turn sustain the Yata with tithes. They provide the food. They provide the clothing. Because the Yata, having been worshipped as gods and given these tithes, have lost their powers of self-sufficiency. There's that kind of unintentional exploitation going on, but exploitation is what it ends up being, and that's why you have a small population of Yata who want to fight against that -- not only so that their members don't have to go out and be willing sacrifices, but so that they can learn to take care of themselves. It's a system that is hard to fight against if you're used to, number one, being treated and worshipped as a god, but there's that added motivation of, "I don't have to go out and do anything. It's all going to come with me. I just have to trust that the gods won't tell me that this is my day to go."

GLENDA: Exactly.

ELISSA: And that engenders a lot of guilt on the Masari side. The Masari have been raised to believe that they're basically worthless. They're the ones killing and eating the Yata, but at the same time they are the weak ones.

GLENDA: They are living gods and they impart life to the Masari, because without the Yata the Masari will die.

ELISSA: Exactly.

TONY: I have a question. I haven't read the book. If the Yata is a small group and the Masari is a large group --

ELISSA: No. The Yata are small in stature, not small as in population.

TONY: I'm trying to fathom in my mind, if one group is killing off the other group for food, who's left to worship?

ELISSA: Well, this is where a drug called Destiny comes in. In one region, Destiny is used as a sacred aphrodisiac to increase the numbers of Yata. They are able to keep their population up. And part of the reaction against the Covenant is, we're not raising children to be people, we're raising children to be food, depending on what the gods say. But of course, if people have bought into that system, they're saying, "Our children are going to be gods, just as we are." And so it's this internal conflict that occurs. But at the same time, at the other end of the region, which has a whole different economy, a whole different ecology, Destiny is used as a drug to enslave Yata who are raised as livestock. And they are not treated as gods at all. They are treated as basic animals. Part of the conflict in the entire series has to do with these differing philosophies. And there are other areas, other communities, that fall in-between. They have their own forms of exploitation and ways to try to keep a population balanced. Across the region you have characters who are reacting against these different systems and breaking the rules.

GLENDA: Now, in the genre of science fiction and fantasy, these human rights issues play out over and over again. Star Trek was really good with this, dealing with the human rights issues of the time, about racism. Because you had the multiracial bridge crew on the U.S.S. Enterprise, and it was a vision of the future that, yes, we can get beyond our differences and embrace these differences.

TONY: Let's face it, they had the first interracial kiss.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: Yes, which was a big deal at the time that it happened. Science fiction is one of those, because it is a fictional, it is an escapism type of thing, these kinds of issues can be bought out for people to really think on: Is this really a right way to behave or to react to another group, without it being -- challenging their own ideology, I guess is the word I'm looking for. Their own definition of right and wrong, or their own experiences, or if they had a bad experience with this type of individual, so therefore they hate them all.

ELISSA: Right.

GLENDA: And it's kind of like an inoffensive manner, where people can look at both sides of the coin without being immediately on the defensive, to defend their viewpoint.

ELISSA: One of the things science fiction does is, it creates proxies for human beings and the human condition. By using proxies, namely aliens or situations that we generally don't see literally on this planet, science fiction creates a safe atmosphere where loaded topics can be looked at, without having them feel so threatening. In fact, Star Trek was what got me into science fiction as media. When Star Trek went off the air, I missed the show so much that I started writing my own adventures, injecting an alter-ego of my own. And from there I branched out into general science fiction. But when I started really reading science fiction, I immediately gravitated toward a subgenre called New Wave, which was popular during the late 60s and early 70s. It focused specifically on social relevance, on taboo, on inner versus outer space. My writing is very psychological. Hopefully I deal with as much of the science to make that realm believable, because you do need that grounding in something that lends believability to the writing. But my main focus is on the characters, on their relationships with each other, and on the psychology of what a difficult situation does and how the characters deal with that situation.

GLENDA: I think even as far as economics, people have used economics as a reasonability or a rationale to support human rights violations, one in particular being slavery. And I think The Matrix can really touch on that quite a bit and not be offensive to anyone, because truly they reduce the human being to a battery in The Matrix, and it was all about economics. They enslaved the human race. The machines had gotten to this level where they enslaved the human race, who had initially created the machines to make life easier, and it just kind of was this vicious circle.

ELISSA: And what makes it more complicated is that there is a complacency involved.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: You know, you don't have a black-and-white going on here. You have people who really want to live inside this dream because the reality is so grim.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: And so, it also -- it's a very nice self-reflection because it treats the role of escapism.

