The Unexpected Trails

I was 31 in May 1990 and had recently gotten my driver's license. After tracking down a magical childhood vacation spot in New Hampshire's White Mountains I had planned to spend time exploring memories. The forest had other ideas....

I was 31 in May 1990 and had recently gotten my driver's license. After tracking down a magical childhood vacation spot in New Hampshire's White Mountains I had planned to spend time exploring memories. The forest had other ideas....May 1, 1990, 7:30 pm. Gilcrest Motel. I have stepped into a time machine and come into the past. Except for ownership (former owner Ted Pritchard died 2 years ago) the place has not changed.

I have unplugged the TV and plugged in the tape deck -- which I had decided to pack, with a selection of tapes -- at the last minute. I moved the lamp from its spot near the door to a spot between the desk -- old, fake-wood formica -- and the bed. Poured myself a glass of Cabernet that I'd opened with the corkscrew on my Swiss Army knife. I dined on chicken, nuts, and sunflower seeds, and coffee.

I am amazed by how much smaller this place appears. When I was last here it was a compact universe; now it is a snapshot. I was an adolescent then. My parents and I had done the touristy things: rides, mini-golf, shuffleboard, horseshoe pitching. Never a real walk through the woods, due largely to my mother's poor health.

On my way here I enjoyed the scenery so much that I missed my exit. I made my way south through Woodstock on Rt. 3 and passed the Jack O'Lantern Motel, which had fascinated me as a child. The Jack O'Lantern features the huge, smiling face of its namesake, whose long arms reach out along its roof from a plaster pumpkin head. The hands seem to hold the motel together. It all looks homemade.

The figure is still there. Still holding onto the motel. Other motels -- cabins, resorts along Rt. 3 -- have also remained. Memory landscapes in vitro.

The Gilcrest's caretaker gave me the key to Room 16 when I checked in. As I looked around the breakfast/game room, he said, "I guess not much has changed."

"No." I smiled. "The last time I was here was almost 17 years ago."

"Wow."

"The Pritchards owned it then."

He nodded. Then he told me about Ted.

I let myself into a room unchanged in many years. Wood walls, stone fireplace, furniture circa 1960. I set out my possessions, looked out the back window toward the Pemigewasett River. There are no phones in the rooms, just a pay phone near the office.

May 3, 1990, 7:39 a.m. A little boy, dressed in bright neon green and pink, in cap, shorts, and jacket, carrying a small lunchbox of the same colors and wearing a blue denim backpack, follows behind a family dog twice his size. The dog sniffs around the grounds near the highway: his "walk" while the boy waits (I suppose) for the school bus. His summer has not yet arrived.

For me, summer in Brooklyn came not on the solstice but when the Wonder Wheel began to turn. To get to high school I rode the IND subway line to Stillwell Avenue -- the Coney Island terminus -- and transferred to the BMT line. Throughout most of the school year the Wonder Wheel remained motionless. Then one day it started turning; I could see from the train the rolling seats slide along their tracks. That was the first sign of summer.

1 p.m., by Sabbaday Brook. I am on a big sitting rock that I believe is off the trail (which seems to have disappeared beneath spring runoff). A small pine grows out of the rock. Roots, strong and gnarled, crisscross everywhere, make me think of Yggdrasil.

I observe the dynamics of water: the constant undulating ripples as it flows around a rock, the drop into a "boiling" pool before a passing current whisks it onward. Sun-washed water, almost gelatinous-looking, magnifying the speckles of a whale-shaped boulder over which it flows; the boulder is a last anchorage for a dead tree whose withered roots snake like ribbons where the rock is dry. Everywhere there are carpets of moss. Beside me a fly sits, studying me; an occasional bee checks out my yellow shirt to see if it is nectar.

(Later) -- I stand on moss off the trail, at what I call the Cathedral of this place. It is cool and shady here, and the brook is quieter. Two jets of water collide, coming at each other from opposite angles.

Four huge branches, almost trees in their own right, arc in a canopy over the brook. They are joined by a tree that emerges from the water's edge by my feet and angles toward the canopy. All are spidery with branches, some of them rising straight up or crooked toward the sky.

