Still Weaning from CNN

I've been in a bit of a fog -- a happy fog, granted -- but with new work coming in, it's time I got back on the stick. I started writing this entry last week but got sidetracked.

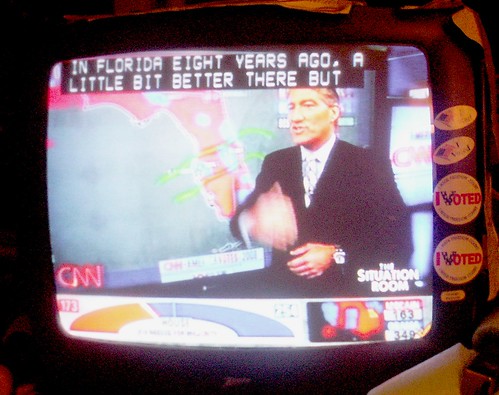

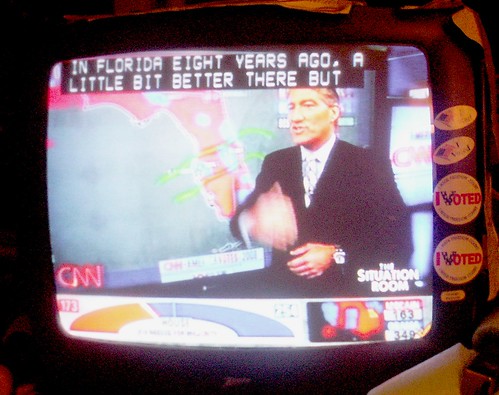

The photo above is my answer to The Kid's meme back on the 4th: "Take a picture of the line you're waiting in, and/or a pic of YOU with your 'I voted!' sticker!!"

Having voted early, I'll let my TV serve as my proxy and Mary's. Note the four "I Voted" stickers to the right of the screen. The large, circular stickers that say "I Made Freedom Count" come from the primary, when we heard our Florida votes were to be tossed out because the primary occurred too early. The smaller, oval stickers up top are from the general election.

I rarely watch TV news, choosing to get my info either from the newspaper or from NPR. That said, when I do watch TV news, it's deep immersion.

I've been listening to and reading the various bits of punditry being bandied about, and on that score there's nothing I can say that hasn't already been said. So instead of doing that, I decided to write about the memories that have traveled through me these past few weeks....

(continued)

The last time I watched the political news this unrelentingly was during the Watergate hearings. I'd literally get home from high school, plop down in front of our dinette's black-and-white set, and be immovable. We had a color TV by then (we'd gotten one in 1966), but the color TV sat in our living room where my father gave piano, organ, and accordion lessons and was inaccessible when students were over. Among other things, the color TV was for late-night, long-before-cable, broadcast news, but our dinette TV was the one most often pressed into service.

That same dinette TV provided my first-ever memory of a presidential election. I was two years old, the year was 1960, and the contest was between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. As the much-later producers of Teletubbies knew, kids pick up on and can remember images from that early, and I was no exception. My single memory, aided by parental reinforcement, was that whenever Nixon's face came on the tube I said, "Shut up, Nixon," no doubt echoing my folks.

I was born during the Eisenhower administration but I remember nothing of it directly. My first political memory dates back to the 1960 debate, the first one in which television made a difference.

I turned 18 less than a month before the 1976 Presidential election. My parents and I went to our polling place, the administration building for Friends Field in Brooklyn. Friends Field was my favorite outdoor hangout, with a picnic table where I spread out my homework and then my writing notebook. I listened to my transistor radio as I daydreamed and watched Little League when a game was in progress. Beyond the baseball field was the F-train's elevated tracks. To the right of that was Washington Cemetery.

This photo dates from the mid-70s. I don't know who this boy was, but I thought it was pretty cool that he had climbed a tree. I'd never been inside the Friends Field administration building before the '76 election. The building is out of frame, off to the right. The F-train "el" is behind me and the cemetery is out of frame, to the left.

For at least a quarter-century I have voted by either punching holes in cards or filling them in on paper sheets (as I did this time). But in '76 I was introduced to levers, in a booth where pulling on a long arm closed and then opened a heavy cloth curtain, the type you'd see in a theater. There was a practice booth for first-time voters, along with a giant replica of the ballot.

The first time I stepped inside one of those for real, armed with the power of my vote, I experienced the best kind of shock and awe imaginable. Pressing down a hard, solid lever with my index finger to vote for my chosen candidate felt like a sacred act. I forget whether I double-checked or triple-checked before I hauled on that massive arm that clicked everything back into place and opened the curtains. I lost track of how long I simply stood inside the machine, taking everything in.