GLENDA: Yes, it does. Gender is something that has come to light in recent times.

TONY: I just had a thought, though.

GLENDA: What?

TONY: When you're thinking about economics, you had mentioned Star Trek. How Star Trek had gotten you into the science fiction universe.

ELISSA: Yes.

TONY: Star Trek has no economics. No one gets a paycheck, everything is based --

GLENDA: In the original series, no, they didn't. On Next Generation they instituted a credit system, so to speak.

TONY: Right. But they didn't have to buy anything. All they did was walk up to a replicator and make whatever they wanted.

ELISSA: Well, one of the tricks that Star Trek used was that the Earth civilization didn't really have to rely on economics. But these planets that the Enterprise was helping to reform and to help while violating the Prime Directive up and down the wazoo --

GLENDA: That was one thing that always bothered me --

TONY: Yeah, the Prime Directive wasn't so prime.

ELISSA: Right.

GLENDA: The Prime Directive was always being violated right and left. First contact would just violate it right off the chute --

ELISSA: And so your main conflict happened with these non-Earth civilizations, who did have an economic system.

TONY: Because Star Trek's always saying, "There is no poverty. There is no discrimination. There is no, what do you want to do with your life?" Even Picard said, "I didn't want to farm. I wanted to do something else with my life. I wanted to explore the universe." And they find somebody. You could do whatever you want to do. What do you want to do with the rest of your life? Choose an occupation. We're an exploration ship. We don't have to fight. We're here to learn and explore. So there is no economics. Which boils down to, if there is no economics, how do you sustain the planet?

GLENDA: Yeah, do people just -- you know, because --

TONY: Okay, I'm going to farm and give it all away?

ELISSA: Well, that brings up an interesting question. Because what does exist and did exist in Star Trek was, you did have these trades with other star systems. And other, if not Federation members, then planets outside the Federation, which did have economics.

TONY: Yes. Quatrotriticale.

ELISSA: Yes. You do get into issues, either explicit or implicit, of exploitation.

GLENDA: Yes. Well, you also, you just go out and do. There are people who do certain trades and certain things because they have to. This is what their sustenance is. And other people who do it for the sheer joy of doing it.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: In one of the other panels that I had today, we were discussing what makes a good character, and how in good storytelling there must be conflict.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: And what is really strange about humans is that in reality, in our real lives, we strive to do away with conflict. But yet, in a good story, without conflict it's dull, boring, and very mundane. And it's almost like there is this addiction we have to dealing with conflict, but yet we shouldn't want it. And in the Star Trek realm, where they perceive Earth as they're at peace, everything is this little paradise, there is no conflict, and stuff like that -- well, shoot, I want to hop a ship to go find something interesting to do.

ELISSA: Exactly.

GLENDA: We always seek this paradise, but are we really seeking paradise or are we seeking those challenges that make us grow as a person? Are we seeking new knowledge to challenge our concepts of our purpose in this universe?

TONY: Well, that's an age-old question that's never going to get answered.

ELISSA: And as you were saying before, it's the journey.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: So that we might be seeking peace, utter peace. We might be seeking paradise. Every step that we take that moves us closer to that brings us into conflict. It brings us outside our comfort level and it requires us to grow.

GLENDA: Yes, it does.

ELISSA: And so, I think that's why we seek out the challenges that once someone settles down and stops growing, well, that's kind of when you start dying.

GLENDA: Yes, exactly.

ELISSA: And so, we seek out ways to -- in a way, we seek out ways to put ourselves through crap, so that we stay alive.

GLENDA: Exactly. And even farmers, those who farm, who do agriculture, their challenge is nature.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: That is the challenge that they're going against, to get things to grow, to produce a crop. A healthy crop, one that will bring abundance, to bring them other kinds of sustenance, that they are raising these crops in order to trade for equipment or for housing or whatever it is. But that is their challenge. It's not just go out and put a seed in the ground. After you've done gardening, there are all these weeds, all these things that try to keep the good that you instill in the ground from growing. There is a lot to it. So their challenge is not, "I'm just a farmer." No. Their challenge is nature. They go to war with nature.

TONY: That's very true. And we are about to run out of time for our topical discussion. So, Elissa, I want to thank you for taking part in our program today.

ELISSA: Well, thank you very much.

GLENDA: Definitely. I really appreciate you coming.

