Tapir Challenge, Part 4

The Haile 7G fossil dig site is the location of the Florida Museum of Natural History's "Tapir Challenge." More information is on the museum's website.

I spent the day in close contact with this small screwdriver. By the time we finished up around 4:30 PM I was just about as covered as the handle....

Crumbled limestone is shown at lower right.

"You take the area down a little bit at a time, uniformly," our instructor told us. "If you start digging a hole and you find a bone, you can't get it out until you dig it all down. This way you can see the bones laid out if you have an articulated skeleton."

The weather was perfect for a dig. Still, our instructor warned, many people overdo it on their first day of work. Sitting in one position, prying clay, and carrying buckets of dirt around become fairly strenuous. "Take breaks," he advised.

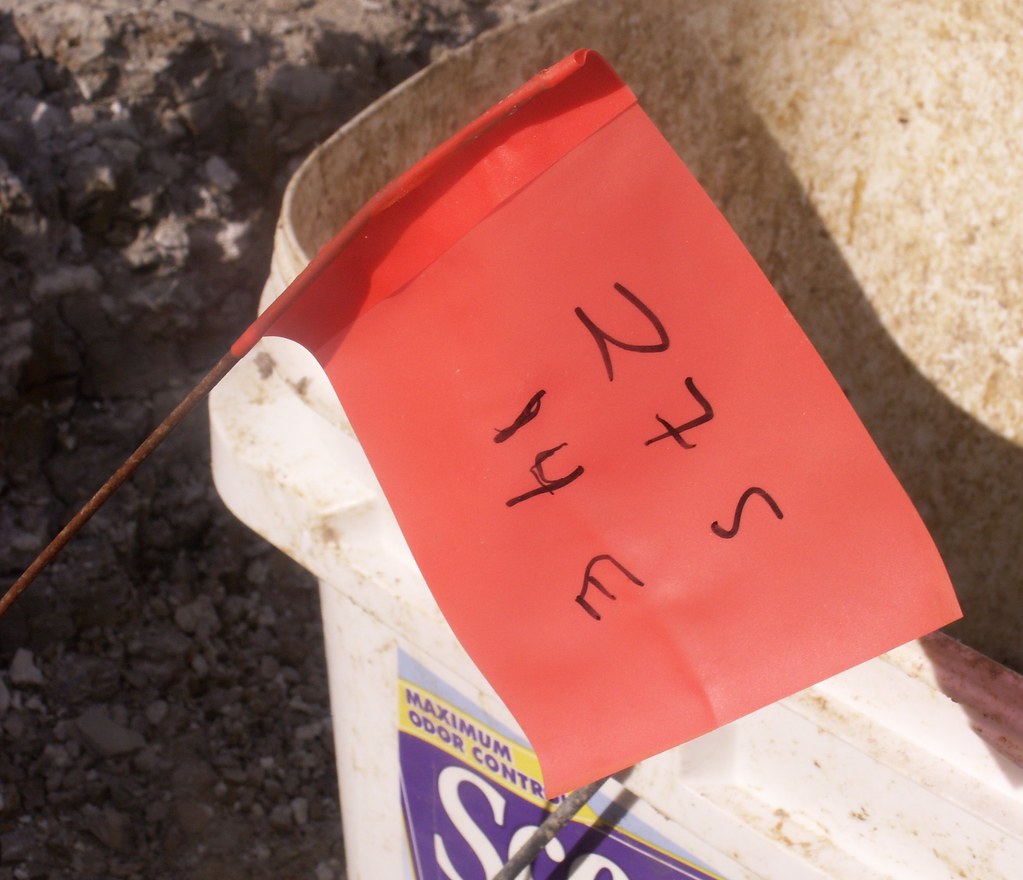

From the supply area we each took a small screwdriver for digging, a trowel for cleaning up, a vial to hold any small fossils we might find, and a plastic bag. We also carried two buckets to our work area, which for each of us consisted of a square meter of mostly clay. Orange flags, like the one shown at upper right, delineated each workspace.

"For skeletons that are fairly complete they're taking a lot of data on the bones," our instructor said. "How far down, what part of the square. For isolated pieces they record the square and you get your name on the label as the collector. It's there forever and ever for someone to study" as part of the permanent museum collection list.

If anyone finds a new species, the new species is usually named after the person who discovered it.

This shot of my workspace includes a sandbag up top.

We worked for the most part in silence, listening to the loud sounds of dredging. Several times during the day the dredging fell silent and we listened to the birds, mostly crows.

We worked in the upper zone. I would move to the lower zone later in the day. "One day this will be the hot spot," our instructor said. "Nothing will be found down there; the next day it's found down there and nothing up here. There are fossils from where we're standing down to the quarry floor."

A "huge jacket" -- a large articulated skeleton, encased in plaster to keep it intact through transport -- had been removed from the upper zone about two weeks earlier. It explained the odd shape of the area where we worked. "Normally we try to keep the squares semi-straight but that's not always possible," our instructor added.

He demonstrated the digging technique, easing his screwdriver through a fine top layer before reaching the clay. We were to dig out the clay, break it up, and throw it into the bucket.

