"Name one event that changed your life."

Street of impact

In a recent meme I mentioned (but did not choose as my foremost life-changing event) my near-death experience from a car accident when I was seven. "That's an entry for another day," I wrote.

In a recent meme I mentioned (but did not choose as my foremost life-changing event) my near-death experience from a car accident when I was seven. "That's an entry for another day," I wrote.Today's another day....

June 6, 1966 -- Second grade is almost over. I wear shorts, run in the after-school heat after sticks I've shot from an air gun. It is a thick black thing, feels powerful and fun in my hand when I pull the trigger. I load a stick, shoot, take off in pursuit, retrieve.

A black picket fence encloses our front yard, and I have been polishing my climbing skills. The points motivate me to lift myself clear, but my sneaker catches between wooden slats and the picket punches a hole in my shorts. My heart sinks. At the very least my father will yell, tell me how I've pulled another fast one, how I always think I've got everything coming to me.

Earlier in the year I had cried because I accidentally shut a classmate in the coat closet in school, pulling the large wooden doors hard on their tracks. It had been a heinous crime on my part, regardless of the fact that it was an accident. As mortified as I am at my torn shorts, they are nothing compared with trapping a schoolmate in the closet -- even if he was laughing about it afterwards.

The stick blasts from my air gun as I run in my ventilated pants across the street. Back and forth. As my eyes lock with a car barreling down on me the message rings out in my head: "Go to Mom."

I am almost across the street; if I continue in the same direction I can make it to the curb. But Mom is the other way, and I am scared. It doesn't matter that I am closer to the other curb. My instinct turns me around, heads me back the way I came.

In the next moment metal impacts flesh and bone. To this day my body remembers it viscerally each time I cross the street, as though the experience is branded onto my genes. I am unconscious during my flight, though a neighbor says later that she'd seen me thrown a good ten feet into the air. That it was not the metallic punch that sent me flying, but my landing back on earth, that nearly killed me

My mother is bending over me, crying, when I open my eyes. Being in a state of shock lets me be fascinated with the orange blood that pours from my mouth when I turn my head. When I try to get up, vertigo pulls me back down -- but not before I see the bone jutting from my left leg.

I tell my mother, calmly, "I'm going to die."

She sobs, "You're not going to die!"

I know that I will; it is the most obvious thing in the world and I am taking it calmly, because I have no choice. I repeat what I said. She cries out again, almost angrily, "You're not going to die!"

A neighbor tells me that I explained to my mother, "I didn't think I'd be scared before, but I'm scared now." Having dreamt repeatedly when I was a toddler that I was dead, I might well have said this. I don't remember.

In tones of disbelief, my mother tells me later that she and my father had to give written permission before the doctor cut off my $6 pair of shorts. Frankly, I am relieved in the hospital when they take the shears to my clothes. My transgression with the fence goes unnoticed. I will not be punished.

The litany will be repeated many times: two broken legs, the left a compound fracture. Ruptured intestines, almost a ruptured spleen. The beginnings of peritonitis. Two weeks in critical condition, ten in the hospital, four months on crutches afterwards. Small scar below my lower lip, where a tooth broke through.

My stay in Coney Island Hospital had been filled with both magic and horror.

Magic, in that the Coney Island fireworks occurred on Tuesday nights, and the Rockaway Park fireworks occurred on Friday nights, and I could see both from my room. Horror in the unappeasable thirst that wracked me after surgery. I felt it was killing me but I was not allowed to drink.

Instead, I watched the bubbles travel through my nasogastric tube. I was hooked up to food, to blood, to God knew what else. My mother almost fainted the first time she saw me post-op.

Magic in the small transistor radio that my parents brought to the hospital complete with earplug. Frank Sinatra's "Strangers in the Night" was at the top of the charts. And a group called The Cyrcle sang "Red Rubber Ball":

Yes, the worst is over now.

The morning sun is shining like a red rubber ball....