ELISSA: Thanks. I appreciate you having me on the show.

GLENDA: Thank you.

Elissa Malcohn's Deviations and Other Journeys

Promote Your Page Too

Vol. 1, Deviations: Covenant (2nd Ed.)

Vol. 2, Deviations: Appetite

Vol. 3, Deviations: Destiny

Free downloads at the Deviations website and on Smashwords.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License.

The interview was split into two successive shows. I've recombined the components here in their original order -- a general interview followed by a topical interview -- and added hyperlinks. (Continued...)

GLENDA: Welcome to another episode of The Andromeda Library. Over the next few weeks, we want to further explore the connection between science fiction and how it inspires and influences real-life science.

TONY: And how horror allows us the opportunity to peek into the minds of humans that would be monsters, and to face our own primal fears.

GLENDA: How fantasy encompasses the epic battles of good and evil, extending our legends forward into future generations.

TONY: Come with us now for an intimate look into imagination, and discover its power to instill within us both hope and fear through the art of writing.

GLENDA: Hello, everyone, and welcome to The Andromeda Library. We are here recording at Necronomicon in St. Petersburg, Florida, and we have Elissa Malcohn with us today, author of Deviations: Covenant, as well as many other titles and short stories. Elissa, why don't you tell us a little bit about yourself?

ELISSA: Well, first of all, thank you very much for having me on the show.

GLENDA: It's our pleasure.

ELISSA: I started writing and submitting at a very young age, started being published in the 1970s in the small press. And then by the time the 80s rolled around, I started being published in magazines like Asimov's, Amazing, Aboriginal Science Fiction, and had a story in the first Full Spectrum anthology out of Bantam Books, Tales of the Unanticipated, so it's been a tremendous ride. My writing fell off during the 1990s and picked up in recent years, and so I'm enjoying a return to this terrific arena.

GLENDA: Very nice. As a writer, what have you found to be some of your most valuable tools that you have acquired along the way?

ELISSA: In very general terms, personal experience, going through life. What I tell my students, because I teach creative writing, is that nothing is wasted. I apply that to myself because for years I was working multiple shifts and was not writing fiction for submission. I had articles published and little pieces here and there. But all the frustrations that I felt of not being able to really get back to my first love -- they became tools in and of themselves, because I was able to get to a certain emotional depth and use that fuel in the writing. And experience that I picked up doing other things. Some of the details in Deviations: Covenant, the transportation system, I used details that I learned while training for and doing the first Boston-New York AIDS Ride in terms of bicycle mechanics. I don't really get into the details in the book, but just little bitty details that I can put in. So, life experience -- in fact, here at Necronomicon, the panel I was on this morning, talking about creating alternative worlds, one of the points I brought up was a transplantation of details. So that you could take detail from everyday, mundane life, and transplant that into fantastic settings.

GLENDA: Very nice. Another interview that I heard you on, you had mentioned about when you started submitting. And you were excited about getting a rejection letter. This is not a typical reaction that a writer has to rejection.

ELISSA: (Laughs) Right.

GLENDA: And if you could just kind of expound upon that, so that writers -- because it is a part of the process when we go to publish. And just the kind of add your little encouraging tidbits as to why you felt so excited about getting a rejection letter.

ELISSA: First of all, I was very young. I was barely out of grade school. In 1972 I had taken out my first science fiction magazine subscription, which was to Galaxy magazine, and that's where I got my first rejection slip from.

And these were just little short stories that I had written as a kid. Back in those days, before the Internet, you just sent your stuff out, and I sent mine out slow boat because that was all I could afford on my allowance. And having gotten a rejection slip back at that early an age, as I said in the other interview, I didn't know any better. Which is great, because there's a sense of wonder in there. There's a sense of awe. Here I was making first contact with an editor, with this marvelous world of imaginative grownups that I had been aching to touch. And so for me it was a wonderful experience and nothing but encouraging.

GLENDA: Very nice. Why don't you explain a little bit about what you currently have out on the market for our listeners to acquire and read.

ELISSA: I'll talk about material that came out in 2008. I've got short stories in two, it's soon going to be three issues of a lovely little publication called The Drabbler that Sam's Dot Publishing puts out. The Drabbler is collections of short-short stories called a drabble, meaning stories of exactly 100 words. Each issue is devoted to a particular theme. I just discovered that publication this year and I said this sounds like fun, why don't I try my hand at it? And I found that I enjoyed it, and apparently Terrie Leigh Relf, the editor, liked my stuff enough to accept it and put it in there.

