Peanuts and Coffee

Taken outside a nearby supermarket. I haven't yet identified these flowers, but several pink, yellow, and white varieties had been planted in the parking lot.

The title refers to my overnight fuel. I'm taking a break from transcribing before I continue on. A fresh pot of coffee (by "pot" I mean the massive, 32-cup variety) sits on the counter. Been juggling the work between meetings and our Hurricane Shutter Quest, since that is this year's main home improvement project. At least, that's the plan.

Meanwhile, the denizens of spring are out in full force....

Hello, Young Lubber (with apologies to Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein)

Romalea guttata (sometimes called Romalea microptera), Family Romaleidae. The Eastern Lubber Grasshopper was my introduction to Florida wildlife when we moved here 3 years ago. I'd exclaimed to Mary, "We've got black grasshoppers with racing stripes in the yard!" I think the ones I'd seen had yellow stripes at the time, but juvenile lubbers can have yellow or red stripes.

Says the University of Florida, "The lubber is surely the most distinctive grasshopper species within the southeastern United States. It is well known both for its size and its unique coloration. The wings offer little help with mobility for they are rarely more than half the length of the abdomen. This species is incapable of flight and can jump only short distances. Mostly the lubber is quite clumsy and slow in movement and travels by walking and crawling feebly over the substrate....The immature eastern lubber grasshopper differs dramatically in appearance from the adults. Nymphs (immature grasshoppers) typically are completely black with one or more distinctive yellow stripes. The front legs and sides of the head are often red."

Indeed, as commented on Bugguide.Net following Hannah Nendick-Mason's photo, juvenile lubbers are usually referred to by their yellow stripe. But, says Bugguide's info page, "Juvenile (nymph) is black with yellow (or red) stripes, also distinctive."

The little one shown here is, I estimate, about a half-inch long; the adults are considerably larger. When I first saw those I couldn't get over how psychedelic their carapace is. I hope to catch one on pixel later on, but Patrick Coin has a good shot of an adult on Bugguide. (The ones I've seen also have green and purple coloration in spots.)

I was very happy to see this earthworm (Genus Lumbricus, Family Lumbricidae), and happier still to move it from the road to a neighbor's lawn before it got flattened by either a tire or a shoe. These guys (well, guys/gals; they're hermaphrodites) are decomposers par excellence and are wonderful for keeping the soil fertile. I learned to truly appreciate them when I tended my first community garden plot in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Small brain. Five hearts. (Source: EdHelper.com)

I love how the University of California, Davis rhapsodizes about these critters: "The humble earthworm: memento mori extraordinaire: 'Remember that thou shalt die.' The Conqueror Worm, devourer of prince and peasant. Metaphor for the frailty of the flesh, subverter of monuments, leveler of empires. Emblem of the vanity, the evanescence, and the end of all human endeavour. And yet, paradoxically, this earthworm, this great destroyer, is also a great builder- a builder of fertile topsoil, itself the sustainer of all civilization."

Write Matthew Werner, UC Santa Cruz Agroecology Program along with Robert L. Bugg, Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program, in their article, Earthworms: Renewers of Agroecosystems: "More recent studies show that earthworms can help reduce soil compaction, improving permeability and aeration. Earthworms do this through burrowing activities, ingestion of soil along with plant debris, and subsequent excretion of casts. Upon drying, these casts form water-stable soil aggregates. These aggregates are clumps of soil particles bound together by organic compounds, and their presence helps improve soil structure, retain nutrients that might otherwise be leached, and reduce the threat of erosion. "

According to EdHelper, the reddish band on an earthworm is called the clitellum, which occurs closer to the head -- and in fact the head is the more tapered end of the worm. "When two earthworms huddle together with their heads pointing to different directions, they fertilize each other's eggs. While the mating takes place, earthworms use their clitellum to secrete a cocoon to protect their fertilized eggs. Later on, they deposit the egg case in the soil and leave it unattended. Baby earthworms hatch after several weeks."