It had a line about starfish in the sea. To my seven-year-old mind the song conjured up the soothing image of a red rubber ball -- in particular, the dark red dodge ball in grade school gym -- floating and bobbing serenely on an endless expanse of deep blue sea.

(I still have that radio, now old and battered. It had been dead for decades. Mary, who is a marvel at making things work, got it to play one day by hooking it to a variety of wires that looked like its own, miniature IVs. Its first, faint sounds came from an oldies station playing songs from the 60s.)

My mother told me my father had wept the day I was taken off the critical list -- that it had been the best Father's Day present he had ever received. I tried to reconcile her news with the fact that as soon as I was off the list my parents brought my schoolbooks to the hospital and placed them on my bed. They wanted me to study and finish out the year while I was still laid up. I insisted -- my right leg in a cast, my left in traction -- that, no, I was not going to study any more that year. I was in the hospital.

They didn't push the matter but they were clearly disappointed. Disappointed, too, when they brought all the get-well notes my second-grade teacher had made the class write, and I refused to write thank-you letters because the girls who were my enemies were lying. Those girls didn't want me to get well, I said. They wrote the notes because the teacher had told them to.

My hair had matted during my weeks in bed; the hospital barber cut off my hair and left the mat. My mother took to my head with a comb and raked out the knots. She told me to stop crying, to stop being a baby.

I knew that Dr. Messina had saved my life, but to me he was an amiable sadist, stopping daily by the foot of my bed to tickle my feet. That in itself was bad enough, but to be restrained in a cast and traction at the time was sheer torture. Fortunately, he stopped as soon as I protested in earnest. I learned later that he was testing to see if I still had feeling there.

(More than 30 years later I called Coney Island Hospital to see if I could get my medical records from that time. But medical records are kept for a decade, not three.)

Daily I had The Three Tests (I didn't think the tickling belonged; it seemed too silly to be a test). My favorite was blood pressure: the way it squeezed my arm, the way the nurse squeezed the rubber ball, the prickling sensation, relief when air whooshed back out. I tolerated the hypodermic blood test by looking away. The finger prick was worst; the sliver of glass slicing into my fingertip always hurt.

I got used to sleeping on my back. From early childhood to this day I prefer sleeping on my stomach, which is hard to do in a cast and traction. My right leg itched from my cast; thereafter its hair grew faster than on my left leg, which partly explains why I stopped shaving my legs early on.

My folks had bought a plastic squeak toy from the Lighthouse, which sold products made by the blind. It was a little plastic dog whose greatest value lay in the fact that I could pull its head off. Pulling heads off dolls was one of my favorite pastimes, but in this case it served a practical use because the head made a great "ball". I'd been moved from intensive care to the children's ward. My roommates and I passed time by tossing the "ball" -- from bed to bed to bed....

Until a throw went wide, and the head fell almost exactly in the middle of the floor, well out of anyone's reach. Our despair did not last long. The windows in the children's ward were made of heavy glass in large wood frames, manipulated with the same kind of brass-hooked pole we used in school. One of the occupied beds was close to the pole. I called for it.

The girl in that bed passed me the pole (across another bed). Somehow, with childhood agility, I maneuvered it around my various equipment. After what seemed forever I poked the hook inside the hollow head and hoisted it high -- several times over the course of our game. My triumph was short-lived when the nurse on duty discovered me in the act.

(More notorious was an adolescent boy admitted the same time I was. He began with half his leg in a cast, and had the habit of traveling by shaking his bed until it moved. By the time I was discharged he was still in the hospital, with a cast that had grown to encase both his legs entirely.)

Most times I was not so popular. Kids, especially kids in pain and laid up for one reason or another, took to throwing at each other objects that were not always as soft as my plastic dog's head. Wooden puzzles, for instance. And they told gross-out stories, like the one about a man on the subway who farted diarrhea.