I also have a story called "Hermit Crabs" in issue 14 of Electric Velocipede, a small-press magazine. The magazine itself last year reached the final ballot for a World Fantasy Award.

Update: Electric Velocipede won a Hugo Award in 2009. "Hermit Crabs" is on the recommended reading list in The Year's Best Science Fiction, 26th Annual Edition.

And a reprint of a story of mine, published 20 years ago in Aboriginal Science Fiction, a short story called "Arachne," appears in an anthology called Riffing on Strings: Creative Writing Inspired by String Theory, out from Scriblerus Press.

Update: Riffing on Strings won an IPPY Silver Medal in 2009.

I have a short story called "Memento Mori" forthcoming, slated for release I believe in December, in Unspeakable Horror: From the Shadows of the Closet, an anthology that Dark Scribe Press is putting out.

Update: Unspeakable Horror won a Bram Stoker Award in 2009.

Online people can read me in Helix issue number 10. [URL given is no longer up.] My story in there is called "Prometheus Rebound."

Update: Helix: A Speculative Fiction Quarterly stopped publishing at the end of 2008. You can read a .pdf of "Prometheus Rebound" here.

And of course I have Covenant. That's been out since 2007. And the sequel, Deviations: Appetite, is forthcoming. [Update: You can now download Appetite at the Deviations page and elsewhere.]

GLENDA: Very nice. You said that you also teach creative writing. For our aspiring writers that are listening right now, what are some of the exercises you give your students to develop their skills in writing?

ELISSA: I give a number of exercises, and in fact I'm teaching a couple of workshops next month at the Florida Writers Association conference. One of the workshops I'm giving there is in metaphor. And I encourage my students. I say, "Do not be afraid to sound silly or to stretch believability when you are exercising." Because it's like anything else. It's exercising muscles. Natalie Goldberg has a wonderful quote in her book Writing Down the Bones, which I'll paraphrase here. She goes, "People never think of football teams practicing long hours for a single game that the public may see two hours or so of." [Actual quote: "It is odd that we never question the feasibility of a football team practicing long hours for one game; yet in writing we rarely give ourselves the space for practice."] In writing it's the same way. You put in these long, long hours of practice to really hone your craft. Metaphor is often something that people have difficulty grasping. So I will tell them to come up with vocabulary words of something that they have an interest in, a profession or a hobby, an area they're familiar with. Once they come up with those words, I give them a scene, a particular scene, to write from the point of view of a character who really thinks only in those terms. And so, you end up taking -- one of my students was a lawyer, and so there was all this legal terminology being applied to something that had absolutely nothing to do with the profession, but we were learning to transpose those words and give them new meanings, and using them in a different context. And that's why I tell my students, don't be afraid to go overboard or sound silly when you're practicing. This is exercising muscles that sometimes people don't realize they have.

TONY: So you say that one of your students was a lawyer. Now, do you teach primarily adults, or do you teach in high school and junior high as well?

ELISSA: I teach primarily adults. It's an adult ed course. The first time I taught was actually a course in science fiction writing at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I've taught a course, "Writing From Observation," at the Dorchester Center, also in Massachusetts; and a general "From Muse to Manuscript" course at the Art Center of Citrus County. I've had one student who was, I would say, high school age. But basically my students have been adults. And since it's adult ed, I find myself very lucky in that these are people who want to take the class. They're paying to take the class. So they're motivated.

GLENDA: They really want to be there.

ELISSA: Right.

GLENDA: They really want to get something out of it.

TONY: Not like the ones who say, "Oh my God, here comes another English class," or, "Here comes another English lit," or, "I have to read this." But you have people who are actually motivated to get something from the course.

ELISSA: Exactly. And part of that comes from the fact that my mother had been a high school English teacher in the public school system. It was a love-hate relationship. What she was able to inspire her students to do, and the reward, was tremendous. And so, some days she would come home and say, "Elissa, this is the best job in the world." And other days she would come home and say, "Elissa, this is the -- whatever you do, don't teach! It's the worst job in the world." Because you have those frustrating days, especially when you're working in a public school system. And so, I have that as part of my background, and for me adult ed gives me the best of both worlds.

