Beyond First Impressions

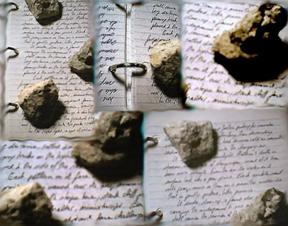

My students and I sit around myriad objects the first day of class. We each meditate on any one of them, writing off-the-cuff long enough to force us to move past the immediate details and start stretching our observation muscles. Long enough to sound weird or silly because all our straightforward material has been used up.

My students and I sit around myriad objects the first day of class. We each meditate on any one of them, writing off-the-cuff long enough to force us to move past the immediate details and start stretching our observation muscles. Long enough to sound weird or silly because all our straightforward material has been used up.That's when the mind opens to new possibilities....

I tell them to keep asking questions:

1. How does the object feel? Does it feel different with my eyes closed? When I squeeze it? When I roll it across my palm? Across my arm?

2. Does it make a sound? What would make it make a sound?

3. How does it smell? From a distance? From close-up?

4. How does it move?

5. How would it look, feel, etc., if I were small enough to walk across it?

6. Is it warm? Cold?

7. Is it hard? Soft?

8. What would it be like in a wind? In a desert? In water?

I do the exercise, too, because the writings are like snowflakes: no two are alike. Even the same object yields different perspectives on different days. I don't remember if I described the same rock or two different ones in the pieces below.

One

It is a boulder, hot against feelers probing for microbes. Uneven ground to walk on, climbing, then descending into crevices. In shadow, heat becomes cold as warmth radiates, then dissipates into the changing air.

It sparkles in the sunlight, flattens and dulls in shadow. Little is left of sharp edges; most of it has been worn smooth. From the air the craters on its surface look like a paw print. Black speckles nest into gray, more so than on a smoother underside that is gently pocked, like pumice.

It exudes, close-up, a faint odor of loam -- carrying the underground to me as surely as a shell carries the sounds of the sea. It has traveled a long distance, rolled down asphalt by the wind of passing trucks on the highway -- buried in snowdrifts plowed to the side of the road.

Each pattern on its face is individual as a fingerprint -- ridges waving over its tiny summit, dropping down a smooth slope here, stark cliff face there. A rock of Gibraltar, miniaturized. Even more so than the cliff, an adjacent face challenges Lilliputian mountaineers, bowing out over the landscape below, threatening to dislodge precarious footing. Easier to take the gradual slope -- scrabbling over rises, digging into the pocks and valleys.

In the right light, a spot of mica flashes like a silver beacon. Light from the sun's glare softens the stone further, makes it appear as though through a matte filter: cinematic subtleties.

Away from the light the cracks expand, make the rock look chapped and struggling to retain moisture, crumbling under harsh, dry winds. Its darkened stipples expand into bruises; it is a survivor. Squeezed, it embeds its hidden message into fingertips, a geologic Braille. The language of the ancients, before the advent of dinosaurs.

Two

The rock folds remind me of elephant wrinkles, and the circle within them the outline of an eye. This would be a white elephant, light shades of gray, linear plane etched into the stone.

It is cool to the touch, hard but not sharp. I can squeeze it in my fist as I would a sponge. It clicks against my ring, seems to stare back at me.

The face I examine looks largely pristine -- a few dark spots but mainly light gray.

The bottom of this mass, a loosely-formed arrowhead, is dirtier. Darker spots, fewer etched lines, more pockmarks; not an elephant but a lunar surface. A pair of pockmarks above a horizontal notch looks like a face peeking out, on the verge of a smile.

The smallest side combines elements of the other two: the semblance of an eye but in a face that looks like it's been beaten to a pulp. Nose and mouth spots fill with rock bearing a yellowish tinge, like putty. But it is as hard and gritty as the rest of the stone.

It has no odor, nothing to indicate organic life.

There is, however, gravity. It weighs down my hand, pulls on my thumb and fingertips, wants to sink back to the center of the earth.

It is an Everest for ants: precarious footing on the slick white wall, footholds on the darker side. But the darker side is steep, almost a cliff, while the slick wall has a gentler grade. Perhaps negotiate the ridge, which flattens out following a merciless, pointed ascent.

The little mountain absorbs heat from my hand. Its crevices fill with the elasticity of my skin, which yields to rigid rock. Any water sluicing over the stone would race away in many tiny streams, diverted by dwarf topography.

Turned on the page, the rock casts differently-shaped shadows. Some almost disappear entirely. The rock rolls with a muted thud, turns with a soft whisper against the paper.

Sightless, I try to read its form, frustrated that my fingertips can discern only so much. Were I to roll the stone on an ink pad, what patterns would it print? What language? Would it leave impressions of imaginary mountain ranges, showing where rivers once ran, gorges collecting runoff? What different pictures would its different sides create? What manner of bird would flock to its cliffs, nest on its ledges? Such birds I think would fly out to sea rather than over a valley; this seems a rock of wind and salt spray, one that has watched the rising or setting sun across an ocean. It does not seem a thing of the landlocked plains. Perhaps the eye that stares at me is the eye of a whale, a petrified Moby Dick, and I scan for a blowhole on the ridge.

2 Comments:

I feel like I had the experience of being in your class as I read this. It is a most stimulating place to be!

I used to say the young students I taught creative writing to...Tell me what it's like, not what it is! I usually got a one word answer!

Post a Comment

<< Home