At first I wished I had my lap harp, so that I could make an offering of music to the brook and to this place. A harp, however, would not have been suitable for the trek. But I did have my voice. I offered up a wordless, spontaneous melody, singing an offering to the spirits here, however I was moved at the moment. I had wanted to give thanks, and -- as humans often do -- thought of material things. Of course, there was nothing I could give to this place that did not already belong to it. So I gave it a song.

May 4, 1990. I know these roads enough now to enjoy the scenery more, which I do cautiously at these elevations. Yesterday I looked out to the side and saw a memory: the mountains, placed just so. The girl in the back seat of my father's Dodge Demon had taken time out from her reading -- a map or a science fiction novel -- to gaze out the window at those mountains.

The woman sees what the child saw. But the mountains have a new relevance attached to them, through both my own spirituality and Scully's descriptions in The Earth, The Temple, and The Gods. I can see the shapes, the sight lines of mountains anthropomorphised: breasts and nipples, abdomens, pubic clefts, sky-focused plateaus. Larger things than the Old Man of the Mountain or Cannon Rock: visions in themselves but with a different focus. One narrows in on those, constricts the pupils. To view the mountains themselves and their forms in toto, the pupils must dilate. Vision is filled by landscape rather than sighted on a particular object. To drive among these gods in repose -- moving at 65 or 70 mph around elevated curves and gradations -- is akin to flight: not bulleting, but soaring.

On foot, on the trails, it takes me sometimes hours to cover what a car covers in a few short minutes. There, my vision is different: earthbound, even as I ascend. I pick up (sometimes) the human trash of others and carry my own out with me, pay homage to nature. And then I get into the paragon of humanmade machine, emitting exhaust as I soar along a paved highway.

Both experiences are, in their own way, exhilarating.

10:30 a.m. Franconia Falls, off the Wilderness Trail. I am decked out fit for color-shock: bright blue pants, bright yellow shirt. Neon pink cap. Neon green compass wristband. Bright red backpack. Sneakers that are bright orange and gray and sporting mud. A gray woollen sweater, trailing dead leaves, tries unsuccessfully to mute the effect.

The Wilderness Trail, a former railway route, presents a long stretch of old ties down an empty lane bordered by tall birches and pines. At this time of year, whatever will be in summer's full bloom is just beginning to bud, including little, curled "cat's tongue" leaves. I don't know their real names, but they are on stalks and have the roughness of a cat's tongue. They curl at the sides and are green and spade-shaped.

(Later) -- I prepared to make my way over the Black Brook bridge. As I lifted my pack a military aircraft, with what looked like two hulls to either side of the cockpit, buzzed low over the river, emitting a high-pitched roar. I'd heard sonic booms before while walking; at times they can sound like the thunder of the water.

The aircraft startled me, not only by its sudden appearance and the fact that it was military but by how low it was flying. It could not have been more than 20 feet above my line of vision. The contrast between that plane and this place is extraordinary: suddenly, after covering at least five miles with no other human being in sight, I had "company".

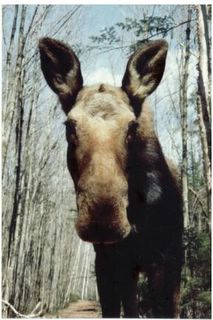

2:53 p.m. For the past ten minutes I have sat several short feet away from a moose. No horns or antlers. A deep, chestnut brown (lighter brown on the back and humped shoulders). Big brown eyes, and white legs from the knees down. She's been chewing her cud and stepping daintily through the shallow pool here. When I saw her I sat down in the middle of the trail.

Her ears are big and furry and she has a very sweet face. We've been watching each other curiously.

She moves closer, now. I write here, "ignore" her to let her know it's okay.

I've been thanking the river whenever I draw water, thanking the trees for support or when their roots provide me with a foothold. Off the trail I very gingerly, when I have to, ease budding branches aside, excusing myself.

I can see how rich and fluffy her coat is. She's been eating well, now about 15 feet away from me. She starts to lunch on one of the ferns. There are plenty of ferns between her and the one three feet from me, although she is coming closer, more like 12 feet away now. It is 3:11.

3:22. One or more of the four boys lying or otherwise resting on the trail has a photo of me on my back, on a bed of dead leaves, and the moose first sniffing at me (her breaths coming one every 1.5 seconds or so, regularly spaced) and then my hand up, patting her nose. A single drop of condensed water fell on my forehead from between her nostrils. Strong sunlight beating down on the right side of my face caused that eye to tear; in the presence of the moose to my left I felt an extraordinary calm.