GLENDA: I really -- I don't want to get too far away from this. You had mentioned about exercising your skills. And a lot of times when authors, especially new writers, are coming in and asking for tips and stuff like that, occasionally I will mention the fact that I have several manuscripts that I have written that will never see the light of day as a published book.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: Mainly because it was my exercise. Because you do pour a lot of time and effort, and a lot of people think that just because you pour time and effort into something, that must be something that must be published. Not necessarily.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: It is during those manuscripts that I was honing my skills of how to interweave character development and plot line and what works best, what doesn't, for me. Because our creative processes are slightly different no matter who you ask. They're going to be -- the creative process as well as the end result, there are still certain facets you go through. The first draft, second draft. The grammatical stuff. All these little pieces are kind of -- but the creative process is very individual.

ELISSA: Yes. I tell people there's no one size fits all, not only between writers, but between and among individual pieces out of a single writer. One of my favorite books on craft is Naomi Epel's The Observation Deck. And it's a fun book. It comes with a deck of cards. You can do all sorts of playing around with it. But she went out and interviewed all sorts of successful authors from all sorts of different genres. They tell her what has worked for them. I tell my students, one of the things I recommend is to carry a notebook everywhere with you. Something that doesn't need batteries. Something that you can just open up, take out a pen -- make sure you have a pen with you -- and write at the spur of the moment. And the type of notebook, well that's whatever you're comfortable with. Some people like a legal pad. Some people like a bound notebook. I tell people to keep experimenting, because it's not going to come out perfect from the get-go, even when you're trying to pick up a tool to practice with.

GLENDA: It's organic. It's like creating a vase with clay, you know. Sometimes you've got to squish it up and start over again.

ELISSA: And sometimes the broken shards can be made into something else.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: When I wasn't writing, and again, this is part of my "nothing is wasted" mentality, when I was not writing I was engaging, to save my creative sanity, in mixed-media art. My landlady had this lovely little piece of pottery that, I forget how it got broken, but it got broken. And she gave me the shards and I made an art piece out of it, and was able to sell the art piece. So you never know when something will come in handy.

GLENDA: Exactly. Elissa, why don't you tell us a little bit about who you are as a person? What things do you enjoy outside of writing?

ELISSA: I was born and grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and afterwards lived for 20 years in the Boston area. So until I moved to Florida, I was an out-and-out city girl. Once I moved down here, I was so pleasantly surprised that I adjusted so quickly to a quasi-rural atmosphere in central Florida. The one thing I had to get used to, even more than the heat and humidity, was driving, because I grew up living on the subway. I didn't get my license until I was 31. I didn't own a car until I was 44. And that was my biggest adjustment moving to Florida. But at the same time, I get such a blast out of, every spring, stepping out, seeing ibises in the back yard. I picked up what I call my first good camera, that has -- it's called a macro lens. It allows you to take extreme close-ups. And I became fascinated with Florida's bug life.

GLENDA: And this from a city girl.

ELISSA: This from a city girl!

TONY: You and my daughter would get along famously. She loves bugs.

ELISSA: I've heard stories. And to give you another example of how nothing is wasted, one Saturday afternoon in January -- I have a P.O. Box so I walked to my post office, it's a nice one-mile walk from home, and had my camera with me -- and saw a gorgeous Southern Emerald Moth.

It's as beautiful as its name implies. It looks like it was made out of very fine green emerald-colored lace because of the wing markings. And so, it was on the window of the post office, and there I was jockeying for position with my camera. Well, the post office was closed, but the P.O. boxes are open 24/7, and somebody spotted me with my camera taking pictures of government property. And the next thing I knew, I was being approached by a cop who called me over and asked me what I was doing. That incident became part of an article that I wrote for my college's alumni magazine; it was a paying market. It was published last year on bug photography.

And a further use, I took that photo of the Southern Emerald Moth. Not long afterwards I photographed a Red-Fringed Emerald Moth that was on the window of my local Winn-Dixie supermarket.

I put those pictures together --

GLENDA: And no FBI agents showed up with the Winn-Dixie.

ELISSA: No FBI agents showed up --

TONY: We know how important Winn-Dixie is, don't we?

ELISSA: That's right. I had some very pretty pictures of snapdragons in my yard.

Put together a little montage, and that photograph became the cover of I think it was Summer 2007 issue of Harp-Strings Poetry Journal.

So you never know when something will come in handy.

GLENDA: Very nice. I think that's also another lesson that we can learn, too, is the fact that just because you're a writer doesn't mean that you're only gifting is with words.