I don't recall anything being thrown at the six-year-old in the bed opposite mine. Something was wrong with her kidneys. She was generally very quiet, except for those times when visiting hours were over and her grandmother -- the only person to visit her -- had to leave. Then her wailing began, and went on for a good part of the night. I'd like to say I never yelled at her to shut up, as the other children did, but I did yell at her once. She died before I was discharged.

I got my own taste of "shut up" one night, when no amount of painkiller could stop the agony in my left leg and I was screaming at 4 AM.

The hospital gave me my introduction to comic books. I don't know who donated them: Superman, Archie, The Fantasic Four. I loved The Fantastic Four, especially Thing, because of his sense of humor.

When I was feeling better my parents told me that I couldn't keep the comics, or have any at all, and they were returned to their rightful owners. My parents smuggled in pizza every so often, and had bought a small reel-to-reel tape recorder so that I could hear my neighbors' voices and send messages back. Still, the two things I valued most were the comics and my transistor radio.

My move to the children's ward meant I no longer saw the Coney Island and Rockaway Park fireworks, but I could see colors by doing my first paint-by-number picture: a peacock on black velvet. After my father died and Mary and I moved into the house where my parents had lived, I found the peacock hanging on the bathroom wall. It's still there.

Around the time of the painting I had argued with my mother, I forget about what, and received an open-handed slap in the face. When I was in critical condition this same woman had gone to every church and synagogue she could find, asking their congregations to pray that I would live. I started learning early on that human beings are complex.

About a month into my hospitalization, a litter of kittens was born in the back yard and my parents brought me the good news. We had taken to feeding strays, who never came into the house but who knew where the food was; at one time I counted 24 cats and kittens in the yard. The dog next door knew which cats were "ours" and barked only at those who weren't.

At some point the traction came off, and the cast, and I was able to get into a wheelchair. A 14-year-old girl at the end of the ward had a reading problem. She also had Cracked magazine. I wheeled down to her bed, tutored her in reading, and got my comics fix as my reward.

With rare exception I didn't know what the other children were in for. I'd been told about the girl with the kidney problem who had died. A nine-year-old girl lay in a coma, somewhere in the hospital's vast caverns. I never saw her, but we all seemed to know about her. She'd been pinned by a car against a fence and never regained consciousness.

As the saying goes, "Write what you know." Decades later, two of my published stories involved people hospitalized after being hit by a car:

She had seen Dr. Simeon bending over her before he bent over her. Future events were like scraps of memory; all she needed to do was think forward in time and she'd know them. She had forecalled a hit-and-run driver's screech as clearly as the day it happened, felt the shock of metal impacting flesh.______________________________________________________-- from "Moments of Clarity," Full Spectrum (Bantam Books), 1988

"Oh no."

He had expected the worst. Cut wires, contacts shorted, metal torched. But not this.

Not this.

Not a drunk driver swerving out of control, climbing his Chevy over a parked car onto the sidewalk and pinning Donna to the salumeria's stucco wall. Not the tubes that arced in parallel from her nostrils, the needle in her wrist connected to an IV of blood. Donna, sweet Donna who never hurt a soul in her life. Donna, who loved him, who gave him two perfect children, who made him laugh.

-- from "Cog", Tales of the Unanticipated, Fall/Winter 1988.

Coney Island Hospital put me off any desire I'd had for macaroni & cheese. Not because the food was awful, but because one warm summer day I was wheeled outside with my food tray, and a large black spider took an interest in my lunch. It was decades before I could eat macaroni & cheese again, and before I got over my fear of spiders. Before my cast came off I had slept with my enclosed right foot propped up on my bed gate. I once dreamt that a spider, highly magnified, spun its web furiously before me. The dream startled me enough to send my cast crashing down onto the bed, jolting me awake.

My left leg was in worse shape than my right; I had to lose the cast before I could start physical therapy in earnest. At first I was wheeled down to the therapy room; eventually I could get into my wheelchair and take myself to the elevator. I rolled to my favorite waiting area, a wall filled with hand weights. I'd never seen their like before -- they were wonderful, with a solid heft, and felt cool against my palms. Before I knew what I was doing I was performing curls, one arm at a time, and slowly progressing to the next heaviest weight, and the next. It kept me occupied while I waited my turn.