I forget whether I actually heard voices raised and questioning outside, or whether my parents told me afterwards that they had to explain to the others in line that I was casting my very first vote and that's why I was taking so long.

I'd just turned old enough to vote, but I was also old enough to remember Watergate. And, after Watergate, President Gerald Ford's words, "Our long national nightmare is over." His words of hope. I'd voted for Carter, and subsequently wrote him an angry letter when I was protesting against nuclear power after Three Mile Island.

I was only two generations removed from a time when women couldn't vote at all. My maternal grandmother, my only living grandparent when I was born, had attended Margaret Sanger meetings in secret, when birth control was outlawed.

There is much to be said about one's ancestral memory.

I forget how young I was -- somewhere in the early grades -- when I learned about my country's history of slavery, but I remember how utterly shocked I was. My ancestors had fled slavery in Egypt, and I grew up learning that it was one of, if not the most evil institution imaginable. That the country to which I pledged allegiance every school day had engaged in that practice seemed unthinkable, but it was also indisputable.

Closer to home, I'd experienced my first taste of racism in kindergarten. Two teachers ran my class. Mrs. N was a lovely person. Mrs. K berated the only black child in the class, a little girl, telling her over and over how stupid she was and driving her to tears. It's an indelible memory. I was very withdrawn as a child, berated for my almost-constant daydreaming, and I felt powerless to do anything, even to comfort the girl. But I noticed the abuse, and I wish I could have been stronger.

It's probably why I let a black girl beat me up in the schoolyard in the sixth grade. She was convinced, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that I was the same girl who had mistreated her at another school. I had not gone to any other public school. I couldn't convince the girl I was not the person she thought I was, and I suffered only some light bruising. I could see how angry and hurt she was.

My mother taught high school in the inner city and came home daily with stories both horrific and triumphant of what her students experienced. She'd literally broken up knife fights and told me about pot smoke and used syringes in the stairwells. Then there were the students who fought against the odds, her best and brightest, whom she took annually to the Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut. She took me out of my own school for the trips, writing to my teachers that I'd had an upper respiratory infection that day. I enjoyed conversations with her students on the bus and I remember one Magic Moment when one of her students told me she'd held hands with God in a dream. The clasp matched the one I've used in my own spiritual meditations since I was about ten, and it's the same clasp that's the logo for the Boys and Girls Clubs, though I didn't consciously know it at the time:

My mother was also the advisor for the school's literary magazine, and my family's finished basement became the headquarters for cut-and-paste layout. Several students, most of them people of color, spent a day in a neighborhood that was predominantly Jewish and Italian. When I was eight years old my mother pressed me into service to help her grade papers -- first multiple-choice tests against a key, then essays when I knew enough to find grammatical errors. Back then, during the Vietnam War, most of the essays dealt with issues of love and peace and had a simplicity and innocence about them. They contrasted with my mother's reports of prostitutes "doing their business in the teacher's parking lot" and the principal's alleged line to gang members that they could kill anyone they wanted to "as long as it isn't on school property."

She told stories about one student, in and out of mental institutions, who would erupt into screams in the middle of class. After the student had her baby, she fought her demons enough to come back to class to take the final exams needed to get her high school diploma.

Another student, a young man, wrote beautiful nature poetry. One day, when the lock to the teacher's women's room was stuck, he jimmied the door open for my mother. She took one look at his switchblade and asked, "You?" He explained, briefly and sincerely, that he had to survive.

I followed the 1972 campaign of Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, the first major-party African-American candidate for President. I'm happy to see her name mentioned more now than it had been during Jesse Jackson's 1984 and 1988 campaigns, when several sources incorrectly called Jackson the first African-American major-party presidential candidate. He was the second. Shirley was the first. I can hear her voice as I type -- eloquent, civil, and no-nonsense. Still too young to vote, I cheered for her back then, 36 years ago.

When I was in college a friend of mine, L, worked as an usher on Broadway, which meant she traveled through Times Square. She and I belonged to our alma mater's honorary music society. Back in the 70s, Times Square was still a red light district. L was one of the most physically and spiritually beautiful women I'd ever known, who happened to be African-American. She'd been on her way to her job as usher, dressed in a non-provocative way that complemented her beauty, when the cops arrested her for suspected prostitution. I still remember her hurt and outrage.