ELISSA: No, and it shouldn't be.

GLENDA: Yeah. There are so many other things that you can do, that just will add to and actually interconnect and intertwine. Like you said, nothing is wasted that you can use in the craft of writing.

ELISSA: And the more different experiences, the better. I think this is where -- there are a lot of writers out there who have done just about everything Every different kind of job. And that gives you personal experience, and you can then take those details and transplant them.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: It gives you a much richer and fuller experience than sitting alone in a room with your computer, it used to be a typewriter --

GLENDA: Yeah, typewriter, computer, even your tablet. Because I know some writers that even go to the extreme, if they're going to write a sword scene, they go and learn how to fight with a sword. They go take lessons.

TONY: Life knowledge.

ELISSA and GLENDA: Yeah.

GLENDA: Just to add to their own richness of life, as well as being able to expound upon it appropriately within the pages of their book.

ELISSA: Yes. I went out and bought a book on weaving without a loom for a story I wrote that involved weaving. And I was trying to weave in a circular pattern. It was a story that was published in Riffing on Strings, dealing with spiders and spider webs, and I was reading up on orb weavers. And I just started weaving, myself, to kind of get the flavor of it and the feel of what it would mean if this were an obsession. And in a way it's like method acting, but it's method acting in the form of writing.

GLENDA: Very good. If there was a nugget of wisdom that you could leave our listeners with, whether it's during the creative process or during the business end, because there is a business end to writing as well as being creative, what would that be?

ELISSA: I'm going to paraphrase something that I heard, I think it was at Worldcon -- if not, then it was at Readercon -- and I'm not sure if I'm remembering this exactly correctly, and I forget whose law it was ascribed to. Maybe someone out there can call in or let us know. It goes something like this: Ninety percent of people who want to write, don't. Of the ten percent who do, ninety percent never send anything out. Of the ten percent who send something out, ninety percent quit after that first rejection. Of the ten percent who continue to send the material out with patience and perseverance, ninety percent eventually get published. And so, there is that patience and perseverance. Keep at it. Don't get discouraged. That is one nugget of wisdom for the business end of it. And again, what I keep telling everyone I come into contact with, nothing is wasted. No regrets. Use whatever experience you've been able to pick up, good, bad, and indifferent.

GLENDA: Yes. Because many times, it's not the destination. It's the journey.

ELISSA: Exactly.

GLENDA: Well, I want to thank you very much for joining us today, Elissa, here on The Andromeda Library. And I'd like for you to stay on for a topical discussion.

ELISSA: Would love to. Thank you again very much for having me on the show.

TONY: Elissa, thanks a lot.

ELISSA: Thanks. It's been fun.

[Announcements and commercials]

GLENDA: Welcome back to The Andromeda Library. We're going to have a topical discussion here, about human rights, dealing with specifically gender, race, and economics. Joining us is our guest today, Elissa Malcohn. Welcome to our topical discussion today, Elissa.

ELISSA: Thank you very much.

GLENDA: Your book, Deviations: Covenant, actually would be a human rights kind of thing, where race and economics -- I'm not really sure exactly how to describe it, because it's like a ritualistic cannibalism. But both sides kind of struggle within themselves about this Covenant, where one is food for the other, and the other provides the sustenance. It's a very symbiotic relationship, but yet both kind of want to break away from it but feel guilty at the same time for even thinking along those lines, because they've been so intertwined for so many years.

TONY: It must have been written by a Jewish mother.

ELISSA: (Laughs)

TONY: No offense.

ELISSA: My background is Jewish. I know exactly what you're talking about.

GLENDA: Perhaps if you could expound upon those sorts of things.

ELISSA: In the main setting of the first book in the series, you have two societies in the same part of a region. So one other important factor is the environment. This happens to be a very fertile environment, and what that means is that the Masari, who must eat members of the Yata to sustain themselves, in turn sustain the Yata with tithes. They provide the food. They provide the clothing. Because the Yata, having been worshipped as gods and given these tithes, have lost their powers of self-sufficiency. There's that kind of unintentional exploitation going on, but exploitation is what it ends up being, and that's why you have a small population of Yata who want to fight against that -- not only so that their members don't have to go out and be willing sacrifices, but so that they can learn to take care of themselves. It's a system that is hard to fight against if you're used to, number one, being treated and worshipped as a god, but there's that added motivation of, "I don't have to go out and do anything. It's all going to come with me. I just have to trust that the gods won't tell me that this is my day to go."