At what I thought would be her closest approach -- her head filling my viewfinder -- I took my last shot. The camera went into automatic rewind. Whether from that automated, high-pitched sound or from the boys' approach (the oldest is a young man, 16 or 17), she backed off a few feet. I bent over the camera as if to shield it, quietly shushed it and her (turning back): "Shh, it's all right. It's all right. It's okay."

Then I lay back down and she returned, slowly. After we re-established contact, she moved beyond me, toward the boys. Now six more hikers approach, and the boys are motioning for them to sit down, too. The boys snap their fingers at the moose, calling her the way they motion a dog: here, pooch.

She was near the young man when the second group of hikers arrived, startling her into a retreat. He said, "No," in a voice that said, "Please don't go." She turned back.

She is now about 15 feet from me, halfway between me and the boys. Perhaps another 15 feet separates them from the second group. Every few minutes a camera shutter clicks. It is 3:32.

3:40. She inspects the group. The young man who said, "No," stretched out and "napped"; she advanced toward him slowly and sniffed his hiking boots. The boys, who before had been impatient, frowning or stone-faced, now wear smiles as big as mine. I wish I had film left to catch it: she standing calmly in the midst of them all, sniffing another boy's knee before she bounded several steps away, in my direction.

Now she returns to them, sniffs at the head of the "No" man. He looks up at her with an expression of tender awe. He knows he's been blessed, at least honored by her.

The second group moves off (now 3:51). Unless I am watching, I cannot distinguish between footfalls and hoof-falls. Either they have decided not to continue along this trail and to camp somewhere else or they've just moved off to wait. Now the boys, too, move off.

4:05. I stood slowly, put on my backpack, picked up my water-filled Coke can, and said, "Well, sweetie-pie, I'd best be going, too." I took small steps toward the moose, my eyes downcast. She moved back a couple of feet. I stopped, took off my cap, and said, "Now we can say a proper goodbye."

She let me approach. I hardly had to bend for us to touch noses. She, in fact, lowered her head.

I started down the trail. She backed off a foot or two, then turned and trotted several yards ahead of me, stopped and turned around.

I said, "I'm going your way." Pointed.

She trotted a bit more, then stopped. She urinated on the trail. I kept a respectful distance until she was finished and then continued on. We met and touched noses again. I walked past her. "Bye, now. You take care of yourself." I called back over my shoulder. "I'll do the same." Then I added, "Thank you." To her, and to the forest.

Now, hearing a noise behind me, I look back along the trail and there she is again. I have this ludicrous image of her trotting out of the woods, following me. There is now another camper behind her -- I see blue shorts.

(Minutes later) -- My last view was of the new hiker with a camera poised for a shot and the moose staring after me. Now I am far away, the hiker is still seated, and the moose is still staring after me. It is 4:19.

7:00 p.m. The hiker in blue shorts is Sandi, who works for the Appalachian Mountain Club at Pinkham Notch. Very petite and bespectacled, wearing one bandanna around her head and another tied to a frame pack. Red sleeveless shirt, sun-browned arms, black hiking boots. Walking stick. Blonde braid falling halfway down her back.

She started talking about the moose. I told her my story: the four boys, the second group of hikers. She could not establish physical contact, but then started scolding the moose. "You shouldn't be so trusting!" she admonished. "People here are going to come and shoot at you!" She clapped her hands, she told me, yelling at the moose to go away, trying to shoo her off.

Sweetie-pie just stood there and stared at Sandi, then finally moved off the trail.

"How can someone kill a creature like that after they've been that close to it?" Sandi asked me. "I couldn't kill it as is."

"Animals pick up vibes," I said. "One would hope she'd know, when a hunter is out there who would want to shoot her."

The moose, Sandi said, had been the healthiest one she'd ever seen: "Most of them are mangy and thin, with areas of fur missing." We both remarked on this one's radiant, rich coat.

Sandi had just finished two days of camping out. Ironic: these are her two free days after working at a sedentary desk job for the AMC, kept indoors in the midst of wilderness. She books reservations at the Pinkham Notch camp. Her longest hike was six months in duration, when she went with a group from Georgia to Vermont.