I also remember her once telling me, "You're very smart, but you're not stuck up about it. You're a real human being." It made me cry, because as much as high grades were valued in my household I was also made to feel ashamed of my intelligence when I was growing up. It makes me cry to remember her kindness and then of how unjustly she was treated.

On the night of November 4, Mary and I sat before the TV with a fresh supply of air-popped popcorn. In addition to CNN, we'd also been on a steady diet of The Daily Show and The Colbert Report, with weekly side trips to Chocolate News. We were watching the John Stewart/Stephen Colbert special on Comedy Central when the election was called for Barack Obama. We toasted the result with sherry before we switched back to CNN.

The photo above is my answer to The Kid's meme back on the 4th: "Take a picture of the line you're waiting in, and/or a pic of YOU with your 'I voted!' sticker!!"

Having voted early, I'll let my TV serve as my proxy and Mary's. Note the four "I Voted" stickers to the right of the screen. The large, circular stickers that say "I Made Freedom Count" come from the primary, when we heard our Florida votes were to be tossed out because the primary occurred too early. The smaller, oval stickers up top are from the general election.

I rarely watch TV news, choosing to get my info either from the newspaper or from NPR. That said, when I do watch TV news, it's deep immersion.

I've been listening to and reading the various bits of punditry being bandied about, and on that score there's nothing I can say that hasn't already been said. So instead of doing that, I decided to write about the memories that have traveled through me these past few weeks....

(continued)

The last time I watched the political news this unrelentingly was during the Watergate hearings. I'd literally get home from high school, plop down in front of our dinette's black-and-white set, and be immovable. We had a color TV by then (we'd gotten one in 1966), but the color TV sat in our living room where my father gave piano, organ, and accordion lessons and was inaccessible when students were over. Among other things, the color TV was for late-night, long-before-cable, broadcast news, but our dinette TV was the one most often pressed into service.

That same dinette TV provided my first-ever memory of a presidential election. I was two years old, the year was 1960, and the contest was between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. As the much-later producers of Teletubbies knew, kids pick up on and can remember images from that early, and I was no exception. My single memory, aided by parental reinforcement, was that whenever Nixon's face came on the tube I said, "Shut up, Nixon," no doubt echoing my folks.

I was born during the Eisenhower administration but I remember nothing of it directly. My first political memory dates back to the 1960 debate, the first one in which television made a difference.

I turned 18 less than a month before the 1976 Presidential election. My parents and I went to our polling place, the administration building for Friends Field in Brooklyn. Friends Field was my favorite outdoor hangout, with a picnic table where I spread out my homework and then my writing notebook. I listened to my transistor radio as I daydreamed and watched Little League when a game was in progress. Beyond the baseball field was the F-train's elevated tracks. To the right of that was Washington Cemetery.

This photo dates from the mid-70s. I don't know who this boy was, but I thought it was pretty cool that he had climbed a tree. I'd never been inside the Friends Field administration building before the '76 election. The building is out of frame, off to the right. The F-train "el" is behind me and the cemetery is out of frame, to the left.

For at least a quarter-century I have voted by either punching holes in cards or filling them in on paper sheets (as I did this time). But in '76 I was introduced to levers, in a booth where pulling on a long arm closed and then opened a heavy cloth curtain, the type you'd see in a theater. There was a practice booth for first-time voters, along with a giant replica of the ballot.

The first time I stepped inside one of those for real, armed with the power of my vote, I experienced the best kind of shock and awe imaginable. Pressing down a hard, solid lever with my index finger to vote for my chosen candidate felt like a sacred act. I forget whether I double-checked or triple-checked before I hauled on that massive arm that clicked everything back into place and opened the curtains. I lost track of how long I simply stood inside the machine, taking everything in.

I forget whether I actually heard voices raised and questioning outside, or whether my parents told me afterwards that they had to explain to the others in line that I was casting my very first vote and that's why I was taking so long.

I'd just turned old enough to vote, but I was also old enough to remember Watergate. And, after Watergate, President Gerald Ford's words, "Our long national nightmare is over." His words of hope. I'd voted for Carter, and subsequently wrote him an angry letter when I was protesting against nuclear power after Three Mile Island.

I was only two generations removed from a time when women couldn't vote at all. My maternal grandmother, my only living grandparent when I was born, had attended Margaret Sanger meetings in secret, when birth control was outlawed.

There is much to be said about one's ancestral memory.