GLENDA: Exactly.

ELISSA: And that engenders a lot of guilt on the Masari side. The Masari have been raised to believe that they're basically worthless. They're the ones killing and eating the Yata, but at the same time they are the weak ones.

GLENDA: They are living gods and they impart life to the Masari, because without the Yata the Masari will die.

ELISSA: Exactly.

TONY: I have a question. I haven't read the book. If the Yata is a small group and the Masari is a large group --

ELISSA: No. The Yata are small in stature, not small as in population.

TONY: I'm trying to fathom in my mind, if one group is killing off the other group for food, who's left to worship?

ELISSA: Well, this is where a drug called Destiny comes in. In one region, Destiny is used as a sacred aphrodisiac to increase the numbers of Yata. They are able to keep their population up. And part of the reaction against the Covenant is, we're not raising children to be people, we're raising children to be food, depending on what the gods say. But of course, if people have bought into that system, they're saying, "Our children are going to be gods, just as we are." And so it's this internal conflict that occurs. But at the same time, at the other end of the region, which has a whole different economy, a whole different ecology, Destiny is used as a drug to enslave Yata who are raised as livestock. And they are not treated as gods at all. They are treated as basic animals. Part of the conflict in the entire series has to do with these differing philosophies. And there are other areas, other communities, that fall in-between. They have their own forms of exploitation and ways to try to keep a population balanced. Across the region you have characters who are reacting against these different systems and breaking the rules.

GLENDA: Now, in the genre of science fiction and fantasy, these human rights issues play out over and over again. Star Trek was really good with this, dealing with the human rights issues of the time, about racism. Because you had the multiracial bridge crew on the U.S.S. Enterprise, and it was a vision of the future that, yes, we can get beyond our differences and embrace these differences.

TONY: Let's face it, they had the first interracial kiss.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: Yes, which was a big deal at the time that it happened. Science fiction is one of those, because it is a fictional, it is an escapism type of thing, these kinds of issues can be bought out for people to really think on: Is this really a right way to behave or to react to another group, without it being -- challenging their own ideology, I guess is the word I'm looking for. Their own definition of right and wrong, or their own experiences, or if they had a bad experience with this type of individual, so therefore they hate them all.

ELISSA: Right.

GLENDA: And it's kind of like an inoffensive manner, where people can look at both sides of the coin without being immediately on the defensive, to defend their viewpoint.

ELISSA: One of the things science fiction does is, it creates proxies for human beings and the human condition. By using proxies, namely aliens or situations that we generally don't see literally on this planet, science fiction creates a safe atmosphere where loaded topics can be looked at, without having them feel so threatening. In fact, Star Trek was what got me into science fiction as media. When Star Trek went off the air, I missed the show so much that I started writing my own adventures, injecting an alter-ego of my own. And from there I branched out into general science fiction. But when I started really reading science fiction, I immediately gravitated toward a subgenre called New Wave, which was popular during the late 60s and early 70s. It focused specifically on social relevance, on taboo, on inner versus outer space. My writing is very psychological. Hopefully I deal with as much of the science to make that realm believable, because you do need that grounding in something that lends believability to the writing. But my main focus is on the characters, on their relationships with each other, and on the psychology of what a difficult situation does and how the characters deal with that situation.

GLENDA: I think even as far as economics, people have used economics as a reasonability or a rationale to support human rights violations, one in particular being slavery. And I think The Matrix can really touch on that quite a bit and not be offensive to anyone, because truly they reduce the human being to a battery in The Matrix, and it was all about economics. They enslaved the human race. The machines had gotten to this level where they enslaved the human race, who had initially created the machines to make life easier, and it just kind of was this vicious circle.

ELISSA: And what makes it more complicated is that there is a complacency involved.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: You know, you don't have a black-and-white going on here. You have people who really want to live inside this dream because the reality is so grim.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: And so, it also -- it's a very nice self-reflection because it treats the role of escapism.

GLENDA: Yes, it does. Gender is something that has come to light in recent times.

TONY: I just had a thought, though.

GLENDA: What?

TONY: When you're thinking about economics, you had mentioned Star Trek. How Star Trek had gotten you into the science fiction universe.

ELISSA: Yes.

TONY: Star Trek has no economics. No one gets a paycheck, everything is based --

GLENDA: In the original series, no, they didn't. On Next Generation they instituted a credit system, so to speak.