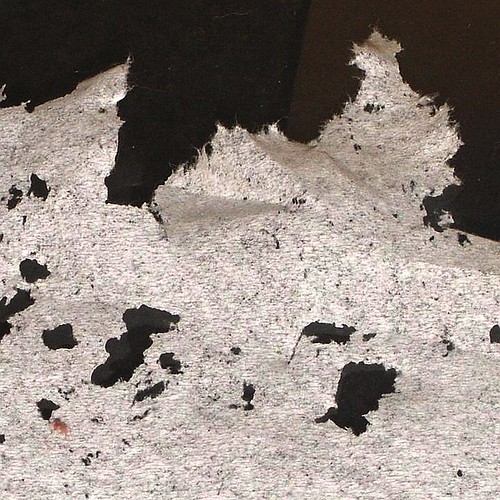

Mary had left a roll of toilet paper in the garage for mopping up oil and any other automotive fluids that found their way onto the concrete floor. Most likely silverfish or pill bugs have chowed down on this outer layer. When Mary discovered the holes, she brought a strip of the paper into the studio for me to photograph.

Palamedes Swallowtail -- Papilio palamedes, Family Papilionidae. Renamed Pterourus palamedes as of 2005 (Marc C. Minno, Jerry F. Butler, and Donald W. Hall, Florida Butterfly Caterpillars And Their Host Plants, University Press Florida, 2005). "Flutters wings constantly," says Bugguide. Through 52 shots this one was having Nervous Wing Syndrome, even when stopping to sip at a lantana blossom. But it hung around the lantana patch for several minutes in all its gigantic glory. It didn't seem to mind that I was following it around, squeezing off shots and mentally grumbling at it to settle down and chill out.

This butterfly is one of the largest I've seen, with a wingspan of around 5 inches (11-13 cm). It ranges through the southeastern United States, extending into central Mexico. Its season spans from March through December in the northern part of that range (2 flights), with a third flight in the southern part of its US range.

Says Bugguide, "Adults take nectar from a variety of sources. Favorites include thistles, native Azaleas, such as Rhododendron atlanticum, and Sweet Pepperbush, Clethra alnifolia." Watching it, I could swear it also guzzles double espresso.

Ichneumon Wasp, Family Ichneumonidae. I'd say this was a Red-tailed Ichneumon (Scambus hispae), except that our Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects and Spiders gives its range as California to Alaska and says adults are active in August. (Then again, I've been informed that this particular field guide has a variety of flaws.) This photo joins several others on Bugguide's page devoted to Ichneumon Wasps, "black with red abdomen" and otherwise unidentified according to species.

This is a beneficial, generally non-stinging family of wasps. Says our field guide, "The larvae are parasites of a wide variety of other insects and spiders and are important in controlling insect populations."

Honey bee (Apis mellifera, Family Apidae). This is a female worker with a pretty full pollen basket on her hind tibia. When she gets home to the hive, she'll secrete a white paste called royal jelly. She'll feed that to the queen, along with collecting, producing, and distributing honey and maintaining the hive along with her 60,000 to 80,000 equally-sterile sisters.

"Complex social behavior centers on maintaining queen for full lifespan, usually 2 or 3 years, sometimes up to 5," says our field guide. "Workers feed royal jelly to queen continuously and to all larvae for first 3 days; then only queen larvae continue eating royal jelly while other larvae are fed bee bread, a mixture of honey and pollen. By passing food mixed with saliva to one another, members of hive have chemical bond. New queens are produced in late spring and early summer; old queen then departs with a swarm of workers to found new colony. About a day later the first new queen emerges, kills other new queens, and sets out for a few days of orientation flights. In 3-16 days queen again leaves hive to mate, sometimes mating with several drones before returning to hive. Drones die after mating; unmated drones are denied food and die."

This worker was gathering pollen from the same lantana patch where I'd seen the prior two critters. Brought by settlers, the honey bee has been in North America since the 17th century.

I think this is a carpenter ant (which would likely make it Camponotus floridanus or Camponotus tortuganus, Family Formicidae), but am not sure. This one and its buddies were hanging out on the roof of my car last night, and this area is in the middle of a swarm. Given the more tapered abdomen and the smaller head, I believe this is either a different species or a different sex (or both) than the ants I photographed the day before, closer to home. Based on the University of Florida description, my guess is that this is a male reproductive. UF says the ants swarm April through June, so this one is right on time. "The peak foraging hours are just before sunset until two hours after sunset, then again around dawn."

"Fondness for sweets" is additional evidence -- I estimate well over 100 covered the window of our local bakery.