I forget how young I was -- somewhere in the early grades -- when I learned about my country's history of slavery, but I remember how utterly shocked I was. My ancestors had fled slavery in Egypt, and I grew up learning that it was one of, if not the most evil institution imaginable. That the country to which I pledged allegiance every school day had engaged in that practice seemed unthinkable, but it was also indisputable.

Closer to home, I'd experienced my first taste of racism in kindergarten. Two teachers ran my class. Mrs. N was a lovely person. Mrs. K berated the only black child in the class, a little girl, telling her over and over how stupid she was and driving her to tears. It's an indelible memory. I was very withdrawn as a child, berated for my almost-constant daydreaming, and I felt powerless to do anything, even to comfort the girl. But I noticed the abuse, and I wish I could have been stronger.

It's probably why I let a black girl beat me up in the schoolyard in the sixth grade. She was convinced, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that I was the same girl who had mistreated her at another school. I had not gone to any other public school. I couldn't convince the girl I was not the person she thought I was, and I suffered only some light bruising. I could see how angry and hurt she was.

My mother taught high school in the inner city and came home daily with stories both horrific and triumphant of what her students experienced. She'd literally broken up knife fights and told me about pot smoke and used syringes in the stairwells. Then there were the students who fought against the odds, her best and brightest, whom she took annually to the Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut. She took me out of my own school for the trips, writing to my teachers that I'd had an upper respiratory infection that day. I enjoyed conversations with her students on the bus and I remember one Magic Moment when one of her students told me she'd held hands with God in a dream. The clasp matched the one I've used in my own spiritual meditations since I was about ten, and it's the same clasp that's the logo for the Boys and Girls Clubs, though I didn't consciously know it at the time:

My mother was also the advisor for the school's literary magazine, and my family's finished basement became the headquarters for cut-and-paste layout. Several students, most of them people of color, spent a day in a neighborhood that was predominantly Jewish and Italian. When I was eight years old my mother pressed me into service to help her grade papers -- first multiple-choice tests against a key, then essays when I knew enough to find grammatical errors. Back then, during the Vietnam War, most of the essays dealt with issues of love and peace and had a simplicity and innocence about them. They contrasted with my mother's reports of prostitutes "doing their business in the teacher's parking lot" and the principal's alleged line to gang members that they could kill anyone they wanted to "as long as it isn't on school property."

She told stories about one student, in and out of mental institutions, who would erupt into screams in the middle of class. After the student had her baby, she fought her demons enough to come back to class to take the final exams needed to get her high school diploma.

Another student, a young man, wrote beautiful nature poetry. One day, when the lock to the teacher's women's room was stuck, he jimmied the door open for my mother. She took one look at his switchblade and asked, "You?" He explained, briefly and sincerely, that he had to survive.

I followed the 1972 campaign of Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, the first major-party African-American candidate for President. I'm happy to see her name mentioned more now than it had been during Jesse Jackson's 1984 and 1988 campaigns, when several sources incorrectly called Jackson the first African-American major-party presidential candidate. He was the second. Shirley was the first. I can hear her voice as I type -- eloquent, civil, and no-nonsense. Still too young to vote, I cheered for her back then, 36 years ago.

When I was in college a friend of mine, L, worked as an usher on Broadway, which meant she traveled through Times Square. She and I belonged to our alma mater's honorary music society. Back in the 70s, Times Square was still a red light district. L was one of the most physically and spiritually beautiful women I'd ever known, who happened to be African-American. She'd been on her way to her job as usher, dressed in a non-provocative way that complemented her beauty, when the cops arrested her for suspected prostitution. I still remember her hurt and outrage.

I also remember her once telling me, "You're very smart, but you're not stuck up about it. You're a real human being." It made me cry, because as much as high grades were valued in my household I was also made to feel ashamed of my intelligence when I was growing up. It makes me cry to remember her kindness and then of how unjustly she was treated.

On the night of November 4, Mary and I sat before the TV with a fresh supply of air-popped popcorn. In addition to CNN, we'd also been on a steady diet of The Daily Show and The Colbert Report, with weekly side trips to Chocolate News. We were watching the John Stewart/Stephen Colbert special on Comedy Central when the election was called for Barack Obama. We toasted the result with sherry before we switched back to CNN.

| Covenant, the first volume in the Deviations Series, is available from Aisling Press, and from AbeBooks, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Book Territory, Borders, Buecher.ch, Buy.com, BuyAustralian.com, DEAstore, eCampus.com, libreriauniversitaria.it, Libri.de, Loot.co.za, Powell's Books, and Target. The sequel, Appetite, is forthcoming. The Deviations page has additional details. |

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home