TONY: Right. But they didn't have to buy anything. All they did was walk up to a replicator and make whatever they wanted.

ELISSA: Well, one of the tricks that Star Trek used was that the Earth civilization didn't really have to rely on economics. But these planets that the Enterprise was helping to reform and to help while violating the Prime Directive up and down the wazoo --

GLENDA: That was one thing that always bothered me --

TONY: Yeah, the Prime Directive wasn't so prime.

ELISSA: Right.

GLENDA: The Prime Directive was always being violated right and left. First contact would just violate it right off the chute --

ELISSA: And so your main conflict happened with these non-Earth civilizations, who did have an economic system.

TONY: Because Star Trek's always saying, "There is no poverty. There is no discrimination. There is no, what do you want to do with your life?" Even Picard said, "I didn't want to farm. I wanted to do something else with my life. I wanted to explore the universe." And they find somebody. You could do whatever you want to do. What do you want to do with the rest of your life? Choose an occupation. We're an exploration ship. We don't have to fight. We're here to learn and explore. So there is no economics. Which boils down to, if there is no economics, how do you sustain the planet?

GLENDA: Yeah, do people just -- you know, because --

TONY: Okay, I'm going to farm and give it all away?

ELISSA: Well, that brings up an interesting question. Because what does exist and did exist in Star Trek was, you did have these trades with other star systems. And other, if not Federation members, then planets outside the Federation, which did have economics.

TONY: Yes. Quatrotriticale.

ELISSA: Yes. You do get into issues, either explicit or implicit, of exploitation.

GLENDA: Yes. Well, you also, you just go out and do. There are people who do certain trades and certain things because they have to. This is what their sustenance is. And other people who do it for the sheer joy of doing it.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: In one of the other panels that I had today, we were discussing what makes a good character, and how in good storytelling there must be conflict.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: And what is really strange about humans is that in reality, in our real lives, we strive to do away with conflict. But yet, in a good story, without conflict it's dull, boring, and very mundane. And it's almost like there is this addiction we have to dealing with conflict, but yet we shouldn't want it. And in the Star Trek realm, where they perceive Earth as they're at peace, everything is this little paradise, there is no conflict, and stuff like that -- well, shoot, I want to hop a ship to go find something interesting to do.

ELISSA: Exactly.

GLENDA: We always seek this paradise, but are we really seeking paradise or are we seeking those challenges that make us grow as a person? Are we seeking new knowledge to challenge our concepts of our purpose in this universe?

TONY: Well, that's an age-old question that's never going to get answered.

ELISSA: And as you were saying before, it's the journey.

GLENDA: Yes.

ELISSA: So that we might be seeking peace, utter peace. We might be seeking paradise. Every step that we take that moves us closer to that brings us into conflict. It brings us outside our comfort level and it requires us to grow.

GLENDA: Yes, it does.

ELISSA: And so, I think that's why we seek out the challenges that once someone settles down and stops growing, well, that's kind of when you start dying.

GLENDA: Yes, exactly.

ELISSA: And so, we seek out ways to -- in a way, we seek out ways to put ourselves through crap, so that we stay alive.

GLENDA: Exactly. And even farmers, those who farm, who do agriculture, their challenge is nature.

ELISSA: Yes.

GLENDA: That is the challenge that they're going against, to get things to grow, to produce a crop. A healthy crop, one that will bring abundance, to bring them other kinds of sustenance, that they are raising these crops in order to trade for equipment or for housing or whatever it is. But that is their challenge. It's not just go out and put a seed in the ground. After you've done gardening, there are all these weeds, all these things that try to keep the good that you instill in the ground from growing. There is a lot to it. So their challenge is not, "I'm just a farmer." No. Their challenge is nature. They go to war with nature.

TONY: That's very true. And we are about to run out of time for our topical discussion. So, Elissa, I want to thank you for taking part in our program today.

ELISSA: Well, thank you very much.

GLENDA: Definitely. I really appreciate you coming.

ELISSA: Thanks. I appreciate you having me on the show.

GLENDA: Thank you.

Promote Your Page Too

|  |  |

Vol. 2, Deviations: Appetite

Vol. 3, Deviations: Destiny

Free downloads at the Deviations website and on Smashwords.

| Go to Manybooks.net to access Covenant, Appetite, and Destiny in even more formats! |

| Participant, Operation E-Book Drop. (Logo credit: K.A. M'Lady & P.M. Dittman.) |

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home