I began therapy by pulling myself along parallel bars to either side of me, putting first a little, then more weight on my right foot. Eventually I would graduate to crutches, but I was already becoming a speed demon in my wheelchair and the staff called to me to slow down.

Physical therapy was the best part of my day. I'd be on crutches for four months following my discharge. Decades after my hospitalization I would be on them again for a torn ankle ligament, and a cop would scold me for loping too fast across a major intersection when the light was with me. (Mary has told me on more than one occasion that I cross the street like a fugitive.) For my part, I was glad to know I still had "the touch."

Once I got the hang of my crutches indoors, I practiced on an outdoor path of large, successive squares of brick, concrete, stone, dirt, and myriad other surfaces. I negotiated my crutches over each, feeling their differences. It was a purely magical experience: colorful, fascinating, and gorgeous. From then on I started visualizing the year in squares along a path. Six months of gray squares from January to June, followed by two months of lush, green squares for summer, and back to four more grays for the fall school term -- up until the end of the road, which was the end of the year. Then a new road would begin.

On August 17 my parents welcomed me home with a color TV in the living room; we'd had only black-and-white prior to that. They hired a private tutor so that I wouldn't have to go to school on crutches. I overheard my father speak disparagingly about the tutor and unwittingly repeated to her what he'd said. He confronted me during my bath: didn't I know I wasn't supposed to say anything? (No.) The tutor had apparently given him a talking-to.

My physical therapy continued, now in the living room. I was to lie on my back, lift and hold up my hips, and pedal my legs as though I were riding a bike. My right leg had no problem with this. My left leg barely bent. Daily I rode my imaginary, upside-down bike. Daily I negotiated what steps I could with my crutches. I slept on the front porch, in a convertible couch, rather than climbed to my bedroom upstairs. I listened in secret to Bruce "Cousin Brucie" Morrow on my radio, in a household where rock was verboten. I watched out the front window as the neighborhood band rehearsed across the street. I managed to fall asleep despite the motorcycle revving around the block, again and again and again.

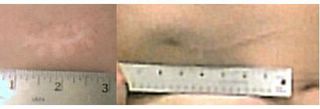

My left leg began to bend more, and more. My right leg, the one with the simple fracture, has no scar from the accident that I can find. My left thigh bears a scar that looks like a cat's paw, where the bone had broken through. When I was anorexic in 1975, the only summer I wore a bikini, I felt no self-consciousness whatsoever about my stomach scar. I cherish those scars. I'd be dead without them.

In 1995 the legs that had bicycled up in the air in my Brooklyn living room pedaled a real bike in the first Boston-New York AIDS Ride. On June 6, 2002 -- 36 years to the day after my car accident -- I ran 3.5 miles in the J.P. Morgan Chase Corporate Challenge in Boston. Later that year my once-broken legs ran the POW-MIA Run/Walk for Freedom 10K.

In 1995 the legs that had bicycled up in the air in my Brooklyn living room pedaled a real bike in the first Boston-New York AIDS Ride. On June 6, 2002 -- 36 years to the day after my car accident -- I ran 3.5 miles in the J.P. Morgan Chase Corporate Challenge in Boston. Later that year my once-broken legs ran the POW-MIA Run/Walk for Freedom 10K.

3 Comments:

I really enjoyed reading this post about your childhood experience. It's funny how we think when we're kids, and you captured that completely. I spent a lot of time in hospitals when I was a kid and even though I dislike them very much, when I'm at one, I feel a sense of nostalgia. Weird.

It brought back hard memories...a sister and a brother both hit by cars, but most especially my son at age 2. At least it had a triumphant ending. (everyone is ok now).

amazing story, and so well written.

Post a Comment

<< Home