According to UF, "During the flight season, carpenter ants can often be found in alarming numbers. Sometimes homeowners are concerned about damage to the structural integrity of their homes, which they sometimes incorrectly learn, is caused by Florida carpenter ants. However, unlike the wood-damaging black carpenter ant, Camponotus pennsylvanicus, found in Florida's panhandle and a few other western U.S. species, Florida carpenter ants seek either existing voids in which to nest or excavate only soft materials such as rotten or pithy wood and Styrofoam. Other concerns are that these ants sting (they do not) and bite (they do)."

"What is she doing?"

I didn't see who shouted the question at around 9 PM from the safety of the strip mall's sidewalk. I raised my head and called back, "Photographing a mole cricket!"

Mary and I had just come from a meeting and had stopped to get a late dinner. It was dark. Mary had seen the mole cricket first, hanging out in the middle of the parking lot. It scuttled away when she tried to coax it into her hand to move to a safer location. I whipped out my camera, popped up the flash, and got down on the asphalt, my butt pointed skyward. Mary stood guard to make sure neither the cricket nor I became roadkill.

Mary has been my Mole Cricket Finder. She'd spotted one on Wednesday at the "post office pond," at around 7:30 PM. That one had moved so fast that the best I could get was a blur. Also, I wasn't using flash.

I believe this is a Tawny Mole Cricket (Scapteriscus vicinus, Family Gryllotalpidae). It's a close call between this and the Southern Mole Cricket (Scapteriscus borellii), but UF does a great job of distinguishing between the two. What decided me were the markings on this one's pronotum -- the helmet-like top of the cricket's head. UF's pronotum guide was a great help here.

Another reason I believe this is a tawny rather than a southern mole cricket is because the southern species plays dead during attempted capture, which this one did not.

Says UF in its description, "The tawny mole cricket is originally from southern South America and arrived in Florida and Georgia about 1900 spreading north and west. It occurs in all the southeastern states, but not, so far, in Puerto Rico or the Virgin Islands. It is currently found in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas."

Right now females are laying eggs in underground chambers, which they will do through June. Each egg clutch contains 24 to 60 eggs, and if a female lives long enough she can lay several clutches. In May and June most of the parental crickets die off. The nymphs are at first cannibalistic; the survivors then feed on plant roots. They begin to reach adulthood in September and breed the following spring.

"The presence of adult tawny mole crickets is most obvious during their springtime flights," says UF. "In Florida, these flights are in February-April and they begin and end several weeks earlier in the south than in the north." Their flights begin soon after sunset and end after little more than an hour. "The tawny mole cricket is a major pest of vegetable seedlings, turf and pasture grasses. Tawny mole crickets feed largely on plant material, and only to a slight extent on insects and other animals."

Based on the info on UF's biology page, I'm assuming this one is a male because of its wing markings. Each mole cricket species uses its wings to "sing" as well as to fly, and only the males sing. Their hearing organs are located on the stubby forelegs they use for digging. This one's left foreleg is positioned alongside its head.

Tomorrow is a work day, though I intend to take some walking breaks. Sunday we've got a matinee at the local community theater, where I have 4 photos on display (that makes 6 photos up altogether). Meanwhile, we're getting the precursors of our summer heat, highs flirting with 90. Today was a "shop towel day," which means that my fingertips were sweaty enough to need the traction of a shop towel in order to pull up my car door button. Eventually I'll get the A/C revived, but so far I've had no problem using open windows and my air vents. And the towel.

3 Comments:

After reading your post yesterday I ran into my daughter's room and woke her, saying, "Do you know an earthworm has a small brain and five hearts? "Umm, yeah, Mom..." was the drowsy reply. When asked later in the day, she remembered me coming in and euphorically saying, 'No work today, I'm home!' but only that she'd dreamt of earthworms.

:)

In another day and age you might have worked on a nature journal, gluing in flowers and insects... the digital version not as tactile, but easier to share.

Luscious first photo. I see what you mean about marking the season by bugs rather than blooms! You must have a great camera.

I have started writing a blog as a class assignment and your blog hase been very helpful in my search for information and guidance for direction in writing my own. I look forward to reading more of your posts. Thank you.

my blog is http://pinolafl.blogspot.com

Post a Comment

<< Home