She is spending more time hiking and camping out alone, although she does not like to stay in one place for very long, and finding a place where she'd want to pitch her tent for the night is difficult. She's moved spontaneously: packed up her tent, sleeping bag, etc., to leave a place she didn't want to wake up in. Some time ago she had entered a hut that "felt strange" -- no amenities, left in a wrecked condition. "I hightailed it out of there." She had done so struggling with a leg she'd hurt earlier in the day.

"It used to be that if I set goals for myself and couldn't meet them, I thought I failed," she told me. "Now I know -- am learning -- that if I don't reach a place I set out to reach, it's so that something else can happen."

I told her of my experiences: the discovery of Sabbaday Brook Trail and its wonderland after I was unable to reach Tripyramid Mtn. due to runoff. And today: "If I hadn't turned back from the Thoreau Falls Trail, I wouldn't have met the moose."

Sandi had also seen the aircraft -- two of them -- and said she did not think military aircraft were allowed to fly over designated wilderness areas. She, too, couldn't believe how low the planes had been flying. ("One of these days I'll be out here camping and we'll have gotten into a war with someone.") She'd been reclining, at rest, when they had suddenly swooped above her.

May 6, 1990, 11:23 a.m. Porter Square, Cambridge. I've had an early lunch, a salad (first fresh vegetables in six days), while I wait for the supermarket to open. There is an Open 24 Hours sign posted but this is Sunday, and in Massachusetts the Blue Laws are still in effect until noon.

I'd arrived home at 10:30. The morning mountains were spectacular, changing color and perspective as thick cumulus clouds rolled over them.

When I returned my rental car to Budget I was detoured around Harvard Square, which had filled with police barricades and carnival rides. Suddenly we were three lanes squeezing into one and braking for throngs of pedestrians. I took the subway back to the Square, on a train crowded with people wearing bright round stickers in primary colors that spelled out, "Walk For Hunger." That walk had taken place today along with the May Fair: the carnival rides I'd passed.

Harvard Square was wall-to-wall people. And rides; tables filled with store goods; carts with souvlaki, sausage -- a block party multiplied tenfold or more. After a week in the woods I had suddenly stepped into noisy, festive, particolored crowds, the air shimmering with the music of a Peruvian trio playing folk music on a high platform near the Out of Town Newsstand. Children whooped with glee.

"Elissa!" someone called. I glanced back. Sitting in a doorway, enjoying the day, was Hugo, whom I'd first met while working at the University Lutheran Church shelter. I'd been there to volunteer; he'd been there for a place to stay. Now he wore a white painter's cap and sunglasses that reflected me back to myself.

"I didn't recognize you," I said.

He held out his hand. In his palm was a plastic seashell. On the plastic seashell was a smaller plastic seal balancing a ball on its nose.

"A ball on a seal on the half-shell," he intoned. "Sell it to you for five dollars."

I was definitely into the absurdity of the Square. "Sure," I said.

"You're kidding."

"No, I'm not kidding." I laughed, rummaged in my purse.

"You'd buy this for five dollars?" Hugo asked.

"Sure."

"That's bizarre."

"I've been away," I said. "Coming back here to this is bizarre."

I had a ten-spot in my wallet, and three singles.

"Tell you what," I told Hugo, "I'll make a compromise with you. I give you three bucks, you keep the seal on the half-shell, and you can sell it to someone else for ten dollars."

He asked me, "Would you buy it for ten dollars?"

"No, I need that."

"Would you buy it for a hundred dollars?"

"If I find a hundred dollars on the street, I'll give it to you."

(Months ago, Hugo had asked me, when we met, "Do you know what's good about being homeless?" When I said no, he smiled and chirped, "No fixed costs.")

I handed him the three bucks. He thanked me and said, "This'll go toward the down payment on my condo."

I had left the Wilderness and returned to Civilization. It was time to go home.

3 Comments:

Wonderful...The line about the Wonder Wheel choked me up...remembering my own Paragon Park (gone now). Also, the line "the woman sees what the child saw" hit me deeply. I only got half way through...gotta get breakfast and will come back later.

Great yarn; thanks.

Beautiful. I love reading your memories. You really take me there.

Post a Comment

<< Home