"The limestone will be confusing at first," he said. "Questions will probably be, 'Is this a fossil or a rock?' If it's white, chances are that it will be a rock, but that's not always the case. Teeth can be white." When in doubt, we were to ask. "Rule of thumb for bones is that they're orange-looking or brown. But they'll stand out from the clay because the clay is gray."

This is one of the flags that bordered my workspace in the upper zone. Next to it is my spoil bucket.

Every so often our instructor stopped by and quipped, "Anyone find any skeletons yet?" (At one point he joked he could see four from where he stood, corresponding to the number of volunteers crouched in our small gray alcove.)

One of the volunteers found some tiny fish bones and lizard vertebrae, which I'd have photographed had I been thinking. But my hands were covered in clay dust and grit. The digging itself created a kind of tunnel vision and a devotion to repeated activity: pry the clay, sift through the clay and rocks, dump the clay and rocks into the spoil bucket.

My muscles have recovered from the day, but one side-effect still lingers. The Sunday before the dig I'd watched Guys and Dolls on Turner Classic Movies -- and as I engaged in repetitive digging, sifting, and dumping its music kept playing in my head, particularly the jaunty title song. It lodged in my brain for hours at a stretch and it is still lodged there:

When you see a guy

reach for stars in the sky

You can bet that he's doing it for some doll....

Mary tried to "cure" my condition by singing Edelweiss to me, but it didn't work.

This is my spoil bucket. Spoil consists of clay and rocks that have not yielded fossils. We emptied filled buckets over the edge of the quarry, aiming them away from where the work crew was dredging. (The work crew didn't want to deal with spoil, either.)

Cleaning up our spoil was crucial. If we left the clay in place and anyone stepped on it, it looked as though it had never been dug and would subsequently be dug again.

Remembering how heavy a pile of glossy magazines can be (since a major component of glossies is clay), I lifted my bucket when it was about half-filled and was surprised at how light it was. I probably emptied a filled bucket about a half-dozen times during the day.

I set aside potential fossils that turned out to be rocks. I called the instructor over when I found a brown-black object that turned out to be wood: this was once a forested area. Bones can be "mushy" so I didn't want to take any chances. Another volunteer found an imprint.

Our instructor said, "That's from someone's tennis shoe."

Our instructor works with a couple of graduate students, who had uncovered some turtle, sloth, and other fossils. The fossils, which date from the Pliocene Epoch, are about two million years old.

Update: Writes Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Manager Richard Hulbert on December 8, 2006: "We now know that directly underneath the turtle that Alex was working on was the skull and mandible of a tapir--we collected it today in fact." Graduate students Alex Hastings (orange shirt) and Alejandro Cuellar (black shirt) are joined by Collections Scientist Art Poyer.

They were located behind and below my second work spot. I heard the students discuss teeth coming out of a turtle shell and the finding of a frog hip, interspersed with talk about their plans for winter break.

For the most part, work at the site involved uncovering places where fossils were not present. That in itself is a valuable part of the job. In this shot, my hand is still caked with dried bits of clay from a day's worth of digging. The only fossil I found (and one not relevant to this dig) was the sea urchin spine shown here.

I was holding a relic from the Eocene Epoch.

"The Early Eocene (Ypresian) is thought to have had the highest mean annual temperatures of the entire Cenozoic, with temperatures about 30° C; relatively low temperature gradients from pole to pole; and high precipitation in a world that was essentially ice free," according to the University of California Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley. "Land connections existed between Antarctica and Australia, between North America and Europe through Greenland, and probably between North America and Asia through the Bering Strait. It was an important time of plate boundary rearrangement, in which the patterns of spreading centers and transform faults were changed, causing significant effects on oceanic and atmospheric circulation and temperature."

"You can take that home with you," the instructor said.

I asked, "Is it from the same time period as the rest?"

"No."

"About when does it date from?"

Without blinking an eye he answered, "About 30 to 40 million years ago."

I balked. When I ventured that surely some researcher must want this thing, the instructor gestured toward the wide quarry wall and said, "This place is full of them."

I'm thrilled to have this. I told myself that, after all, my simple act of driving to and from the dig site used a fossil fuel processed from much older stuff.

Still.

I had initially come across the call for dig volunteers while researching trilobites, in an attempt to learn whether Mary had found a trilobite imprint in a rock (shown in this entry) that she'd picked up off the street. When I mentioned the rock to the instructor he said that it was probably not a trilobite imprint -- they're not generally found in our area -- but he suggested that we visit the museum and check with an expert in invertebrate fossils.

The dig is continuing through December 20. I hope to do another stint when it starts up again in the spring. And I think it's time Mary and I planned a trip to Gainesville.

2 Comments:

All these posts, a 'different' type of vacation for sure. And that bone, now what a fabulous memento from a dig. You ache a little, but digging all day, what a rest from everything! How close to the memories of the earth...

Reminds me of digging for old bottles and crystals of which I've done both. I love the treasures that the earth holds. I don't have the eyes for this kind of work though.

Post a Comment

<< Home